"What journalism is to literature, illustration is to fine art."

"Form is the fire under the pot, and content is what's in it."

"A man without an opinion is dull company but an opinion without a man is duller still."

"Many illustrators of today are too little concerned with the actualities of their time."

Robert Weaver was probably the most verbal and self-conscious artist amongst his generation of journalist illustrators. A highly articulate, socially aware and strongly opinionated artist, he became known for his bold graphic approaches in magazines such as Esquire, Fortune, Playboy and New York where he found art directors willing to give him a long leash. Marshall Arisman reportedly called Weaver "the only pictorial genius I have ever met."

The definitive History of Illustration describes Weaver's style this way:

Inspired to find new approaches to visual storytelling that were reflective of the growing interest in psychological or ideological content, Weaver ruptured the picture plane and combined discontinuous actions or seemingly unrelated ideas on one page to invite interpretation.

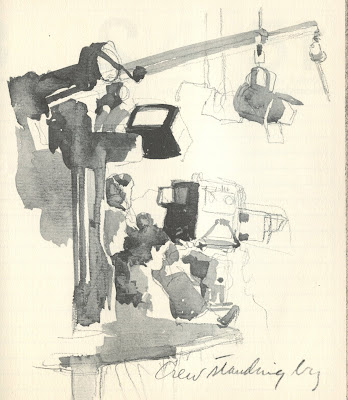

In the following series of drawings for Milton Glaser at New York magazine, Weaver gave his impressions of a day in the life of New York City police.

Weaver's concepts call for an unconventional interaction with the viewer. Sometimes his concepts couldn't possibly have been intelligible to his audience. For example, unlike

Burt Silverman who we saw reconstruct a crime scene, Weaver took pride in drawing things he had actually witnessed, so when it came time to draw a robbery he hadn't seen, he left the face of the robber blank:

A highly cerebral type but not a systematic thinker, Weaver has taken positions on all sides of an issue. On one day, illustration qualifies as art but on another day it has nothing to do with art. On Tuesdays Weaver speaks out against "amateurism" but on Thursdays he brags about being an amateur. On weekends he says no self-respecting artist could work for "large-circulation magazines" but during the week he works for Life and Sports Illustrated.

And if you happened to speak to Weaver on the wrong day, you might be in for a tongue lashing. When a youthful Bernie Fuchs first visited the Society of Illustrators and said he wanted to become an illustrator, Weaver yelled at him, telling him that was a terrible ambition, that illustration had nothing to do with art and he should find something else to do.

I like some of Weaver's drawings very much.

Like his contemporary Austin Briggs, Weaver loved using a thick black crayon with a bold, crude line.

Briggs was the first to introduce the raw tool in finished illustrations, but Weaver, following in Briggs' footsteps, was willing to take Briggs' innovation further.

Much of Weaver's influence seems to stem from his persona as well as his pictures. His boldness, his politics, his eloquence and his public handwringing about the social conscience of an illustrator attracted a huge following, even among "establishment" illustrators who he regularly disparaged. When the Famous Artists School asked Weaver for permission to reproduce one of his drawings to train art students, he turned them down with a sniffy letter:

Weaver was the only artist to withhold permission to let his work be used to teach art students. Al Dorne, the then-president of the Famous Artists School, had already seen far more of life than Weaver and was not intimidated by those "more soi-disant than thou" types: