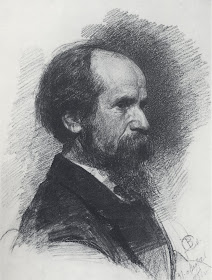

While many of Serov's finished paintings are quite beautiful, I especially enjoy his preliminary sketches for their vitality and truthfulness.

Serov, who studied under the great Ilya Repin, was part of that astonishing Renaissance in Russia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. For centuries, Russian artists had manufactured religious icons to suit the rigid specifications of church dogma.

Icons were the opposite of western illusionist art. The church historically frowned on efforts to create physical images of the holy, so Russian artists went out of their way to avoid accurate, representational images. They stressed flat, distorted figures, inverted perspective and unnatural colors to emphasize that they were painting the ideal, dematerialized world rather than the natural world. (In 815 CE, if you tried to paint a realistic icon the troops of Leo the Armenian were likely to come along and thump you on the head). But starting in the 19th century, there was a period of sunlight and fresh air which inspired a flurry of cultural activity in Russia.

It didn't take more than a generation for the Russians to shake off the dust and produce world class artwork that was nimble and probing and insightful.

With the advent of Stalin the window closed again.

But I love these pictures by Serov, not just for the images themselves, but because they help me believe that, even after centuries of confinement, artistic abilities can be reawakened on short notice if they are given the right stimulus and the room to grow.

Beautiful work. I knew of Fechin and Repin but I never heard of Serov before.

ReplyDeleteDavid, Thank you for posting this piece about Serov. I value your insights and always look forward to your informative postings. I am an Eastern Christian who paints icons and also enjoys drawing and painting in the realist tradition. I believe these styles are not mutually exclusive and can both be fully embraced. One (iconography) is for the depiction of the sublime ineffable truths of God, and the other (realist art) is for the depiction of the beautiful and wondrous creation, the work of God’s hand. They both glorify God in different ways.

ReplyDeletePlease allow me to make a slight correction to your description of Eastern Christian Iconography. Iconography wasn't discouraged by the church, but just the opposite; it was embraced by the very earliest Christians. We find some frescoes even in the catacombs of the early first couple centuries of the persecuted church. St. Gregory the Dialogist (Pope of Rome ca. 590-604) spoke of Icons as being Scripture to the illiterate: "For what writing presents to readers, this a picture presents to the unlearned who behold, since in it even the ignorant see what they ought to follow; in it the illiterate read." The need to accurately depict religious truths in art was important so that God was not misrepresented. This may be considered "rigid" however, religious art carried the weight of having to be accurate; comparable to not making errors or changes to the Scripture.

Your regarding Leo as an example of an Eastern view of art is a mistake. Leo though Eastern resides more in the camp of some western protestant churches in his view of images. In the East, Leo is considered an opponent of the Church and the Church fought with all its strength against his error of iconoclasm. He didn’t just thump someone for making a realist depiction of the divine; he thumped anyone who made any depiction. The Ecumenical Councils were held to determine once and for all the nature of Jesus Christ. Because He is not only fully God but also fully man, they decided that He can be portrayed in icons. Iconography and the Incarnation go hand-in-hand, and the taking on of human flesh and possession of both human and divine natures is the ultimate affirmation of the inherent goodness of creation. To deny the physical side of being human, or to affirm the spiritual at the expense of the physical, is simply not Christian. Therefore Iconography was considered a testimony of the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ. St. John of Damascus (676 – 749 AD) wrote, "We are led by perceptible Icons to the contemplation of the divine and spiritual."

Stephan, I am pleased to have a reader with expertise in this field and I welcome your thoughts (as I am clearly not an expert).

ReplyDeleteI assume that painting icons today is very different from painting icons 1,000 years ago. (For example, I assume today you are free to abandon the protocol of the iconostasis wall?) I know next to nothing about current practices but would be interested to learn, and would also love to see your own work. Is any of it on line?

My own understanding is that the church has historically been ambivalent about iconography. Starting from the Second Commandment (prohibiting "graven images") and extending through the Koran's prohibition of images of the prophet, there seems to be a healthy strain of resistance from the religious establishment to images of sared subjects. I understand that not all believers share this view, and that many Christians changed their interpretation of the Second Commandment sometime during the 3rd century because icons were an effective way to spread the word about Christianity. But as I understand it there were many subsequent leaders (not just Leo the Armenian) who were strongly opposed to icons for religious reasons-- mostly because they believed images would lead to heresy and improper thinking about Christian doctrine. Didn't they express concern that material images would confuse or separate the two natures of Christ in the minds of believers? I do not know whether these authoritarian (or perhaps I should say Puritan) elements of the church were correct in their thinking about the potential harm from images, but my sense is that they remained powerful over the years, and that their views, combined with the orthodoxy of the factions of the church that did accept icons, kept icons in a fairly rigid stylized mode for centuries. I don't believe these artists were free to do sharply representational work, or experiment with styles the way that artists were in the 19th century. Do you disagree with this?

Looking at the power and sensitivity of those pieces and similar work always makes me wonder what the hell were they taught back then , and how they were taught it - in terms of intensity did it make Fawcett's training seem lackadaisical ? Were students simply more dedicated and less distracted ?

ReplyDeleteAl McLuckie

David,

ReplyDeleteYou would probably enjoy Valentin Serov: Portraits of Russia's Silver Age by Elizabeth Valkenier. It's a fascinating narrative peek into Russia's art and culture during Serov's time (do not buy it for the reproductions).

I hadn't heard of Serov before. I love the loose and tight nature of these expressive portraits. Like Sargent, but I might like these even better. Totally in line with the gesture and form of his subject. I always think drawings are so much more informative than paintings.

ReplyDeleteI also might mention that, because this is an illustration bog, commerce is a consideration in those Icons. Their production was way of making a living at least as much as a matter of faith. Or is that too cynical? As a result of the restrictions the amazing emphasis on patterns became an outlet, etc.

Our current day isn't beyond this, for all the supposition that we are more free there are certainly pushes commercialy or critically that point our work in a particular direction. In the last 100+ years narrative painting has been under attack, proper figure drawing, and traditional drawing practices are marginalized. That is also why "our day" doesn't see the kind of work produced in the 19th century.

love the post! thanks

amy bates

Wow nice drawings, David

ReplyDelete''they help me believe that, even after centuries of confinement, artistic abilities can be reawakened on short notice if they are given the right stimulus and the room to grow."

ReplyDeleteI agree David, it is interesting note how fast basketball developed, or most sports skills have developed in such a short amount of time, once everyone agrees on the rules of the game.

Al McLuckie-- a fascinating question. I have my own theories about this, as I'm sure everyone else here does. I should probably read the Elizabeth Valkenier book recommended by Etc. etc. before venturing an opinion. But I do know this era in St. Petersburg was one with an intense work ethic. People had an elightenment focus on the value of knowledge (cultured people spoke several languages and were always thirsty for news of the latest trends from Europe). That couldn't have hurt.

ReplyDeleteEtc. etc.-- it is very difficult to get good reproductions of Serov's work anywhere, even on the internet, which is why I offered these. But I would like to read more and I see that Valkenier's book is available on Amazon, thanks. Would you like to proffer at least a preliminary answer to Al McLuckie's question, based on the book you've already read?

Amy Bates-- thanks for writing. Yes, Serov painted in the era of Sargent and Zorn and they do share that "loose and tight" style that requires so much hard work to acquire technical skills, followed by the strength of character to selectively put them aside. I agree with your assessment (although I'm still hoping to hear back from Stephan with more first hand experience with icons).

Tom-- Thanks! I am always a sucker for great drawings and preliminary studies. Serov's finished paintings, especially his portraits, were also drop dead gorgeous. I think I'll show a selection of them in the future but right now these sketches get all the focus.

ReplyDeleteDavid,

ReplyDeleteIt's been several years since I read the book and that's a very difficult question. The impression Valkenier gives is that there was a tremendous amount of symbiosis in the arts, such that a painter like Serov (also a scenic painter) was closely associated with people like ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev. Whether that's the answer or not I can't say.

Implicit in this discussion of Serov (not to mention Repin, Vrubel, Levitan, Kramskoy and others) is how Paris-centric art history dealing with the period 1860-1920 is. Times seem to be changing, however, and books and exhibits can be found dealing with very good artists who were based in Italy, Spain, Finland, Denmark, Scotland and other "artistic backwaters" in those years. (Yes, many of those same artists did their study stint in Paris, but fat lot of good it did them so far as art history is concerned.)

ReplyDeleteTo see Serov, et. al. in the canvas, one needs to visit both St. Petersburg and Moscow. The place to go in the former is the Russian Museum (not the Hermitage) and in the later, the best bet is the Tretyakov Gallery. Moscow also has the Pushkin Museum, which has some worthwhile paintings, but I didn't get around to visiting it when I was in town a few years ago.

Don Pittenger-- I agree that Paris hogged the spotlight from 1860 to 1920, just as New York hogged the spotlight from 1945 to 2000. When I wandered into the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, I was astonished at the number of brilliant artists lining the walls who were never mentioned in my art history books (including abstract expressionist work by Malevich several decades before abstract expressionism was "invented" in New York). I enthusiastically join in your recommendation about museums to visit.

ReplyDeleteI especially recommend to all readers Don Pittenger's excellent blog post about his visit to the Sorolla Museum in Spain. Sorolla is another under appreciated painter and Don's treatment is superb.

I think we're missing the kingdaddy of all art centers that have gotten the short shrift by dint of art history, and that is Germany and its related areas.

ReplyDeleteAnd the reason for this is that Modernism's sworn political enemy is Romanticism in all its manifestations (and Modernism remains in control of art history).

I believe it was the influence of Romanticism (and its philosophical cousin idealism) that opened Russia up to more liberal attitudes in the arts in the first place.

Thank you squire. I really like these. Well, apart from the iconograph(? is that a word). And that last one, of the woman. Were I to see her in real life, I do believe I'd run to the end of the earth to get away. It's the type of face that launched a thousand nightmares and I fear she may seep into mine. There are mathematical calculations to do with the sag of the lip -vs- the degree of droop of the left eye -- among other parameters -- that would no doubt serve as a model from which to judge whether one's sketch qualified as sufficiently sub-psychotic with tendency towards crack abuse and witch status. Which.she.is. Perhaps you should have put the religious image closer to her to help counter the evil. Going back under covers with torch now.

ReplyDeleteEtc. etc.-- symbiosis, along with work ethic and civil unrest, seems to leave its footprints around every great cultural flowering so I would not be surprised. In this case, I think there was symbiosis not just between art and music or theatre, but between Russian and European cultural traditions. That cross-fertilization business always seems wildly fruitful.

ReplyDeleteKev Ferrara-- do you have some German artists to recommend? I am in awe of what the Germans were doing in music and literature at the dawn of romanticism, but I have to confess that I don't think of their painters in the same league as these Russian painters. Did they have a Repin / Serov / Koren / Kandinsky / Malevish / Fechin cluster of artists?

Peacay-- I'm sure this poor Russian woman was very vain about her looks and was giving Serov her very best smile when she posed. I guess we can tell what Serov thought about her. You remind me of the time that a wealthy heiress went to Ivan Albright, an extremely important painter who painted everything in a dark and awful manner, and commissioned him to paint her portrait. Her socialite friends, who were all having vanity portraits painted, thought she was crazy. The result was this wonderful portrait. She looks far worse than Serov's woman on this blog post, but all of the portraits of her friends are gathering dust in the attic (or have been cast on the junk heap by ungrateful grandchildren) while this Albright portrait hangs in prime space in the Art Institute of Chicago. Apparently the heiress decided she could withstand an unflattering portrait to be associated with artistic greatness. I always admired her for that.

David, you probably already know this German artist, but worth checking out. Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel.

ReplyDeleteI wrote "Germany and its related areas", because all the wars leading up to WWI made a hash of all the maps. Generally the Romantic movement had its center in Germany, but the movement extended a bit north, south, east and west.

ReplyDeleteThere are many interesting artist who came out of The Dusseldorf School, Art Academy in Munich, The Vienna Academy, etc.

Just to name a few, Hans Gude, Gustav Klimt, Hans Makart, Arnold Bocklin, Eugene Neuhaus, Kathe Kollwitz, Max Klinger, Von Stuck, any number of California tonalists studied in and around Germany during the Romantic era... I have hundreds of images created by artist who studied or worked in and around Germany during the Romantic period in my files. Too many to name.

You mentioned Kandinsky, but he and Klee both studied with Von Stuck in Germany.

Having said that, I prefer Fechin and Repin to any of those I've named. And while Rhineland Romanticism is unjustly unsung, Paris, as a great center of the arts, is justly sung.

The "father" of Russian Romanticism is: Карл Павлович Брюллов a.k.a. Karl Briullov a.k.a. Karl Bryullov a.k.a. Carlo Brulleau a.k.a. Carl Bruleleau (1799-1852).

ReplyDeleteKev,

ReplyDeleteNo love for the Nazarene movement, I presume?

His subjects may be too saccharine for some and he predates impressionism (i.e no razzle dazzle brushwork), but I think Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller was a very competent painter in the Romantic realist tradition.

Not really hip to the artwork of the Nazarenes. They seem kind of like Titian and Raphael knock-offs. But they did help aesthetics along by rediscovering older Italian principles of composition, and passing them on. Particularly Wilhelm Von Schadow (can you beat such a name?) who ushered in the Dusseldorf school, which I greatly admire.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the introduction to Serov. Each one of these is positively alive - in a way I've never seen captured in a photograph. It reminds me of the tragedy of this kind of work having been completely supplanted by photography, and perhaps the key to its revival.

ReplyDeleteHi David,

ReplyDelete"Do you disagree with this?" It isn't that I disagree with this idea, what I am trying to say is that icons and objet d'art are in two separate realms. In the east the representational, realist type artwork does exist and is expressed in Russia and all throughout the east... it just isn't used in a Liturgical setting. Icons are painted a certain way because of what their function is. They are somewhat abstract and symbolic not emotive. They are used in worship, not just as decoration of the church building.

Actually the only thing that differs between 1,000 years ago and now in painting icons is the paint medium. Some still use egg tempera and others use acrylic. Other than that, like pretty much of everything else in Orthodox Christianity, nothing has changed. Yes our churches still have the iconostasis. Unfortunately I do not have a web site but if you email me I can send you a few images of icons I have painted.

Iconography in the Orthodox Church isn't seen as part of the "prohibition" against images. As a matter of fact when we do a careful reading of the passage against graven images it is about foreign idols. Because no sooner had the Lord commanded not to have any graven images in Exodus 20 did he then command to make a graven image of angels and place them on top of the Ark. Later when Solomon's temple was built he commanded to make even larger angels (1 Kings 6) carved and gilded to be about 15 feet high by about 7.5 feet wide each. They were important elements because they were teaching us.

Historically there were 2 relatively small periods of time that Iconoclast Emperors ruled and imposed there iconoclasm on the church. The second time was a much worse situation because the iconoclasts literally smashed and destroyed many precious icons from the ancient church and persecuted iconographers and any that possessed them. Basically David, the real crux of the problem is the failure of the iconoclasts to recognize that God became flesh in Jesus Christ. This has been the historic understanding of Christ since the first century. This is what the Seventh Ecumenical Council decided when they addressed the use of icons in the Church. We sing this hymn in the Church commemorating the event of the restoration of icons.

"The Son who shone forth from the Father was ineffably born, two-fold in nature, of a woman. Having beheld Him, we do not deny the image of His form, but depict it piously and revere it faithfully. Thus, keeping the True Faith, The Church venerates the icon of Christ Incarnate."

And on the Ninth Day... Fear, Idealism, and Ignorance combined to create the Supernatural.

ReplyDeleteAnd the frightened monkeys were subdued by their own credulity. Amen.

How could anyone not get excited looking at that first study (which looks like it might be of Repin) just masterful draftsmanship. I saw Serov's finishes when the Russia show passed through the Guggenheim a few years back, but these are a real treat. Thanks for posting them.

ReplyDeleteIdle Worshipper said...

ReplyDelete"And on the Ninth Day"

If you were half as rational as you presume yourself to be, you could clearly see that the deeply disturbed emotion in your comment is far removed from rationality.

Say Amen, like a good little monkey. Or else the Gods will get angry and make lightning! BOOGA-BOOGA!

ReplyDeleteRE:.. ... eons! Yes, Fawcett would say that it is all about the powers of observation. If you have eyes that can probe and analyze the human form...

ReplyDeleteBut eons can pass in the blink of an eye, a child goes to college, a trip to Philly and all of a sudden one misses that fun, the words, the writing...the ART !

Now for Serov, its about as far from Victorian valentines as one can get! Not my cuppa tea.

I wonder where the warrior pilot is, I've been out of the loop.

fond gruesse

einbildungskraft

Tom, Kev and अर्जुन-- thanks for the recommendations for German area artists. I knew and have enjoyed the work of some of these (and wrote about some previously, such as Gustav Klimt, Arnold Bocklin, Kathe Kollwitz, etc.) but several were new to me and I enjoyed making their acquaintance. I appreciate the referrals.

ReplyDeleteAnthony-- I agree with you; no photograph can do this.

Idle worshipper / your worshipfulness-- I think you will find that the most effective critics of organized religion (Nietzsche, Voltaire, Bertrand Russell, etc.), whether they were trying to be sarcastic or serious, were the ones who put a little more substance on the table. It's difficult to dismiss Tolstoy, T.S. Eliot, Rembrandt and Michelangelo by simply calling them "monkeys."

Not related to this discussion, but some other artists worth checking out from the same era are Sydney Laurence and Sydney Long

ReplyDeleteStephan,

ReplyDeleteThank you. Having an iconographer's explanation of the history and theology of the art is interesting and cool.

David,

Thanks for this blog. It is always interesting. I rarely comment but always read.

Tim Langenderfer

Valentin Serov is brilliant!!! You feel as if you could actually touch these people.

ReplyDeleteTeh reason the russian bizantine artists didn´t use perspective in their works is a rather more mundane one: perspective in pictures was only invented many centuries later, in Italy:

ReplyDelete"In about 1413 a contemporary of Ghiberti, Filippo Brunelleschi, demonstrated the geometrical method of perspective, used today by artists, by painting the outlines of various Florentine buildings onto a mirror. When the building's outline was continued, he noticed that all of the lines converged on the horizon line. Soon after, nearly every artist in Florence and in Italy used geometrical perspective in their paintings,[13] notably Melozzo da Forlì and Donatello. This became an integral part of Quattrocento art. Not only was perspective a way of showing depth, it was also a new method of composing a painting. Paintings began to show a single, unified scene, rather than a combination of several."

To see more:

ReplyDeletehttp://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Evolution_of_Perspective