There's a lot going on in this political cartoon by the great Jeff MacNelly.

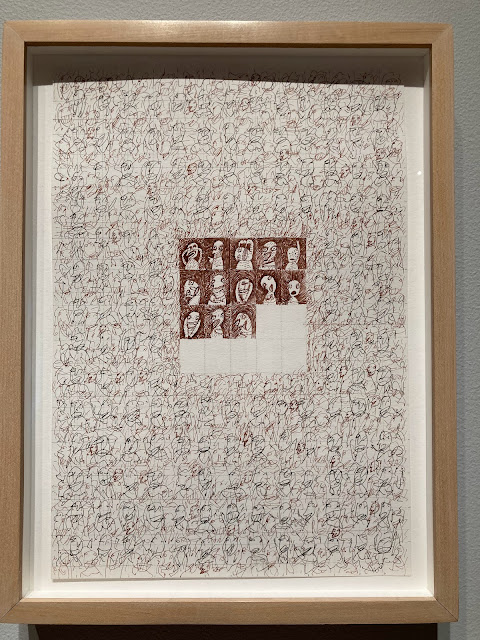

Even this third cartoon, which appears much simpler, is crafted with a watchmaker's precision.

Note the beautifully constructed face of the threatening bull: with only a reverse 3/4 profile to work with (partially obscured by a drooping ear) MacNelly does wonders with that deadly eye, the curl of the lip showing uneven teeth, the hair on the chin and the ring in the nose. Who can draw like this today?

Many artists who are able to exert this kind of control let the control dominate the picture. Not MacNelly; his drawings were always jaunty and friendly and informal. How did he do it?

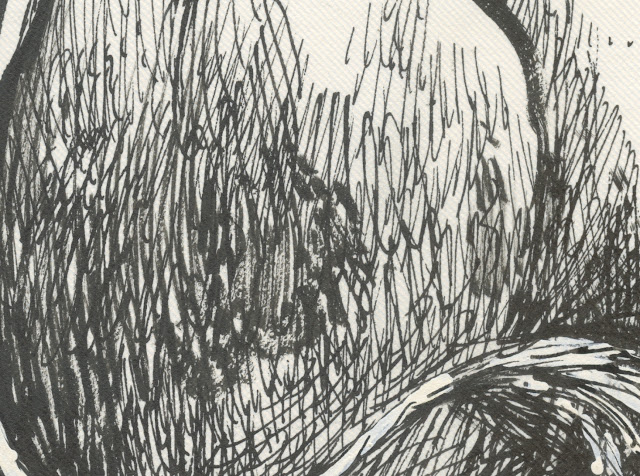

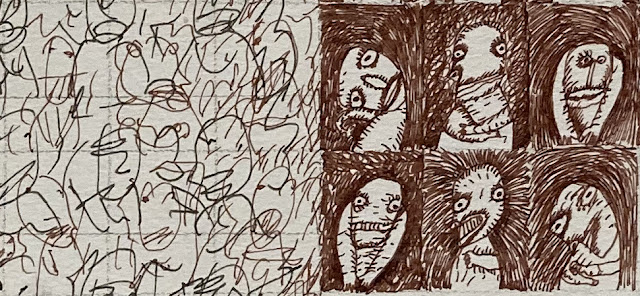

For one thing, look at how he darkened that bull. It's one wild scribble:

These disorderly, unsystematic lines infuse his drawing with life. Compare MacNelly's loose approach with the work of other masters of "control," such as Franklin Booth, Virgil Finlay or Reed Crandall. Compare it with the antiseptic technical drawing of Chris Ware and his legions of followers.

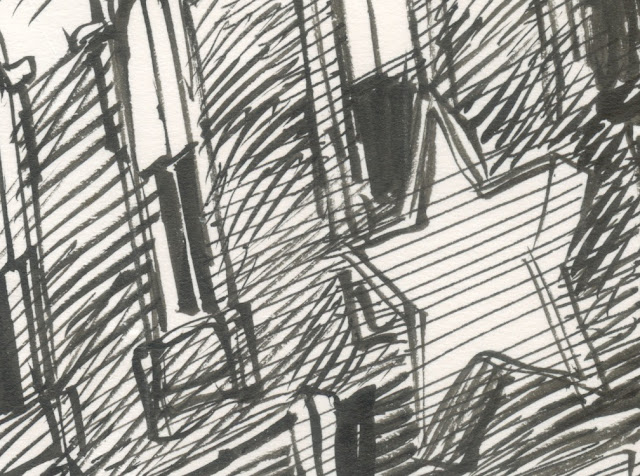

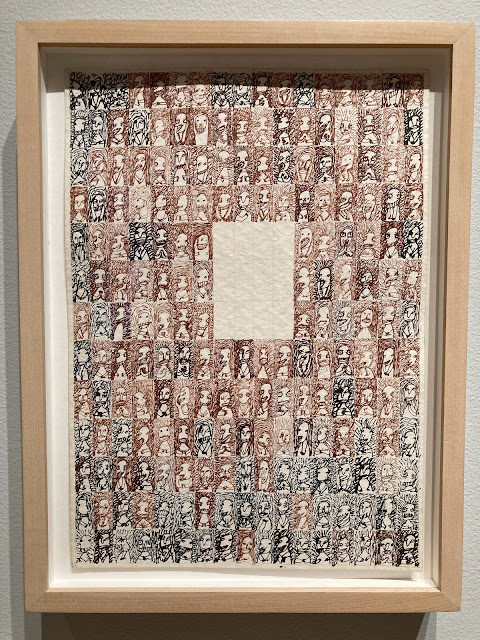

Here's another drawing with a level of detail that might prove deadly in the hands of a less certain artist:

MacNelly pulls the same trick shading that wall:

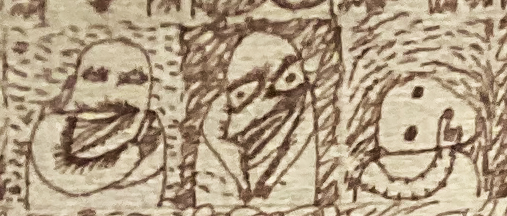

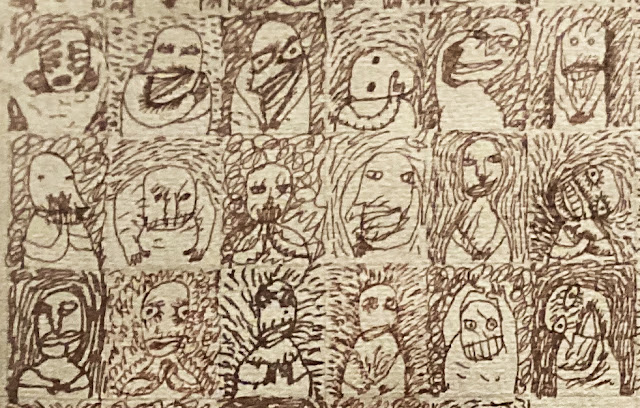

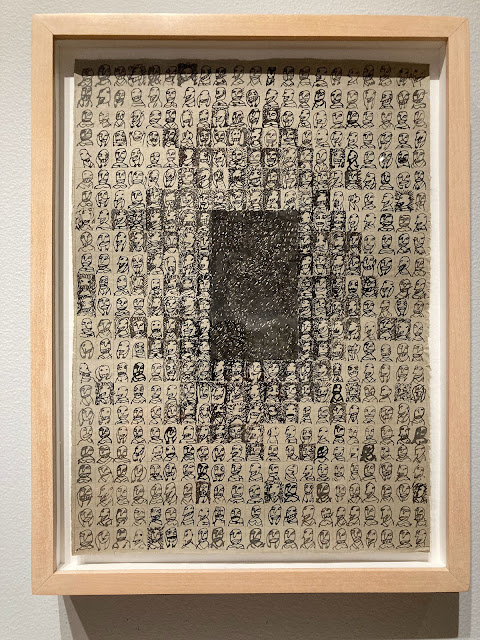

But he has other tricks too. If you're going to draw 16 distinctive people in a line, with their heads cocked at different angles and wearing different hats, you don't want them to serve as an anchor weighing down your drawing, you want them to contribute energy. I love the way MacNelly smears this crowd together with line, and draws them hugging the curvature of the earth.

It's hard to think of a more dynamic way of drawing a crowd of patient people waiting in a long line.