As far as I know, Toulouse Lautrec was the first illustrator to develop the technique of making solid colors more vibrant by painting them in a series of chopping, vertical strokes.

|

| Lautrec |

His contemporaries made colors shimmer by painting them in dots or stray marks, but Lautrec's paintings always seemed more vigorous to me because he used slashing marks, drawing rather than modeling with his paint brush.

|

| Lautrec (detail) |

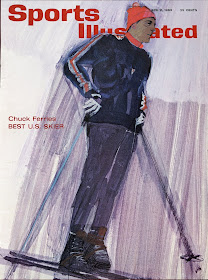

Years after Lautrec died, illustrator J.C. Leyendecker used a similar approach, painting everything in slashing strokes, but Leyendecker enhanced the style by tilting his strokes at a jaunty angle.

|

| Leyendecker |

Using this technique, his pictures looked more vigorous and lively than the work of other illustrators.

Boy the solidity of the drawing in the Lautrec and Leyendecker is like a breath of fresh air after seeing so much paint sliding down the face of the paper in the pervious post. Hard to beat an individual's experience of real life as opposed to the experience of photos.

ReplyDeleteWith Lautrec and to a formalized extent, Lyendeker, the rain-like application of paint was a means of fine-tuning the control of tone rather than a means of adding vibrancy - it is the same principle as that used in cross-hatching with drawings, but employs coloured paint. It is used extensively in tempera painting (from Botticelli to Wyeth) as a way of overcoming the medium's resistance to blending due to rapid drying. (Lautrec painted a lot in gauche which has the same characteristic as tempera)

ReplyDeleteBut the illustrators of the 60s amplified and extended the principle to become one of the tools in which to make the handwriting of their pictures expressively conspicuous.

I thought Lautrecs work looks like drawings because they are drawings; oil pastels hit with turps and the occasional very thin wash of oil paint with gouache whites

ReplyDeleteI need to look into this

You've made me appreciate that Fuchs-look more, David. I just needed someone to say it in a way I could relate to it. Many thanks

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteDavid you do notice that the "slashing marks," in the Leyendecker and the Lautrec hold to the planes of the form? They are in sympathy with the surfaces of the masses that compose the paintings. They are "tilting at a jaunty angle," but they harmonize with form while the illustrators work the titled lines general only contrast with the vertical and horizontal orientation of the page itself. The way camera angles are raised, lowered and titled to make rock bands look more exciting in videos.

ReplyDeleteLook how the slashes in Leyendecker 's snowman hold to it's vertical planes or how the "slashes" in the young man's coat follow the minor axis of its planes. Lautrec does the same in his painting, not as explicitly as in the Leyendecker, but with the green slash marks holding mostly to the halftones giving them a vigor in contrast to the light and shadow. In the headboard his verticals slashes like the Leyendecker contrast in opposition to the long axis of the headboard creating a strong vertical mass that holds the pillows up and emphasis and support the titled, inclined angle of the sleeping position of the girls heads. The main woman's head beautiful contrasts and sympathizes with direction and orientation of bed (or should I say picture) her face holding the viewer in place and preventing us from exiting the picture to the right. It is a wonderful tension.

"(Whereas nobody successfully copied Leyendecker ever.)"

ReplyDeleteRockwell said he tried Leyendecker's medium but found it too slippery. The medium is probably key to the success of this effect in his hands. The formulation has to be such that strokes don't melt or mingle into the paint layer below, while maintaining a certain crispness, but not to crisp.

There has been an ongoing movement to downplay both the influence of paint medium on the look of the finished painting and the complexity of formulas used by various artists. There may be some merit in this as a reaction to mediums that went too far towards the convoluted, resulting in technically disastorous paintings. But to believe that Rembrandt or Holbein got their effects from simple oil and turps and is to not have a clue what you are looking at or experience in trying to produce similar results.

As far as expressive drawing, indeed. The old Italians had unmatched vigor and fluidity in figure drawing without all the slashing. But a superficial environment produces superficiality, so...

Chris James,

ReplyDeleteWhile JC Leyendecker did use an unique formula of Stand Oil, Turps, and Linseed... I don't think it was the reason for how he developed his style. For one thing, prior to Leyendecker telling Rockwell the formula, Leyendecker's brother FX Leyendecker also knew the formula and for decades. And FX had a different style than JC. Or at least, different enough to appreciate that JC was thinking differently about brush strokes than FX.

Tom-- There's no question that Lautrec and Leyendecker were very, very good-- two of my all time favorites. And I've tried to show a cross section of art by a dozen different later artists, all good but most not nearly as good as Lautrec or Leyendecker, to show the breadth of a trend. I'd disagree, however, that the later pictures we've discussed are merely "paint sliding down the face of the paper." I think we are witnessing different art for different times, and we couldn't go back to the old style even if a new artist could paint the way Leyendecker or Lautrec could. Remember that in the 1940s Leyendecker could not find work. His old fashioned style was considered "washed up" and no art director was interested anymore. His original paintings were sold off for a pittance in a yard sale.

ReplyDeletechris bennett and Richard-- My favorite reference book on Lautrec is Lautrec by Lautrec by Huisman and Dortu. It discusses Lautrec's painting techniques and even reproduces his drawings of himself painting. Many people considered Lautrec to be a graphic artist because "during his lifetime Lautrec was known primarily as a poster-designer and illustrator." The book includes a catalogue of his graphic works, so we can see the very substantial number of pictures he did using a lithography crayon, or pastel, or the drawings he colored in with water based medium. However, his paintings (including the one shown here) were largely in oil, painted with brushes and using turpentine as his medium. The book shows his palette (which he simplified by using neither bitumen nor raw sienna) and discusses the techniques he learned from his teacher, Cormon. It says that the mature Lautrec "would often begin by roughly outlining the whole of a picture with light brush-strokes in violet, or occasionally in vermillion or carmine."

Standby4action-- I'm very glad to hear it.

ReplyDeleteKev Ferrara-- You make some interesting and very substantial comments abut the way Leyendecker fits into this chronology, and I've enjoyed reflecting on them. I'm sure that Leyendecker's technique does all that you say and more. He was absolutely brilliant, a true master of color and value. Having said that, I think that his diagonal slashing lines gave his oil paintings the crispness and excitement of graphic art and that accounted for a large part of his popularity. No matter how beautifully blended his colorvalues were, it's impossible to ignore how they were interrupted by those hard edge lines, and that was his major advancement over what his teachers Bouguereau, Constant and Laurens at the Julian in France. Without that striking innovation Leyendecker would have spent his days polishing the shrine of Bouguereau and might have died another anonymous and obsolete academy painter.

There's no doubt that Leyendecker "earned" his results compositionally, perhaps like no other illustrator of the 20th century. He still eschewed photography 50 years after Lautrec used it to get beautiful results, and he watched his career decline as Rockwell and other contemporaries recognized the Saturday Evening Post's requests that they start painting covers that depended on photography. He was a purist, and frowned on student attempts at experimentation when they should be copying the greats: "There is plenty of time for that later, but for now do not try to improve upon the masters."

Young Bernie Fuchs had none of the formal education or opportunities of Leyendecker, he never copied a master, and at age 20 he was just trying to keep from starving to death. What his many inventions lacked in technique, they made up for in energy, excitement and mood. In the 1960s those were the coin of the realm. If Leyendecker had tried to paint for that market (https://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2014/12/remembering-our-debts.html ) he would've ended up sitting around a hobo campfire in a train yard in Duluth.

In short, I share your view of the quality and value of Leyendecker's contribution but I disagree with you about the quality and value of alternative approaches. Rockwell worshiped Leyendecker but talked about a missing ingredient: "He didn't look at a picture as ... a scene with flesh-blood-and-breath people in it; he saw it as a technical problem. Whenever he was tired and discouraged about a picture, he'd just put more technique into it. And technique alone is a pretty hollow thing." I think Howard Pyle and Harvey Dunn would recognize this concern. You would not turn to Leyendecker for the thrill of those Bob Peak cheerleaders-- his compositional integrity would not have allowed him to twist the hand of that lead cheerleader that way. You would not turn to Leyendecker for the mood of a Fuchs glowing sunset on a road. That wasn't his thing. But those are things which, I believe, have value in art.

Tom wrote: "you do notice that the "slashing marks," in the Leyendecker and the Lautrec hold to the planes of the form? They are in sympathy with the surfaces of the masses that compose the paintings. They are "tilting at a jaunty angle," but they harmonize with form while the illustrators work the titled lines general only contrast with the vertical and horizontal orientation of the page itself. The way camera angles are raised, lowered and titled to make rock bands look more exciting in videos."

ReplyDeleteI think your "rock band" analogy is very apt, although you could've said it about the camera angles in Citizen Kane as well. I think those have become established principles of 20th century aesthetic; they now seem like cliches that can be fairly easily appropriated by less capable artists. Once people figure out that placing the camera on the hood of the race car creates a sense of power, or blurring the passing image creates a sense of speed, it's not hard for anyone to do. Yet, these techniques interact with our five senses in a way that remains very effective, and we shouldn't give them up just because they work for the less talented as well as for the originators.

I agree that the "slashing marks" (we must come up with a better term for those things) hold to the plane of the form, if not perfectly, then "in sympathy" with the form. (Note that the angle of the slash is different on the back and front of Leyendecker's coat.) I think that Lautrec's lines are a little more free-- for example, those lines on a flat wall in the background don't describe form at all, they simply add movement to the color. But isn't that the whole point? If you want to simulate an explosion, you can't hold to the plane of the form. I think the message here, like the message of a Franz Kline painting, is that the energy has jumped the fence and escaped the corral. I think that at the beginning, art directors objected, "Say... wait a minute, you can't do that. Those lines are supposed to hold to the plane of the form." But people loved it, and like all good art movements it became self-legitimizing.

Chris James-- I understand that Leyendecker was very proud of his secret formula for a medium, and he did call upon it for an unusual combination of blending and hard edge (note the detail close up of the pocket in this Post). I'm sure he refined it through much trial and error. Today we can achieve that combination of blending and hard edge through Photoshop.

You say, "The old Italians had unmatched vigor and fluidity in figure drawing without all the slashing." But today artists are surrounded by speed and power far beyond the wildest dreams of the old Italians. Speed and power at which fluidity breaks down and details are lost in a blur. When Leonardo wanted to draw power he drew a thunder storm or soldiers on horseback clashing. Who knows how he might have depicted a huge rocket launch with the colors and mediums available today.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteDavid: "it's impossible to ignore how they were interrupted by those hard edge lines, and that was his major advancement over what his teachers Bouguereau, Constant and Laurens at the Julian in France. "

ReplyDeleteI also think you're putting too much importance on that particular stylistic element.

What jumps out at me about Leyendecker's 'style' isn't the diagonal striping in the rendering (which varied quite a bit in intensity), but the way his eye sculpts the forms. He reduces reality to some point between 'realism' and 'cartoony' then tweaks and chisels the form to (his version of) perfection. It's a type of 'idealism' which is instantly recognisable as his, but which often leaves his characters looking more like coloured statues than real people. Perhaps this is what Rockwell was sensing in your quote ... ""He didn't look at a picture as a scene with flesh-blood-and-breath people in it; he saw it as a technical problem" ?

Rockwell moves the dial toward 'realism' away from 'idealism' and you get that more tactile sense of reality from his work. Of course, photographic reference played a big part in that move, but Rockwell seemed very sensitive to the smudgy, slightly lived-in look of real life with all of its imperfections and brings that in, in the details he chooses, the way he renders the patina of surfaces, and the more naturalistic acting.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteDavid wrote

ReplyDelete"I think that Lautrec's lines are a little more free-- for example, those lines on a flat wall in the background don't describe form at all, they simply add movement to the color. But isn't that the whole point? If you want to simulate an explosion, you can't hold to the plane of the form"

Kev's right! the marks are the drawing! They follow the planes the way a cornice follows the mass of a building. What makes the drawings good is the perfection of the planes which allow their line work to forceful express the strength of things. It would be much more glaring and disturbing if the did not! It would destroy the picture’s harmony. It would denied the eye its journey. Like that titled aircraft carrier sitting on a vertical plane of the page in the pervious post. Good artist see how things relate while most people just see the differences between things.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThe portion of those marks that defy the descriptors that actually set the wall upright and flat, lift off from the wall and add a sense spatialization for want of a better term. This spatialization is a poetic idea that, to some degree, suggests air in the room at various depths in front of the wall, or a lack of focus on that area, or a scumbling of emotions, etc.

ReplyDeleteYes indeed Kev. It is being used to the same end as sfumato which I should have mentioned along with my point about controlling tonal and chromatic dosage - so I thank you for your thoroughness on the matter.

'Spazialization'as you call it is, I believe, what the technique of Sfumato is doing and as we know was the core pictorial handwriting of Leonardo, Dewing, Inness and Carriere to name just a few. But I believe the principle of 'spatialization' to be at the heart of drawing itself. And painting is drawing with colour. (So it is no accident that Lautrec's technique has prompted this) In all pictures the touches of graphite, ink, pastel or paint are never figuratively the substance of what they are evoking but a bunch of abstract relationships coalescing to embody the illusion of form (I know you know this - you've been a key part of my education!). And I think it is no accident that the weave and weft of the best artist's work, their pictorial facture, reveals their understanding of this and realizes it in many forms: the disembodied matter of Constable (most obviously in what his contemporaries referred to as 'Constable's Snow', the 'light as settled dust' in Chardin, the plasma of Monet and Turner, the crumbliness of Gwen John, the eddying stream of brush strokes in Sargent etc. The flatter or textually quieter shapes of Walter Everett and Euan Uglow are not an exception to this (in my view) but the same principle employing larger units. That is to say: I believe 'spacialization' to be the aesthetic result of the abstract autonomy of an image's fundamental building blocks.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteKev ferrara, Tom and chris bennett-- I don't mean to be thick, but I just don't get it. The "marks" that I'm talking about in the Lautrec don't create "spatialization." The spatialization is created by the hue and shade of the paint combined with the perspective established by the drawing portion of the painting, all of which could be done just as well without those vertical hatch marks. The marks I'm talking about, whether in the background or foreground, on the wall or the blanket, are the same length and thickness, the same value, in the same vertical position, spaced the same distance apart. They work counter to the flow of the form (just as the later generations of illustrations would do). For example, the hatch marks on the blanket do not recede with the plane. They do not wrap around the figures. They have, liked later generations of art, jumped the fence and escaped the corral of academic form. So I need someone to explain to me how that creates spatialization. It seems to me the role of these marks is to add vitality to the composition; the atmosphere itself, regardless of where it is located in space and regardless of whether it is a liquid, a solid or a gas, begins to coruscate like busy subatomic particles (a harbinger of things to come in art).

ReplyDeleteKev Ferrara-- that's an excellent quote from Bedell Stanford, a real keeper. For an in depth exploration of the stereoscopic character of creativity, I highly recommend Arthur Koestler's The Act of Creation.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteKev Ferrara wrote: "To the extent that any marks alienate from rendering per se, they detach from the rendering and float in some vibratory or holographic way above or beyond the realism, toward or away from the viewer - causing a sensation that the 'realism' is somewhat transparent or ethereal."

ReplyDeleteOK, that helps; we are seeing and talking about the same phenomenon, "above or beyond the realism." There are books about spatialization and spatiality that describe it as "a key concept in literary and cultural studies, with critical focus on the ‘spatial turn’ on the traditional literary analyses of time and history." If we were talking about that, I'd have to step back and let you fly solo.

You say, "*Any* effect causes vitality." Well, errr, yes, but some marks cause people to sit up and take notice, to feel energized and excited, even in a culture that had already become saturated with images. In order to achieve that, artists had to give themselves permission to loosen the bonds to realism, the way abstract expressionism did. The way Lautrec did in the picture I posted. The weaker those bonds, the more suspicious you seem to become. I don't disagree that "The qualitative question is the justification of the effect for any particular spot it is used. And whether it is used elegantly, and in a personal way." But to what authority is it justified, and what form must that justification take? I think the brave artists of the 60s were self-justifying. In hindsight, some of it held up and some of it didn't.

On the subject of Arthur Koestler, I'm playing a drinking game with you. Every 5th time you invoke Harvey Dunn, I invoke Koestler.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteKev,

ReplyDeleteThank you for such a richly considered reply. Sorry for the delay in my response but the idea that superposition of any effects causes the sense of depth not just optically but aesthetically is new to me and I needed a little time to digest it.

The principle, so far as I can tell, seems true. I can see how it works for 'specialization' in its Lautrec(ian) form (…the particular quality Lautrec achieved on that wall; where the non-descriptive scumbling alienates and lifts off from the flatness and hovers in front of it, 'spatializing' the area in front of it (the space of the room, as it were) but to check I have you right I’ll apply it to what I consider to be the deeper principle of ‘spacialization’ alluded to by my other examples.

When we start a picture there is nothing being evoked but the void of the canvas and we almost exclusively interpret the individual touches of paint not as figurative entities but as the components of relationships that will coalesce to evoke an intended sense of form. But as these forms are conjured into being we are seduced into believing the paint touches are actually part of the forms being depicted so there arises a ‘literal’ component to our experience as well as the sense of evocation through abstract relationships. This, as I understand it, would be the creation of aesthetic depth through superposition.

David wrote:

ReplyDelete…I just don't get it. The "marks" that I'm talking about in the Lautrec don't create "spatialization. (…) They have, liked later generations of art, jumped the fence and escaped the corral of academic form.

When we draw (with pencil or paint) the marks never represent anything in themselves. So to consider the Lautrec: The individual lines on the cheek or pillow or blanket or headboard are not part of the things themselves or their shadow or colour, and neither are the outlines (around the nose, say). The marks are abstract relationships that evoke the sense of form.

OK so far. And you are right to suggest that if Lautrec’s pictorial handwriting had been different it would have conjured up the same scene. But the aesthetic experience communicated of how he has built those forms would be different. In this image (and his art in general) they are sensed as airily knitted structures embedded in a pictorial either of their own making. His particular mark making is not an add-on visual excitation filter “jumping the fence and escaping the corral of academic form”. It draws the forms, that is to say; communicates how he internalizes and then embodies it.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThanks Kev for such a comprehensive reply and taking the trouble to articulate it so clearly - I noticed you edited it since originally posting in the interests of greater lucidity and I thank you kindly for that as well, I'm sure it's greatly appreciated by others here as well as myself.

ReplyDeleteIt seems from your unpacking of the principle relating the the evocation of sculptural form that I have understood the general mechanism but not appreciated quite how it works regarding the particulars. Having digested some of this overnight (hopefully) I was keen to see how it would relate to my painting practice this morning. 'Curiously liberating' is all I can report of my feelings at this early stage. I'll say some more on that when I become clearer which hopefully wont be too long. Until then, thank you again.

Mr Mcafee, you are a slug on the cabbage.

ReplyDeleteOne of the advantages of using McAfee is its ability to delete the threat once detected.

ReplyDeleteProtection Across Different Apps – McAfee protects all the apps on your device from attacks.

Real-time Scanning – Since you can’t run a per-second check of each file on the computer, McAfee antivirus products help. It often checks your device for malware and other malicious codes.

Having learned about the benefits of McAfee products, you should want to install and use it. But, you should have a McAfee account to enjoy these security features.

So, let’s discuss how to create an account, download, and activate McAfee on your device.

hrefs

mcafee.com/activate

www.mcafee.com/activate