When illustrator Mead Schaeffer was a teenager, he fell in love with a girl in his art class, Elizabeth Wilson Sawyers. He nicknamed her "Toby" because she posed for illustrations for the book, Toby Tyler.

When Schaeffer turned 20, he quit art school (giving up his full scholarship) to marry Toby and start work. The couple moved into a 6th floor walk up in New York City where they formed a team.

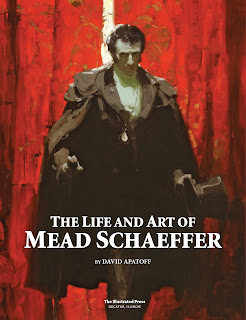

Work was sparse and times became hard. Then Schaeffer landed his first big break-- illustrating the book Moby Dick-- for the publisher Dodd, Mead.

Years later on Christmas day he confided to his children that he nabbed that first project by snooping around the desk of the art director and discovering that the assignment was about to go to N.C. Wyeth. Schaeffer intercepted the project by volunteering to paint the first 6 illustrations for free. "If any of the staff did not like the work... all bets would be off and...they would owe me nothing." The startled art director agreed to the test and handed Schaeffer the manuscript. Schaeffer wrote about bringing that first manuscript home to his wife:

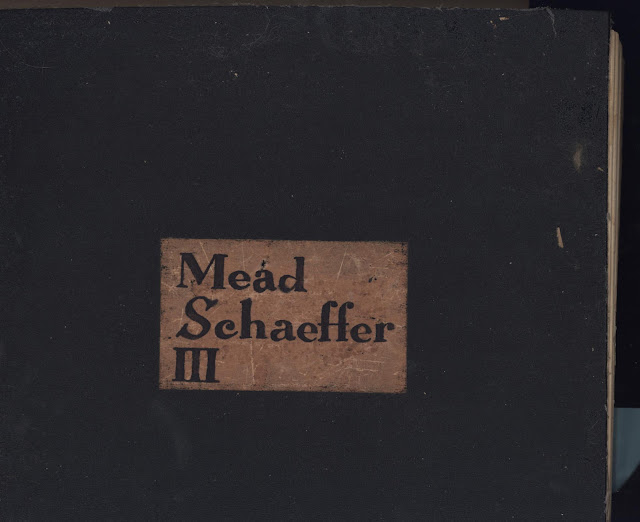

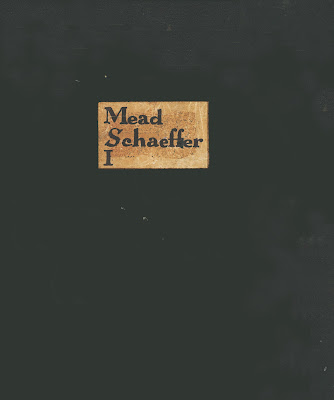

Toby became his model, consulted on the art, advised on his layouts, took reference photos and became the business manager for the team. Schaeffer began keeping a scrapbook of his work, and devoted the very first page to a large photograph of Toby.

Over a long career, Toby modeled for many of his illustrations.

The couple traveled all over the world together on illustration assignments. When Schaeffer was commissioned to illustrate Les Miserables, he and Toby sailed to France to "follow in the footsteps" of the characters. Here is the beginning of their trip:

Schaeffer wrote, "I got permission to go into the sewers of Paris and looked up old records. We returned home with costumes, books on Paris in 1848 and sketches. We returned home with wonderful experiences but very broke."

Schaeffer thought it was important to visit the sites of his paintings, walk the streets and breathe the air. He and Toby traveled to the south seas to illustrate the book Typee. They traveled to Europe. And for a series of covers for The Saturday Evening Post they traveled all around the United States.

Here are Toby and Schaeffer embarking on another illustration trip in later years:

Traveling in those days was not without its perils. The couple sailed to Asia on the Orient Overseas line, and received this certificate when crossing the international date line.

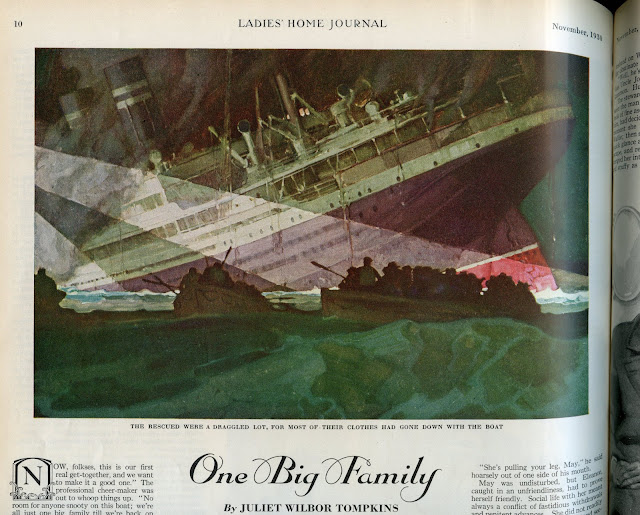

The couple flew back to the US, but their ship got caught in a typhoon on the return trip and sank with all aboard.

Toby passed away in 1973. Shortly after that, Schaeffer retired. He hand lettered an inscription about her and taped it into his scrapbooks:

Compare Schaeffer's lettering on that last inscription with his lettering earlier in his career:

By the 1970s, his classical, stately design and colors had been replaced by neon colors applied in an offbeat script on trendy paper. Apparently Schaeffer was trying to keep up with the times, even though he said,

The art of illustration has gone to hell, that's for sure.... I lived in the golden age. Now the photographer is more important than the illustrator. I'm not knocking photography but in my day you had to learn to draw better than they could take pictures.

For the graphologists in the audience, Schaeffer's lettering in his final years looks more feeble and uncertain. His outlines falter. But it seems the feelings he expressed remained undiminished.

.jpg)