Briggs soon decided he didn't need more school. He was making good money from Collier's imitating the popular artists of the day. But after a couple of years Briggs realized that he was faking it. Many of his lines were just random squiggles with little understanding of what went on beneath the surface. He was borrowing solutions he hadn't earned, and his shortcuts began to betray him.

His assignments started to dry up. He'd never learned to paint. Desperate for money, he quit the field of illustration. He took other jobs, but all the while he was determined to go back and do it right: "I set about learning to draw, which I never could do before."

Briggs' son described this turning point in his father's life:

I see how correct he was in his mature assessment of his early work: he could not really draw, but with sheer vitality he faked his way to renderings that conveyed power and authority. When the new demand for color illustration left my father in the Depression virtually without work and with a wife and two small children to support, he would not quit. Taking his easel and sketch pad out of the studio, he began to look at the world-- to really see it. Over God knows how many long hours of work, he taught himself until he eventually developed great skill as a colorist and as a draftsman....Looking back, Briggs recalled:

These were experimental years; I explored new compositional approaches, new techniques or variations of old techniques and new manners of working with limited means. The fees I received from my drawings were largely plowed back into my work.... This was my chance to learn, and I worked over drawings until they were as good as I thought I could make them.Briggs learned to draw and to paint with great skill:

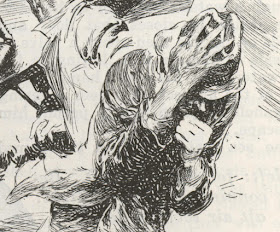

Then his art got looser...

And even looser:

Briggs became a dominant force in American illustration of the 20th century. His strong, opinionated work covered the full gamut of the illustration field, from pulps and comic strips to the movie industry to the covers of books, records and top magazines.

But the thing that interests me most about this story was that, at the height of his powers, having invested years in mastering painting and color theory, Briggs returned to simple drawing where he started. As he became more fearless, he no longer needed fancy paints or even inks. He simplified down to a pencil or a litho crayon. Art directors for prestigious magazines were happy to accept a drawing from Briggs where once a full color oil painting would've been expected. Briggs became famous in the industry for a remarkable series of drawings that he did for TV Guide, which were cited when he was inducted into the Illustration Hall of Fame:

|

| Image courtesy of Taraba Illustration Art |

If you compare Briggs' later drawings with his early random squiggles, you get a sense for how much he learned. In the words of T.S. Eliot:

We shall not cease from exploration. And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.