It has been a while since I've shared another reason why I like the work of illustrator Robert Fawcett.

Even at the height of his career, Fawcett continued to sketch from the model every week. At the end of each session, he'd open the lid of his model stand and toss in the day's efforts. When he died, there were several hundred drawings stashed there.

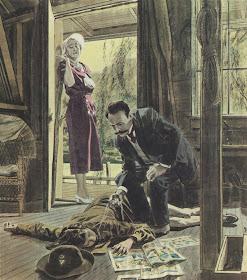

One result of Fawcett's continuing commitment to observation is that when he illustrated a figure, he was not content with the usual simplistic shortcuts: symmetrical people standing perpendicular to the ground. Instead, he observed that people are often bent or lopsided, reflecting life's tug of war between gravity and organic matter:

One of the ways Fawcett's life drawing regimen paid off is when he received an assignment to depict a limp figure-- someone whose muscles went slack and who collapsed in a jumble-- Fawcett was able to capture such figures in a very convincing way. Again, no stereotypes here.

Fantastic - every time I look through your book on RF , it's as fresh as the first time . His fig. drawing books are something I review often - wish vol. 2 was coming --- of all your books !

ReplyDeleteI agree that a volume 2 would be lovely, especially on Fawcett. I notice that Manuel Auad's website ad for the Briggs book states, "I do not reprint." True so far, but I wish he would make an exception for the Fawcett book. I've got my copy--but some things deserve to be kept in print.

ReplyDeleteLook again at Michaelangelo's Pieta. What gives the expression of limpness is not the amazing mimesis, but the draping, near dripping liquidity of flesh suggested by the expression; an idea which clearly guides the rendering from within.

ReplyDeleteI don't feel the limpness in these figures. I only see academic life drawings of models playing dead on the model stand; schematic accuracy, textural accuracy, surface accuracy. The excellences of Fawcett's efforts and plain to see and appreciate, but what is there to feel beyond that? His compositions are perfectly acceptable and often interesting solutions. But they are ossified by being forced through his obsessive descriptive compulsions, then washed out by his dull values and dull colors. I know he wants me to admire his drawing, and he's succeeded at that. But is that a worthy artistic goal?

I know I should leave out the color commentary per se, because he was deficient from birth in that area. However, his work not only lacks good color, but in over-describing in the lights, outlining dogmatically, and going ahead and stating general dull colors and general dull values, he leaves no room for the viewer to even imagine good color or light effects where they might have been. By not allowing us to fill in his natural blanks with our natural plenty, he is, in effect, forcing us to experience his unpleasant chromatic and artistic limitations. And for every picture he makes, no matter what possibilities the individuality of the picture might have held. Which is just why his work has a pronounced monotony to it. With no light effects to speak of, his work stays flat in more than affect.

No one could accuse Fawcett of lacking integrity in his drawing, certainly. He was a master of a certain kind of academic accuracy. And the blocking of his scenarios is equally serviceable. But his lack of expressive juiciness and fixation on descriptors makes his art dry as a bone. Everything in his work drags on the eye like a cat's tongue on sandstone.

At the time he was working, his parched style was radical and new and influential. But like a lot of radicalism, in the long run one often finds that far more babies were thrown out than the state of the bathwater warranted. Every one of his pictures would have benefited from a brief period in the rain.

al mcluckie and Robert Cosgrove-- Thanks for your kind reactions. A large part of this process is to put the work of deserving, under appreciated artists back in front of the public. it's particularly gratifying when readers recognize and engage on the qualities of this work.

ReplyDeleteKev Ferrara-- I agree that Michelangelo's masterpiece (he was said to have spent 9 months picking out the marble alone) is superior to Fawcett's illustration, despite the Pieta's clear flaws. (I suspect that if Fawcett had two characters so far out of proportion you would've burned him for it here.)

As for some of your other points: I generally agree with you about Fawcett's use of color, and I don't cut him any slack for being born color blind. A number of artists (such as Peter de Seve) are color blind, although many of them have a heightened sense of value which helps them compensate, and others are great draftsmen. If the resulting art can't cut it they should find another line of work.

In answer to your question about whether admirable drawing is a worthy artistic goal, my answer is "yes."

As for your assertion that "his work has a pronounced monotony to it," I think the words you were looking for is a "distinctive style." Fawcett is a virtuoso of ink and line, with a broader range of marks on paper than Gibson, Coll, Flagg, Booth or any other pen and ink illustrator you might name. His opinions are so strong and his style is so virile (and sometimes arrogant) that it sometimes overwhelms his subject matter (which is why, for example, he could never compete with lesser artists such as Jon Whitcomb when it came to painting pretty girls in romance stories).

As for your parched vs. juicy dichotomy, I understand you have a genetic predisposition for shiny, wet looking colors; I admire Sorolla too. But there is a separate aesthetic out there, a god so ancient that it was old long before your oldest gods of oil paint were born. Many people (including you, apparently) have come to believe that "radical" means new and avant garde, but in fact radical means pertaining to the root or origin of things. You are unintentionally correct that Fawcett is "radical," in that the carved lines, scratches, gouges, drybrush, and other marks that make up the fossilized ink trail do indeed go back to the root of things. I promise, I like your symphonic embellishments too but those older gods have not lost their sway over me. Maybe it's a lizard brain thing.

I suspect that if Fawcett had two characters so far out of proportion you would've burned him for it here.

ReplyDeleteI overlook mimetic errors made in imaginative good faith all the time. In fact, if I don't see those errors, that's an immediate tell that the work lacks aesthetic imagination. (And, depending on the year, was probably photo-slaved.)

"In answer to your question about whether admirable drawing is a worthy artistic goal, my answer is "yes."

That wasn't what I was flagging. What I feel is that Fawcett wants me to admire his drawing more than he wants me to enjoy his illustrations.

As for your assertion that "his work has a pronounced monotony to it," I think the words you were looking for is a "distinctive style."

I find each picture monotonous on its own.

Fawcett is a virtuoso of ink and line, with a broader range of marks on paper than Gibson, Coll, Flagg, Booth or any other pen and ink illustrator you might name."

No doubt. However, that the implementation of a broad repertoire of descriptive marks can still result in deadly dull images is the deep point of about half of everything ever said about expression.

As for your parched vs. juicy dichotomy, I understand you have a genetic predisposition for shiny, wet looking colors

No, that wasn't the idea. I mean by "expressive juiciness" anything that will break the monotony of his obsessive discreteness, allowing for the imagination to enter the picture. That Fawcett's values have no resonance or graphic evocative power shows how monomaniacally fixated he was on the one burrow he knew how to dig. It's like he never learned that among the basics, there was more to it than where his talents naturally led.

Like Kev, David, i can't really fault Fawcett on a technical level. Even the washed out colours and muted values don't bother me. The main problem for me is that i can feel the presence of the photo ref too clearly (but that's my criticism of a lot of '50s-'70s illustration too). That, coupled with the fact that the figures are usually too perfectly arranged, and the acting a bit wooden (in a TV melodrama kind of way) lends the whole thing an air of staginess.

ReplyDeleteThere's a whole separate discussion here - which will take too long to go into now - about different types of 'artifice' and how one artist can make the most ridiculously, stylised confection seem utterly believable, while another labours away trying to create 'realism' and it falls flat. In short; the difference between good and bad artifice.

Notice that my problem is with how he dramatises a scene, and brings it to life (or doesn't), rather than anything to do with surface mark making.

Great exchange between David and Kev - thanks guys.

ReplyDeleteI think Fawcett's 'dullness' (in all its aspects) is largely a consequence of his weakness in realising images as forms fluxed in depth. Awareness of space/depth/proximity (and the poetry to be mined thereof) is, I believe, one of the senses most important to the vivification of an image.

Kev Ferrara-- It seems to me that our difference of opinion about Fawcett echoes previous differences about Dubuffet, prehistoric art, Morris Louis, tribal art, Burri, Rothko and abstract art in general (despite the fact that many of these other artists reside on the opposite side of the solar system from Fawcett).

ReplyDeleteI suspect the unifying difference is that I'm willing to assign more value to surface elements such as abstract design, while you require an artist to orchestrate a symphony of different elements into some kind of poetic distillation for the purpose of communicating content about something. (And by that you mean content other than "this is the color red.") Woe unto the artist, or the culture, or nation or generation that omits an ingredient from your recipe for high art (although I suspect most of the art from most of the globe for most of human history would not fit in your straight jacket). I treasure Sorolla and Sargent but I would not limit myself to an exclusive diet of their work, nor would I grade the rich multiplicity of art on the strict criteria of a relatively recent western painting tradition. It's possible to experience excellence in classical music and still appreciate excellence in jazz or blues or rock. Applying different criteria to different kinds of art doesn't require us to give up standards altogether, it just requires us to be more open minded and receptive about which standards apply.

The fact that you describe Fawcett as "a master of a certain kind of academic accuracy" and characterize his work as "academic life drawings" suggests to me that you haven't settled upon the criteria to apply to what he does. Academic accuracy is Pierre-Paul Prud’hon, and it never appealed to Fawcett; he was quite outspoken in criticizing peers who took that path. I'd call "academic accuracy" a gross mischaracterization of this kind of drawing.

One thing we do agree about is what you call Fawcett's "obsessive descriptive compulsions." Not on all of his work, but several of his major pieces have a dense, coruscating look and I would say that "obsessive" is not an inappropriate adjective. The only difference is that in these drawings I don't view it as a fault.

(CONT.)

Kev Ferrara-- Our exchange on Fawcett reminds me of the exchange between Andy Warhol and Albert Dorne:

ReplyDeleteWARHOL: "Art must transcend mere drawing."

DORNE: "Andy, there's nothing all that fucking 'mere' about drawing"

Laurence John-- I think your point about "different types of 'artifice' " is extremely important, and one we haven't considered around here. I think there is a good argument that a painting by Bouguereau, which goes to extremes to create the illusion of 3D reality, contains more artifice than an abstract painting which has no such pretensions and tries to fool no one about what it is. Getting closer to the middle of the spectrum, Fawcett is less interested in illusion than Sargent-- he doesn't carefully replicate skin colors, he doesn't capture light and perspective, he makes intense whorls and black and white designs. Which contains more artifice?

chris bennett-- the same point could be made about "vivification of an image." Would you say that a Franz Kline painting is pretty damn "vivid"?

Kev Ferrara, Laurence John, chris bennett-- Sorry guys, I tried to attach examples of Fawcett's work to illustrate some points in my last answers and failed miserably. Apologies for my technical incompetence; the best I can do is offer you a couple of urls to blog posts where I've reproduced the same images before:

ReplyDeletehttps://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2009/04/one-lovely-drawing-part-24.html

https://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2013/03/warring-with-trolls-part-2.html

https://illustrationart.blogspot.com/search?q=fawcett&updated-max=2012-09-28T05:26:00-04:00&max-results=20&start=6&by-date=false

One of these days I'll learn how to use this here internet machine.

David: "Fawcett is less interested in illusion than Sargent-- he doesn't carefully replicate skin colors, he doesn't capture light and perspective, he makes intense whorls and black and white designs. Which contains more artifice?"

ReplyDeleteDavid, you've listed visual properties turned into abstract surface marks, but that's not where my problem with Fawcett's work resides (he excels on the technical / abstract mark making level). Where he falls down is in the staging, composing, acting etc.

If you aim to re-stage reality (with people looking and acting as people look and act, as Fawcett is doing) it can glare when anything is slightly 'off' and feel 'artificial' or 'stagey' ('bad artifice').

Whereas if you build a cartoon world which has its own rules (e.g. Herriman's Krazy Kat), or stylise reality enough that it no longer aims to fool you that what you're looking at is 'realism' (e.g. Cuneo, Jorge Gonzalez, Ralph Barton, John Held etc.) then it can be imaginatively easier to enter the image ('good artifice').

p.s. I got into all of this after hearing about the 'uncanny valley' effect, years ago when i worked in animation. Then i realised it applied to realism in painting too; paintings that attempt a high level of 'realism' but the figures look like waxworks. Then i realised it applied to 'dramatic staging' too; paintings (or films) that attempt to be realistically staged, but fail to convince for various reasons. The uncanny valley turned into a minefield.

David: the same point could be made about "vivification of an image." Would you say that a Franz Kline painting is pretty damn "vivid"?

ReplyDeleteYes, indeed. Very much so. I mean 'vivid' as in a strong sense of presence. But it depends on what is being made more vivid or present. A strong design will possess this quality (which is amped up by making it bigger), but because it does not refer to anything outside of itself, this quality becomes one of charisma without content.

With images representing something other than themselves (say, a painting/drawing of violin on a wall), the job of giving them presence is, by definition, contrary to this very condition. As you've no doubt guessed, my example of the violin painting begs the question of how Kev's objections to Fawcett's deadening literalism are any different from criticisms of trompe l'oeil. In other words: in what way is a strong sense of presence in representational art distinct from the literalism of mimetic rendering?

Kev has already supplied the answer to this in stating how suggestion (in all its forms, not just rendering) is the prime mover of aesthetic content. I tend to think of 'suggestion' as the abstracting fulcrum on which poetry and literalism are balanced. But I'm in danger of misinterpreting him and getting in the way of his reply to you, which, I'm sure, will cover these things far better than I.

Thanks Laurence you make a good point. (And one which, I'd say, it is obliquely related to the question of presence.)

ReplyDeleteFawcett is less interested in illusion than Sargent-- he doesn't carefully replicate skin colors, he doesn't capture light and perspective, he makes intense whorls and black and white designs. Which contains more artifice?

ReplyDeleteSounds like somebody has never noticed that Sargent is far more abstract than Fawcett.

Anyway, Fawcett's inky descriptiveness is attempting to do the same basic thing as Sargent's painterly suggestiveness. Except with less success. The amount of 'artifice' involved is basically the same. Which is to say, if you want to say any semblance of memesis or reference is artifice, they are both nothing but artifice. And the same could be said of books and films and plays. They should have nothing to do with reality, if they are to be "pure" according to the high priest of the authentic Mr. David Apatoff. (see, two can play at this dumb game.)

Regarding Dorne… Albert Dorne actually felt his drawing, which is how he was able to both make it so expressive, and construct it so evocatively. Fawcett isn’t in his league.

I don't have time for a big long reply to everything. But here's something...

1/2

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteLet’s start with one basic idea, so we have some agreement to build on.

ReplyDeleteA hole in a carpet is formed by the carpet surrounding that hole. A window’s view is formed by its frame. When we speak of these things, a hole, a window, we are speaking of something which isn’t, not of something that is. And we only understand each by virtue of that which forms the void. This is the nature of suggestion.

Suggestion is a deliberately-formed implication gap. It is a purposeful void in the weave, where sufficient information is absent, but yet, that gap or interval – what is missing and where - is informed nonetheless. And it is informed by that which surrounds and forms it. It is a window frame, where the frame itself, through suggestive information, evokes to the mind the view within it.

In art, the nature of that imaginative/implicative gap (what would be there if what is not there were instead actually, somehow, there) is located in conceptual space, identified as a reference, and formed on the pictorial surface by virtue of the way that that gap has been notated into being; by its immediate local context, as well as by any larger context necessary to its understanding.

The simplest version of this in art can be found in the consideration of lost edges. This Zhaoming Wu charcoal portrait has many poetic lost edges. And it is the found edges that notate into being its lost edges, the “found” extant descriptors that notate into being the nature of the lost nonexistent descriptions. So the head feels solid, even when there is often nothing there in the rendering to describe the head’s contour or its sculptural form or its hardness. This bit of magic is happening by virtue of the notations that form around the lost information, the described head tells us of, implies or evokes to the imagination, the absent head information. Unless there is sufficient extant information, the lost information cannot be recovered by the imagination.

In the above paragraphs, I’ve done my best to describe the basic structure of suggestion. There are many dozens, perhaps hundreds of different kinds of suggestions in art aside from the lost edge. Each of which has a similar basic structure to what I’ve described, but each of which also has unique aspects.

2/2 (edited since original post)

Kev: "The amount of 'artifice' involved is basically the same. Which is to say, if you want to say any semblance of mimesis or reference is artifice, they are both nothing but artifice"

ReplyDeleteThis is my fault for bringing up artifice. I said to David in my comment above that I'm not using the word to mean mimetic rendering. I'm talking about dramatic staging, and varied attempts at 'realism'. And how some fail at that.

Of course, all paintings and drawings are 'artifice' if we simply mean 'illusion'... fooling us into perceiving 3D space where there is none. But that's not the way I'm using it.

Thanks Kev.

ReplyDeleteI'll just add a little if I may.

I believe the vividness, sense of presence or actuality given off by the Zhaoming Wu drawing comes entirely from its suggestiveness, a large part of which is the lost and found principle you have so well described.

The literalism of trompe l'oeil paintings means they can only really fool the eye when depicting a very shallow space. With an artful image our subconscious reading of its suggestive elements means they are coercing us to imaginatively 'fill in' or supply the missing special sense given to us by binocular vision, changing position (be it subtle or profound) and past experience in relationship to things visually apprehended.

I'm talking about dramatic staging, and varied attempts at 'realism'. And how some fail at that.

ReplyDeleteI agree with your insight about the uncanny valley principle applying to realistic blocking. I'd never thought about it that way.

However, I would add that one big reason that over-describing is such bad illustrative poetry is because it freezes action. Thus, Fawcett's figures aren't simply stiff because they are melodramatically clunky, they are also stiff (and undramatic) because they have been frozen, permanently knitted into place by relentless description.

I also take Chris' point that his figures don't really express through spatial depth. This was what I meant when I wrote earlier that "With no light effects to speak of, his work stays flat in more than affect." A lack of believable light effect actually causes flatness.

Laurence John-- I agree with Kev that your "uncanny valley" analogy introduces a very helpful concept here. So many artists work hard for realism, and may even get 95% of the way there, only to expire in the dreaded uncanny valley. The horrifying 5% that doesn't work leaves them so far short they might as well not have tried to go at all. So they try to salvage the 95% for which they slaved, through gimmicks like heavy shadows to conceal their inadequate parts, or distracting lighting effects, or poses which hide faces or hands that don't quite work. Those tactics can preserve the benefit of the doubt for a picture or two, but ultimately the artist's weaknesses reveal themselves.

ReplyDeleteI think the uncanny valley applies far more to realism in faces than to staging, because a near miss in faces looks affirmatively creepy and unnerving to us-- those facial expressions that make you think of a dangerous mental patient or a pod creature from Invasion of the Body Snatchers-- while a near miss in staging often just looks clumsy and amateurish, not threatening.

Fawcett was capable of doing highly representational work but after the first few years of his career rarely attempted to go there. In fact, pictures that looked photo-representational on the surface (such as his Sherlock Holmes series) quickly disintegrated into the craziness of sub-atomic particles when you took a closer look. Fawcett obnoxiously upbraided students and even his peers for polishing and polishing their images in order to achieve a dazzling likeness. He urged them to reconsider their goals. But when it came to staging, he was widely respected as a master of British understatement, employing a tilted head or a raised eyebrow where his American born peers would use an explosion or a splash of scarlet to affect the dynamic of a picture. I would not say that the two illustrations here are the best example of that, but if you read his book on The Art of Drawing or his materials for the Famous Artists School, you will see that he was quite eloquent on the staging qualities being discussed here. I think at some point he decided he had other fish to fry.

chris bennett wrote: "because it does not refer to anything outside of itself, this quality becomes one of charisma without content."

This is a point I've waltzed around with Kev on, and I'm not sure there is a place for a meeting of the minds. Kev has yet to show me a picture that totally "does not refer to anything outside of itself" because I think that the color blue can refer to something outside of itself, just as a vertical stripe can refer to something outside of itself. As long as we are psychologically complex human beings who process data subliminally and think in analogy and metaphor, I don't see how even an abstract painting can be quite without content. Obviously this doesn't satisfy Mr. Ferrara's notion of content. I also believe that while there is much to be gained from spending hours poring over the layered iconography and symbolism of a precious Van Eyck, there is also much to be gained from a huge red Rothko painting over your shoulder adding warmth, solemnity and depth to the tone of a room, (or a wall sized action painting by Kline or Gottlieb painting shaking up your metabolism). I understand that these last examples of content fail some people's legislative definition of "art." I'm saying that's OK.

I agree with you these latter examples do have "charisma" (which as you know comes from the Greek word for "blessing" and refers to a divinely conferred gift or power.) We could discuss whether their charisma is "without content" as discussed in the preceding paragraph, or I could save us all time by asking, "who says that a blessing without a specific narrative content necessarily fails as art?"

David:" ... while a near miss in staging often just looks clumsy and amateurish, not threatening"

ReplyDeleteTo be clear: i wasn't implying that bad staging felt creepy. Just that the 'off' feeling was analogous. Rather than the creepy feeling you get when you see a human but not quite human painting or CG model, the feeling (in the case of staging and acting) is more 'this doesn't feel realistic' or 'this feels wooden'.

David: "But when it came to staging, he was widely respected as a master of British understatement..."

I can see that, but i also see a theatrical stiffness in the overly formal, overly precise blocking, which could equally be the result of a British theatrical vein.

On the Uncanny Valley analogy...

ReplyDeleteThe 'uncanny valley' is a dip in a curve, that represents a sudden decline in comfort as cgi nears mimetic fidelity. There is some research to back up this dip. Though I'm not sure the model of pictorial experience used was all that sophisticated. But there is certainly a truth in there somewhere. It has been said that the dip in comfort relates to the discomfort in recognizing mental disability. Probably physical disability as well; the stiffness of parkinson's, old age, facial paralysis, or the frozen corpse, and so on. Even the strange feeling we get from one of those stiff plastic halloween masks might relate to the effect.

(It is worth thinking of this in a wider way through something Howard Pyle said; "The better your picture, the more a little error calls attention to itself. As a single pebble in an otherwise comfortable shoe will quickly call attention to itself.")

Getting back to Laurence's analogy, I think we can walk it back to something else he pointed out earlier; which is the photo dependency. I think the connection here is that photography is so unnatural in the stiff, inexpressive, non-compositional way it freezes reality that allowing it to unduly influence a work of art will inevitably result in its unnaturality being transferred to canvas. Life is change, life is movement. There is no truth in a frozen instant, only fact. Having said that, I think photography can do well capturing the story of an interesting face. Because a face can contain a full story on its own. But it must be one heck of a face, and the credit for the photo goes to the face, not the finger pressing the shutter down.

With gesture and action, the problem is shown more plainly; the frozen instant captured by a camera is akin to the frozen mask-like face. There is some uncanny about it, literally.

*There is something uncanny about it, literally. (Sometimes that pebble in a shoe is a single syllable.)

ReplyDeleteKev has yet to show me a picture that totally "does not refer to anything outside of itself" ... As long as we are psychologically complex human beings who process data subliminally and think in analogy and metaphor, I don't see how even an abstract painting can be quite without content. Obviously this doesn't satisfy Mr. Ferrara's notion of content.

ReplyDeleteThis is a dire paraphrase of my arguments. I have clearly done a poor job explaining my points.

We’ve never had a deep discussion on here about the nature of “content.”

As with everything I am interested in the qualitative hierarchy of visual content, in order to get to the high end and see what makes it tick.

At the low end of the spectrum (literally), yes, you can say a red wall has content. You can say excellent performative crying indistinct from real crying has content. You can say passing gas during a staff meeting may have content (I mean symbolic content; hopefully nothing more than that.)

The issue in the above cases is that the proffered ‘content’ is dead simple. It is so simple in fact, so basic, that in each case, we may not even be dealing with communicative intent at all. The red wall may have been painted by kelp, butchery, or oxidation, the crying may be real or caused by brain damage, the gas a purely accidental emission. And without communicative intent, I don’t think we are talking about ‘content’ in the sense that we mean it.

And if we can’t tell purposeful signification from random sign-like phenomenon, are we even talking about Art? Let alone Art worth talking about? Why are we bothering? Let's be blunt: If somebody says a Geode slice is ‘a work of art’ they’re a hack interior decorator, and don’t really belong in a philosophical conversation. Nor do collectors of corkscrew Akro Agates belong in the same conversation. For it takes no talent whatsoever to choose among a favorite result of a random form-generating process.

Calling collectors of found objects 'artists' is like saying that the couple that picks out floor tiles, wallpaper, and drapes from the stock available at Home Depot are 'artists.'

If a creator purposefully makes their own geode-slice or corkscrew agate looking painting, this is the same as making your own tile, wallpaper or drape pattern. That is what we call design. It doesn't matter if the pattern is hung on the wall or glued to the wall. A frame merely concentrates interest, it doesn't transform the content within it by some magic means.

There is no need to compare applied designs or fabric swatches to a painting by Harry Watson. Calling what Harry Watson does 'design' denigrates his work, and destroys the basic conceptual distinction between applied design and Art.

In communication, complexity and its structure matters. It keeps us from floundering around with uninteresting edge cases, giving credence to the sophists, pretenders and fakers. Saying design and art are the same is the opposite of saying something useful.

Kev wrote

ReplyDelete“Because a face can contain a full story on its own. But it must be one heck of a face, and the credit for the photo goes to the face, not the finger pressing the shutter down.”

http://philippehalsman.com/?image=the-frenchman

The qualitative and structural features of Art that make it more advanced than Applied Design are the same qualitative and structural features that make thought more advanced than mood. That’s the simplest way I can put it.

ReplyDeleteRegarding reference: We've discussed for years on this blog the probability that there is no such thing as wholly non-referential art. I’ve said that Jackson Pollock's work resembles what happens when a car speeds through a mud puddle. We've talked of patchwork art looking like an aerial map. We’ve discussed how any random arrangement of form becomes a projection test, where one can, with a modicum of imagination and suggestibility, ‘see’ similarities to the world. And so on. Nobody’s arguing for art purified of reference (except pretentious graphic designers of the high modernist stripe.)

ReplyDeleteThe distinction of interest with respect to reference is between Art and Writing. What makes Art different than Writing is the dependence of the latter on ready-made references to convey essential meanings.

References require inspection, decoding, and recall. A clever heuristic for determining how meaning is communicated in a painting or drawing, is to note how quickly one segues from experiencing the picture (being in the stunned state of aesthetic arrest) to inspecting the picture in order to understand it.

It is literature’s basic nature as a mode of communication that its code must be inspected in order to be understood. Which is why nobody looks at a page of text from a distance and thinks they understand it. The meaning of the page cannot be intuited aesthetically. It must be decoded. The page is not the canvas literature paints on, nor is the paragraph shape. The words are chosen, not created.

Everything in Art, conversely, is created from scratch. Thus there is a tremendous amount of freedom in how meaning is conveyed. This allows imaginative gaps to be opened up everywhere and between anything, including within the references. And in these gaps within the references (and without them), the essential meanings of the references may be expressed to the imagination directly by the orchestration of sensual forces. Thus, the references themselves don’t actually require recall in order to be understood. This is the sense in which great art creates its own reality.

This is a difficult concept, so I’ll put it another way. It is easy to think of depiction in art as mere illusion. But there is a distinction between the illusion as trick (Trompe L’Oeil, Op Art) and what is going with illusions in greater Art. Depiction in great art is actually only the illusion of depiction-as-reference. What is actually being depicted is the suggestively meaningful forces that sensually define the meaning of the references. Thus we understand the references sufficiently through aesthetic apprehension to understand the image. This is why Harvey Dunn said ‘A picture is its own definition.’

Beyond the period of aesthetic arrest, once the Art spell loses its power over the viewer, the meaning-broadcasting deed has already been done. And one is free to read the references in a word-like way and recall associations at whim.

David: "who says that a blessing without a specific narrative content necessarily fails as art?"

ReplyDeleteIs a rose a work of art? Is a thoroughbred at full gallop? Or a flawlessly plastered wall? The arrival of spring? Nicole Kidman's body? A Tiger Wood eagle at Augusta? A large rectangle of dark reddish cloth hanging on a metropolitan gallery wall? (or a highly enlarged single comic panel saying "I know how you feel Brad")

All have their own gush of charisma. To say this alone qualifies these things as art is the same as saying all that glisters is gold.

But every one of these examples do have a specific narrative content to them. The question is whether an authored narrative structure qualifies, or fails, as art.

ReplyDeleteDavid wrote

ReplyDelete“One result of Fawcett's continuing commitment to observation is that when he illustrated a figure, he was not content with the usual simplistic shortcuts: symmetrical people standing perpendicular to the ground. ‘ Instead, he observed that people are often bent or lopsided, reflecting life's tug of war between gravity and organic matter:”

Maybe your not being critical of symmetry David but it sounds like art school talk where a prowerful organizing principal gets knock down as being old fashion and boring by people who can not do what they are criticizing . Or when modern critics try to make modern art sound innovative and revolutionary by rejecting the values of the past. Bad figure drawing is not symmetry’s fault. In fact understanding symmetry makes good figure drawing possible.The human body’s arrangement to gravity could be a “tug of war,” but more then likely it reflects how nature harmonizes and creates beautiful arrangements when different forces come into relation with each other. The “war,” analogy has little to do with art. One can just as easily say gravity’s our friend because it anchors and supports us and harmonizes by relating all things to one point, the center of the earth

The principle of symmetry is felt throughout Fawcett’s compositions in doorways, aisles ways, the church windows chairs and floors.The man made environment of rooms made up of horizontals masses and verticals masses is the perfect contrast to the rhythm of organic matter and the emotional responses of the human body and this staging focuses the viewer on the human drama at hand which is the point of the illustrations. They may feel artificial and not “realistic, or believable,” but most older entertainment feels the same. I like how readable they are as one element in the pictures leads the eye to another. From the hat in the foreground, to the horizontal body in death contrasted with the two vertical figures. Form which the eye rises with the ‘calm and puzzled,’ detective’s arm and continues up to the woman’s body framed by the doorway and finally too her apprehensive and worried face which directs the eye us back to the beginning of our journey. It’s clearly, “staged,” in an old fashion way but it is also comprehensible, in art things should be clear and understandable, especially when you may only have the viewers attention for a short amount of time. When they are not frustrations arises in the viewer.

David also wrote,

“ (I suspect that if Fawcett had two characters so far out of proportion you would've burned him for it here.)”

I’ve seen that sculpture a lot and I never once thought of it being out of proportion. It bypasses such responses. Michelangelo obviously love the rhythm of form in and of itself and would have considered any failure of clear expression of the individual forms that make up the body a failure on the part of the artist. One only has to read about his response to Titian’s paintings. So much of art has to do with what an artist wants to say about reality, it is the reason he picks up his pencil in the first place and this primal intention gives the work its form. Not understanding that simple intention is what leads to muddled and confused works. One may love mystery while another loves clarity.

I agree with you these latter examples do have "charisma" (which as you know comes from the Greek word for "blessing" and refers to a divinely conferred gift or power.)

ReplyDeleteI did not know the origin of the word.

However, that Charisma is a 'divinely conferred blessing' is a point about the origin of the word in Greek culture. It is not really an explanation of the actual phenomena of Charisma, in people or Art.

A very interesting technical discussion could be had about what causes the sensation of Charisma in people and Art; what causes that property to emerge? Because, no doubt, all great Art has Charisma.

Etymonline.com is one of my favorite site on the net and it is worth looking up the word there.

Thanks for the link Kev.

ReplyDeleteAnd for flagging up David's somewhat cheeky etymological tactics to foil my argument. :)

I am of course using the word charisma in its colloquial sense as described in Etymonline: Meaning "gift of leadership, power of authority" is from c. 1930, from German, used in this sense by Max Weber (1864-1920) in "Wirtschaft u. Gesellschaft" (1922). More mundane sense of "personal charm" recorded by 1959.

“ Beyond the period of aesthetic arrest, once the Art spell loses its power over the viewer, the meaning-broadcasting deed has already been done. And one is free to read the references in a word-like way and recall associations at whim”

ReplyDeleteWhile I agree largely with the thrust of your argument, I think you’ve undersold the art of poetry and literature.

Writing, when done well, when done truly poetically, also has stages of “aesthetic arrest” followed by a solidification into literalism.

If writing today fails to provide these phases, that says more to me about how modernist criticism has ruined writing than does it illustrate a categorical difference in the way the forms function.

Writing today has an awful lot in common with anime, and it seems to me that you’ve mistaken this modern codification of ready-made easily-consumed symbolic language for the whole of language’s possibilities as an art form.

Richard,

ReplyDeleteI don't disagree with you that great writing has its own kinds of wondrous poetic experience/"aesthetic arrest." How that works is a whole other can of worms with interesting parallels and differences to Art. But I think things could get wildly off track here if I started getting into the poetics of writing instead of sticking to Art. (Which is what I would need to do in order to effort to explain all the similarities.)

My point is to get at what it is about Art that makes it unique. As I believe the definition of anything is therein.

Best wishes.

Kev Ferrara wrote: "The qualitative and structural features of Art that make it more advanced than Applied Design are the same qualitative and structural features that make thought more advanced than mood. That’s the simplest way I can put it."

ReplyDeleteWell, don't you kind of beg the question by labeling a substantial percentage of what the world calls art (for example, Rothko, Olitski Morris Louis, Ellsworth Kelly and others we've discussed here) as Applied Design rather than Art? Aren't you simply defining away any serious consideration of the underlying issue?

Putting that aside, the even more interesting and substantial issue raised by your comment is why you believe thought is necessarily "more advanced than mood." I know that was formerly the central faith of the age of reason. It took a long time for observant, principled people to surrender that faith, and then only reluctantly and gradually, over many decades after they recognized in the 20th century where our magnificent rationalist delusion had delivered us: the inventions of mass transportation that accelerated the delivery of troops to the front in World War I and accelerated the delivery of victims to the death camps in World War II. All the science and technology that was turned into aerial warfare, new kinds of bombs, poison gas, tanks, machine guns, enhanced slaughter of highly literate and cultured Germans and Brits. Some of the most "thoughtful" writers and poets of the 1920s and 30s-- Bertrand Russell, Auden, Spender, Gide, Isherwood, Brecht, etc. rationalized communism as a "ruthless force from which a new and juster order might emerge."

It took the 20th century shock to our system for art to take what you consider a wrong turn when it concluded, "thought has betrayed us and brought us someplace horribly wrong; maybe Dada and surrealism and demoiselles d'avignon and other schools of nonrational disconnective art are an appropriate response to the cracked domain of reason. "

I note that some of the greatest artists recognized this point earlier. Goethe-- the poster boy for thoughtfulness, a legendary scientist, statesman, author, poet and man of letters, a flower of civilization by anyone's standard-- wrote, "The shudder of awe is humanity's highest faculty." Dostoevsky showed us where Raskolnikov's thinking led him, then admonished, "man, man, one cannot live quite without pity."

For me, regardless of whether you label art thought or mood, the ultimate determinant is always quality; a profound mood makes for better art than an unsubstantial thought. (I've previously quoted the art superstar Tracey Emin here, who shared her technique for creativity: "I like to lie in bed in the morning for an hour just thinking, thinking thoughts. And that's one of my favorite things to do." Perhaps you believe her thoughts are more advanced than mood. My answer, as usual, is the unsatisfying "it depends." )

I'm not blind to the risks of celebrating art based on "a shudder of awe," and I do think we always have to be thoughtful and responsible about understanding why we like what we like, but I think there is a countervailing danger in never venturing out from your fortress to examine new and strange art forms.

Regardless of whether you label art thought or mood, the ultimate determinant is always quality

ReplyDeleteYou are confusing the issue. "Quality" is the answer to the question, "what kind of cultural or decorative products do you want in your life, in your house, and in your mind?" And the answer to that is, "Good ones that please me and the people around me and make my life nicer." This translates, I would say, to "I would like nice products of all types in my life, rather than junk or ugliness." So you want a quality kitchen lamp, a quality rug, and quality plumbing fixtures just as much as you want quality designs and quality Art. Yes, everything contributes. You want your home and life to have a pleasant mood that suits you. Fine. But that's a different question.

In other words, since there are many more "blessings" to purchase and consume in life than just Art, it cannot be that Art's definition is "a blessing."

Well, don't you kind of beg the question by labeling a substantial percentage of what the world calls art (for example, Rothko, Olitski Morris Louis, Ellsworth Kelly and others we've discussed here) as Applied Design rather than Art? Aren't you simply defining away any serious consideration of the underlying issue?

That is the underlying issue. The conflation and distortion of meanings to smear and confuse distinctions in order to tear down artists and elevate designers.

The reasons are manifold and predictable; money, marketing, politics, populism. And, of course, it is a hell of a lot easier to make Designs than Art. So it is cheaper to produce. Easier to make them wall size too, because size impresses. And with all that time saved in the studio, there's more than enough time to sell it by the mouth, program hype-men from key periodicals with pretend theory, and create selling networks and scam operations to bilk rich people or create "investment opportunities" for them and advocate for beneficial Tax write-offs. All of which goes to exactly why it goes without saying that "a substantial percentage of the world" is ignorant of even the existence of an issue.

It took a long time for observant, principled people to surrender that faith...

ReplyDeleteThis sentence is not an argument as far as I can tell. Rather, it is bald "perfuming of the well" in which you plan to bathe.

...and then only reluctantly and gradually, over many decades after they recognized in the 20th century where our magnificent rationalist delusion had delivered us: the inventions of mass transportation that accelerated the delivery of troops to the front in World War I and accelerated the delivery of victims to the death camps in World War II.

Absurdly tendentious. This is a purely socio-political hair-on-fire associative way of considering the issue. This has nothing to do with Art or aesthetics. This kind of 'thinking' is exactly why thinking, rather than emotion, is superior. Emotionalism belongs to early motherhood, where first-order thinking suffices. Everywhere else, the unintended consequences of emotionalism become overwhelming.

I'm not blind to the risks of celebrating art based on "a shudder of awe,"

I don't grant your association of the "shudder of awe" to mood over thought. As far as I can tell, technically, there are only sensations in the brain. Sensations are what comprises all of our experience. Mood is, by nature, sensation in harmony without much in the way of drama. While thought contains the same sensations of mood, the same sensations of mind, but orchestrated and organized to (hopefully) create a narrative expression of truth.

2/2

David—Your statements regarding Fawcett's work—especially in reply to Ken Ferrara’s comments—have been magnificent.

ReplyDeleteI grew up admiring and studying RF’s work. I believe Fawcett’s work is best appreciated when considering his draftsmanship. He was a master at dramatic illustration and composition. However his drawing is what sets him apart. I loved to study is preliminary work.

His book “On the Art of Drawing” reveals much of his unique talent. In that book, is his drawing “Lincoln at Gettysburg”, one of the best illustrations of his career.

David: "As long as we are psychologically complex human beings who process data subliminally and think in analogy and metaphor, I don't see how even an abstract painting can be quite without content"

ReplyDeleteSurely that would be a failure on the part of many abstract and minimalist painters, since they were explicitly trying to make work devoid of content and representation, that referred only to its own physicality ?

David: "Obviously this doesn't satisfy Mr. Ferrara's notion of content"

But you're seeing content where there shouldn't be any. That can only mean that either the work has failed in being devoid of outside reference, or you're reading it wrong (seeing too much into it).

(i'm talking about 'hard-edged' types, not some of the abstract expressionists, who did permit some gestural vague emotion)

chris bennett asks: "Is a rose a work of art?"

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you're continuing our tradition of not shrinking from the big questions. Is a rose a work of art? Well, if you're a member of the American Rose Society who cultivates and crafts a rose "to improve its standard of excellence," I'd guess your answer is yes. If you're one of those who believes that a conscious god or mother nature designed the rose, I'd guess your answer is yes. If you're Edward Steichen in the early days of photography, using the new medium to convey the beauty of heavy roses, the answer is "maybe." Different people may have different notions of what it takes for beauty to be "authored." I may have more requirements than most for a heavy handed, conscious "authorship" but not, apparently, as many as you or Kev.

If I find a piece of driftwood that reminds me of an upside down face and I pick it up, turn it upside down and put it on a pedestal at a jaunty angle, its facial expression could well have more "narrative content" than another artist's sculpture made from scratch. ( https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.collageplatform.com.prod/image_cache/1010x580_fit/559650f9cfaf34ff158b4568/7e45d97ed3b9ff79b67cac4b0c885067.jpeg ). If so, why doesn't that count as a "narrative structure" to satisfy your definition? And why don't my conscious actions qualify as authorship?

Tom-- I suppose my point is that symmetry is fine for an initial, rebuttable presumption about the human form, and we might even stop right there if we're drawing idealized people for a Flash Gordon comic strip, but if our goal is to pay attention and depict people as they truly are, that initial presumption is often rebutted by accurate observation. Bodies and even faces are often asymmetrical. My point about gravity was simply a reminder that our depictions of the body tend to be more insightful if we understand what causes bone and muscle to sag with the passing years

I do agree with you completely that "The principle of symmetry is felt throughout Fawcett’s compositions in doorways, aisles ways, the church windows chairs and floors.The man made environment of rooms made up of horizontals masses and verticals masses is the perfect contrast to the rhythm of organic matter and the emotional responses of the human body and this staging focuses the viewer on the human drama at hand which is the point of the illustrations." I think that's a large part of why Fawcett puts those man made perpendicular and parallel masses in, to highlight the asymmetry of the organic forms.

Tom also writes: "I’ve seen that sculpture a lot and I never once thought of it being out of proportion. It bypasses such responses." Yes, but now that it is pointed out to you, you see that Mary is a giantess, don't you? It's quite possible that people don't notice because of Michelangelo's overwhelming artistry but I think it's at least equally possible that people don't notice because star struck audiences have stopped looking.

If I find a piece of driftwood that reminds me of an upside down face and I pick it up, turn it upside down and put it on a pedestal at a jaunty angle, its facial expression could well have more "narrative content" than another artist's sculpture made from scratch. ...If so, why doesn't that count as a "narrative structure" to satisfy your definition?

ReplyDeleteTo make more general the point I made earlier; all things encountered by us humans are automatically, unconsciously and necessarily supplied with a specific narrative content in order to contextualise them. The question is whether an authored narrative structure qualifies, or fails, as art.

And why don't my conscious actions qualify as authorship?

Your first 'conscious action', being a case of pareidolia, is, by definition, unconscious and, being a 'found object', is, by definition, not authored.

Your second conscious action, being to place it on a pedestal to 'best effect', contains narrative in that it is the consequence of wanting to claim the condition of art for something you have found. And you certainly 'authored these actions', but you were not the author of anything outside of that.

An Author that presents a factual narrative without ostensible interpretation is called a Journalist.

ReplyDeleteTo be an Artist/Author does not require the creation of the subject out of whole cloth. But it does require that the work be suffused with the author's narrative creativity. There must be structurally interpretative, creative manipulation and editing of the subject/narrative. Plus deft additions. All manifested through the sensually symbolic terms of the given medium in order to express an ulterior idea that goes beyond the facts or descriptions.

A rose is a product of nature and is not authored in any significant way by a human being, even if cultivated for certain qualities. To change the color of the rose or manipulate some aspect of its shape is design. To improve its health is botanical gardening.

If you find something on the ground, you didn't create it. If you saw a face in it, you didn't create that face. If you put it on a pedestal or a frame, congratulations, you're a postmodern genius.

David,

ReplyDeleteI think Kev adequately responded to the “errors” in Michelangelo’s Pieta, but since you brought it up again with Tom I’ll try to explain the intention of the design. The exaggerated size is not just some propaganda but represents the magnification of loss, the counter intuitive process by which obliterating loss magnifies the meaningful from the meaningless.

In our daily world, the annoying person magnifies our fallible human nature by demanding an expansion of our current levels of patience through understanding, thus the annoying person serves a sanctifying end by demanding we find the longer rather than the shorter solution.

It’s part of our fallible nature to seek perfection in pleasures, work and all matters and so universal is this drive that it’s a testament to perfection and perhaps this explains the clinging and near worship of architecture, design and digital achievements. What remains allusive is a perfection that reveals itself in the most complex of all human variables, or in everything. That is, a perfection capable of revealing itself to and satiating the core of our fallible beings.

Fawcett was seeking some level of perfection and in a group of images in a small book called “22 Artists and Illustrators and How They Work”, there are a handful of his images in black and white which have ample rhythm between light and dark and active and rest areas. Yet I have often felt it wasn’t easy to enter his illustrations for fear of knocking over some China, or bumping into some detail in the background forcing itself towards the foreground. For all the effort to create space, an overabundance of detail can have the affect of flattening out a picture and in the colored images it’s hard to deny such is happening.

A bunch of good observations above.

Sean

In a (probably vain) attempt to touch back to the original topic of this post, Robert Fawcett, I would just like to point out that Fawcett probably had the most traditional, old-fashioned training of any of the great mid century illustrators. He went through the rigorous instruction process at the Slade school in England where he was tortured through marathon drawing sessions under the watchful eye of humorless instructors.

ReplyDeleteDespite his traditional training, Fawcett loved "modern" art and was close personal friends with avant-garde British artists such as Henry Moore or the controversial Graham Sutherland. He spoke out often about the legitimacy of modern abstraction and the connection between abstraction and what he was doing in his drawings.

Perhaps as a result of his traditional training, Fawcett's draftsmanship was widely respected by the best illustrators of his generation. It is possible, as someone has suggested, that Dorne was better, but Dorne didn't seem to think so; neither did Parker or Briggs. I personally stood next to Bernie Fuchs as he closely studied an original Sherlock Holmes drawing by Fawcett and concluded, "Man, drawing just doesn't get any better than that." When Fawcett arrived at some of the monthly luncheons for illustrators at a local hotel in Westport Connecticut, a couple of the younger wags would half jokingly bow down before him. (It irritated the hell out of him.)

Popularity or the compliments of peers has never been definitive on this blog, but as long as we know what others were saying about Fawcett at the time, I think that is historically relevant.

Kev Ferrara, chris bennett, Laurence John-- We seem to be having a difference of opinion about just how purposeful and comprehensible the content of a picture must be in order for it to qualify as higher art. I confess I don't feel qualified to legislate how much specific purpose is necessary in order to constitute "art," but then I'm not yet convinced that you're qualified either,

ReplyDeleteKev seems to think that "in communication, complexity and its structure matters. It keeps us from floundering around with uninteresting edge cases." I seem to have a higher tolerance for floundering than Kev, or at least a greater willingness to waste my time on art that is potentially "interesting."

Kev further says that in order to get to the "high-end" of the "qualitative hierarchy of visual content," we shouldn't waste our time on "dead simple" content that lacks the requisite communicative intent. We must focus on "purposeful signification." Chris Bennett says that we should give little weight to the fact that "all things encountered by us humans are automatically, unconsciously and necessarily supplied with a specific narrative content," and should focus instead on whether the content was intentionally and consciously "authored" by its creator. Lawrence John worries that I'm reading too much into art that is intended to "refer only to its own physicality," thereby "seeing content where there shouldn't be any."

I agree that it is possible to go too far in the direction I'm describing, but it seems to me your position fails some key tests. Too much great art through history is created when the artist takes his or her hands off the controls and lets their subconscious play a role. Too much art is spoiled by the intentionality of artists who are uncomfortable with ambiguity. Too much important artistic invention comes from viewers meeting the artist halfway and playing a role in the communication process. I think many a muse would disagree with and even resent your prescription of the creative process.

Furthermore, at least a few of you have previously stated that an art object must stand alone, without a position paper or a back story explaining the intent of the artist. All of you seem unwilling to give Dubuffet any credit for finding that piece of driftwood and putting it in a museum at the right angle. OK, but I'd say that if we restrict our focus to the merits of the object itself, and ignore where the object came from, there is more sophisticated and interesting content to be gleaned from the face in Dubuffet's driftwood than in a face purposefully drawn by the third rate Burne Hogarth or 100 other artists we've discussed here. How do you resolve that contradiction?

Too much great art through history is created when the artist takes his or her hands off the controls and lets their subconscious play a role.

ReplyDeleteThis is possibly where the misunderstanding between us is stemming from. You seem to believe that what is meant by the 'authoring of art' is putting a heavy emphasis on the conscious process. As a practicing artist I can say that, in my experience, it most certainly does not.

Art is deeply directed in its realisation by the subconscious because the subconscious, unlike the linear function of conscious thinking, has the ability to synthesise large numbers of elements into a cohesive whole. So it is, in practice, the subconscious that is doing most of the heavy lifting and subtle lifting of the authoring process.

David,

ReplyDeleteDon't presume we are all making identical argument.

I do not make a distinction between conscious and unconscious creative work. Because I don't believe there is a distinction between the motives of the conscious and unconscious. I understand the consciousness as merely the (often mistranslating) messenger and librarian of the unconscious. There's a separation of duties, but not a split in being. I think we are always doing as a whole being. And any illusion of being a fraction of our total selves (a dissociated consciousness apart from the self) is an egoistic delusion caused by the chatty symbol-obsessed part of our minds trying to run the show.

In my view, only the end product of the art process is to be believed. Whatever is to be understood about the art is in the art itself. Everything else is irrelevant.

Too much art is spoiled by the intentionality of artists who are uncomfortable with ambiguity.

I thought you were here to champion Mr. Fawcett, not bury him?

Regardless, we've already had the argument about ambiguity and vagueness. About how on their own ambiguity and vagueness are just design, though they might also be working as Projection Ttests that people can Rorschach out to at will. But in a narrative context, the possibilities of some vague or ambiguous area are so narrowed, that suggestivity results. Context vivifies mystery; mystery alone is nothing. (Provided what is there doesn't tell against the narrowed possibilities caused by the context.)

Too much important artistic invention comes from viewers meeting the artist halfway and playing a role in the communication process.

Yes, this is called imaginative closure, which is just how one responds to suggestion. The artist provides the frame and the viewer adds the window.

If the viewer is providing the significant content entirely, then he is "meeting the artist" not halfway across the river, but at the other shore entirely. Where the artist is, no doubt, enjoying a nap.

OK, but I'd say that if we restrict our focus to the merits of the object itself, and ignore where the object came from, there is more sophisticated and interesting content to be gleaned from the face in Dubuffet's driftwood than in a face purposefully drawn by the third rate Burne Hogarth or 100 other artists we've discussed here. How do you resolve that contradiction?

I don't think there is any such thing as accidental symbolic content. That's a supernatural claim. And I don't think you are arguing that. Because I think what we mean by "content" is symbolic signfication. Yes?

Regarding Dubuffet's object itself, I've walked the woods my entire life. And I can confidently say, there isn't a single object in the entire forest that doesn't suggest a face somehow. Whether rotted stumps, mushroom configurations, blighted oaks, lichen-spotted rocks, breaks in boulders, tree-branch configurations, pebbles on a dirt mound, any group of leaves, the mountain ahead, patches of sky, and so on. Dubuffet found a good one, no doubt. But there's a billion good ones out there for anybody with half an imagination.

You seem to believe that what is meant by the 'authoring of art' is putting a heavy emphasis on the conscious process. As a practicing artist I can say that, in my experience, it most certainly does not.

ReplyDeleteArt is deeply directed in its realisation by the subconscious because the subconscious, unlike the linear function of conscious thinking, has the ability to synthesise large numbers of elements into a cohesive whole. So it is, in practice, the subconscious that is doing most of the heavy lifting and subtle lifting of the authoring process.

I obviously agree with this.

David: "Laurence John worries that I'm reading too much into art that is intended to "refer only to its own physicality," thereby "seeing content where there shouldn't be any."

ReplyDeletewasn't that one of the main objectives of much early abstraction and later minimalism according to its creators ? don't take my word for it, hear it from the horse's mouth:

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/abstract-art

quote (referring to Morris Louis): "Post-painterly abstraction (1950s): This form of abstraction focused more than ever before on the basic elements of painting: form, colour, texture, scale, composition and were ruthless in their rejection of mysticism and of any reference to the external world"

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/m/minimalism

...

Here's a scenario: A young painter in the 1950s decides to do some large abstract work. Something 'pure', which refers to nothing beyond its literal presence (he has read in a catalogue that this was the concern of important modern painting). One of the paintings in his first show is a large, wide rectangle with two (hard edged) vertical black stripes against a flat orange background, and a perfectly round circle in pale purple. A person attending the private view says "Oh i love this ! It reminds me of a view from my childhood; two telegraph poles and a setting sun". The artist rolls his eyes with contempt. Who is the joke on ? The viewer for being so unsophisticated that they couldn't understand the artistic intentions of the work. Or, the artist for not considering that the human brain will 'see things' in the most minimal composition ?

Laurence,

ReplyDeleteI believe Victor Pasmore, who became a convert to (almost) 'pure abstraction' after starting out in the Euston Road School's 'objective painting' camp, admitted later in life that what I believe he referred to it as 'the modernist experiment' (I can't find the quote itself) had failed.

Yet it is curious to see a contemporary artist of the first rank, Mark Shields, in the course of his career go from this: http://www.markshieldsartist.com/exhibitions/inhabitants_of_the_dream_courtyard.html

to this:

http://www.markshieldsartist.com/exhibitions/the_inaccessible_land.html

As far as my personal enjoyment of this great artist's work is concerned I believe this to be a self evident loss. I would be very interested to know if David sees it differently.

Chris Bennett wrote: "This is possibly where the misunderstanding between us is stemming from. You seem to believe that what is meant by the 'authoring of art' is putting a heavy emphasis on the conscious process. As a practicing artist I can say that, in my experience, it most certainly does not.

ReplyDeleteArt is deeply directed in its realisation by the subconscious because the subconscious, unlike the linear function of conscious thinking, has the ability to synthesise large numbers of elements into a cohesive whole. So it is, in practice, the subconscious that is doing most of the heavy lifting and subtle lifting of the authoring process."

Like Kev, I heartily agree with this. But then please explain to me where the misunderstanding comes from? A group of commenters seems to reject the subconscious "Rorschach Test" aspect of what Dubuffet saw in the driftwood on the beach and devalue the subliminal response of a viewer to the violence of a Franz Kline brush stroke. They don't seem to allow credit for the subconscious connotations of erecting the monoliths at Stonehenge or Barnett Newman's bold vertical stripe in an immense blank field. Instead, they want to see conscious "authoring" and "purposeful signification" and "communicative intent." As far as I can tell, this demands a level of control that leaves little room for the subconscious or the happy accident. The inference I drew from this chain of comments is that true art requires a firm hand in control of the brush, executing a deliberate message. Bouguereau, never Kandinsky.

If, as Chris says, 'authoring of art' does not put a heavy emphasis on the conscious process, then I need help understanding the rejection per se of art shaped by dream or intuition, by accident or spontaneity, by drugs or a chance encounter with driftwood on the beach.

Chris, i can't quite fathom what the modern experiment was hoping to achieve by emptying out the image. It seems obvious that it would hit an end point pretty quickly (of maximum emptiness) then swing back to more representational imagery.

ReplyDeleteAnd thus... representational imagery was back in vogue as early as the late '50s - early '60s with pop art (to add insult to injury, Clement Greenberg had only just destroyed 'kitsch'). I know pop art is based around found imagery, collage, and mechanical reproduction, but still, it suggests to me that the 'modernist experiment' was far too limited in scope, and straightjacketed by theories and concepts.

Most importantly (as i tried to illustrate in my previous comment) i think it's incredibly naive to think that a visual art-form could be made that bared no relation to the external visual world (usually the first thing we do when we look at something new is to play the game of 'this reminds me of...').

David wrote,‘“I suppose my point is that symmetry is fine for an initial, rebuttable presumption about the human form, and we might even stop right there if we're drawing idealized people for a Flash Gordon comic strip, but if our goal is to pay attention and depict people as they truly are, that initial presumption is often rebutted by accurate observation.”

ReplyDeleteSorry David I have to go back to the symmetry observation. Artists comprehend large unifying principals that harmonize the many different things that make up the world.. Where a non artist easily sees the differences and inconsistencies between things, they fail to grasp the organizing principal that allows them to remark on the differences. For example someone comments on the difference between the eye on one side of the face and the eye on the other side, but one almost never comments on how the two eyes are related. Symmetry is not ,”rebutted by accurate observation,” it makes accurate observation possible, it allows one to state differences in a definitive way because it reveals how the parts are organized. One needs simple principles and fixed points to ground one’s observations. Even if one wants to draw something that is catawampus.

And I googled Michaelangelo’s Pieta and sure enough your right about the proportions, but the proportions are a result of the need to support the weight of the marble in Christ’s body. Gravity itself forced Michelangelo to increase the Virgin’s size otherwise she would not have been able to support her son. Once something is started artistic decisions often get force by the internal logic of the work itself.

David-“If, as Chris says, 'authoring of art' does not put a heavy emphasis on the conscious process, then I need help understanding the rejection per se of art shaped by dream or intuition, by accident or spontaneity, by drugs or a chance encounter with driftwood on the beach.”

I think that is a good question, if the “subconscious,” is doing the work who observes its actions? And if an unknown force is operating in the artist who is it that decides to take credit for what it has done? Is there even a individual doer(or author) then?

Instead, they want to see conscious "authoring" and "purposeful signification" and "communicative intent." As far as I can tell, this demands a level of control that leaves little room for the subconscious or the happy accident.

ReplyDeleteI think the grand point that you are missing is that the Poet-Artist in each of us is not our consciousness, not the word-centric rule-codifying linear-technical mind, but is, in fact, the subconscious. The subconscious being the oceanic realm of metaphor, association, gestalt, synthesis, resonance, memory, truth, dreams, invention, suggestion, insight, and aesthetic forces that roils within us all.

The whole history of Art instruction, it seems to me, consists of attempts at getting the linear mind to understand the vastly more powerful non-linear mind and its far more profound connection to the world. The intellect is a bad artist, but doesn't know it. And so it must be taught to either understand the imagination, or back off and get out of its way.

The belief that thought is the province of the "intellect" is confused. Thought comes from the much deeper place of imagination enacting sensual force-models of the world and running them. Such cannot be pieced together, or constructed. The models must be synthesized. The parts do not create the whole. It is only the interdependency of forces that create the whole. Parts are a static idea, as are their labels.

The structure of thought, the song-like cascades of inquiry and thematic demonstration that form the argument or the narrative play, weren't invented by the scrivener mind. It was just written down by it after long study and consideration of the results of a great many creative geniuses.

Your brandishing of the word 'control' against what we are saying is distorting. The real matter is realization. It is only the imagination/subconscious that can synthesize an imagined world (a functioning force-model). Thus it is only the imagination that can bring an image into being.

False control comes from the linear consciousness; the mini-mind thinking it can describe a force model into being with static symbols.

Overall, all human products embody the thoughts, unconscious or 'conscious', that led to their making. But not all human products express thoughts.

David and Tom:

ReplyDeleteAs Kev so importantly explained:

I do not make a distinction between conscious and unconscious creative work. Because I don't believe there is a distinction between the motives of the conscious and unconscious. I understand the consciousness as merely the (often mistranslating) messenger and librarian of the unconscious. There's a separation of duties, but not a split in being. I think we are always doing as a whole being. And any illusion of being a fraction of our total selves (a dissociated consciousness apart from the self) is an egoistic delusion caused by the chatty symbol-obsessed part of our minds trying to run the show.

When struggling to build and resolve a work of art my conscious mind is alongside my subconscious mind. The paint, as it goes on, constantly presents me with possibilities (little waywardness's of the brush and 'accidents' of the pigment, the surprise of how a colour is behaving on top of or alongside another or how a different application of it to the one I first thought of and seeing it did not work prompted a different application that did etc etc) - all this is the equivalent of your 'chance encounter with driftwood on the beach.

But there are literally tens of thousands of these 'encounters' (delivered by the inevitable unexpectedness's of brush and paint) as I struggle with the painting. And the feeling of this struggle is the process of a string of decisions and edits about what is 'in tune' with my subconscious sense of the image I most passionately want all of this to resolve into.

In other words, a series of 'finds' selected because of their suitability and orchestrated towards a wordless yet nonetheless very definite and intended meaning.

This is utterly different in kind to the business of coming across something and announcing that it looks expressive. Every brushstroke we make 'looks expressive' of something for goodness sake! :)

ReplyDeleteDavid: "A group of commenters seems to reject the subconscious "Rorschach Test" aspect of what Dubuffet saw in the driftwood on the beach..."

What's the big deal about seeing a face in a piece of driftwood ? As Kev has already noted, go to the woods (or look at the clouds) and knock yourself out.

David: "...and devalue the subliminal response of a viewer to the violence of a Franz Kline brush stroke"

How many rooms of random brushstrokes could you look at before you got seriously bored, and were just begging for a well constructed picture of something ?

David: "They don't seem to allow credit for the subconscious connotations of Barnett Newman's bold vertical stripe in an immense blank field"

Were 'subconscious connotations' the point of that type of art ? see my previous comments.

David: "As far as I can tell, this demands a level of control that leaves little room for the subconscious or the happy accident"

I think the subconscious aspect has been explained above by Kev.

David: "then I need help understanding the rejection per se of art shaped by dream or intuition"

I love a lot of art that evokes a strange, dream-like atmosphere. But it usually has to be well painted or drawn.

David: "by accident or spontaneity, by drugs..."

Depends hugely on the outcome. If you're talking random, vague, abstract expressionist daubing... same answer as to your 'Franz Kline brush stroke' question.