Recently, a column in Editor & Publisher magazine proclaimed that the comic strip For Better or Worse (above) is "the best comic in the 111-year history of the modern newspaper strip." Labeling the creator an "artistic genius," the column argued that For Better or Worse surpasses strips such as Krazy Kat, Little Nemo, Calvin & Hobbes, Peanuts and Terry and the Pirates.

In the LA Times, art dealer Karen de la Carriere asserted that Kinkade, the painter of unmitigated twaddle, "is a modern day Leonardo da Vinci or Monet. There is no one in our generation who can paint like that."

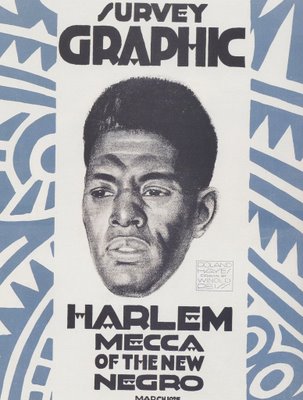

Not to be outdone, the NY Times Magazine pronounced Art Spiegelman the “Michelangelo" of the comic world.

For many years, I thought the only polite response when critics publicly embarrassed themselves was to look the other way, just as you would for someone whose bodily functions got the best of them during a momentary lull at a party.

But when you have a blog like this, you get a lot of traffic from people who insist that everyone is entitled to their own standards, and that taste in art is no different from taste in ice cream. Chocolate, vanilla or strawberry, it's all equally valid. Those people may wish to stop reading now.

There are plenty of reasons for an art critic to be humble. Art means different things to different people. For some it is purely decorative. For others it has religious significance. It can be a form of therapy, a parlour trick, or (in perhaps its highest and best use) a seduction technique. Taste in art changes, so an artist beloved by one generation might fall from grace in the next. Furthermore, wonderful art pops up in unexpected places-- from children, from the mentally ill, from primitive civilizations. In view of all this, who is to say what’s good and bad? If people get genuine pleasure from mediocre art, one has to think twice before telling them they are wrong to do so.

This may explain a recent survey of 230 art critics by Columbia University, which found that passing judgment on art was at the bottom of their list of priorities, while "providing an accurate descriptive account" was at the top. This unwillingness to evaluate quality caused James Elkins, chair of art history at the Art Institute of Chicago, to conclude that art criticism is in a "worldwide crisis" because "contemporary art criticism is entranced by the possibility of avoiding judgment."

In a major essay in the New York Times, Barry Gewen analyzed six art books that survey the state of "fine" art today. Although the books were written from a wide variety of perspectives, they all reached the same grim conclusion: "surveying the trends in modern art leaves one with the sense that we have arrived at the end of something, a state of bewilderment at best, of bankruptcy at worst."

It's a sad ending for a trend that began with such excitement and promise. Nearly 50 years ago, Robert Motherwell wrote:

The emergence of abstract art is a sign that there are still men of feeling in the world .... Nothing as drastic as abstract art could have come into existence save as the consequence of a most profound, relentless, unquenchable need. The need is for felt experience -- intense, immediate direct, subtle, unified, warm, vivid, rhythmic.But Clement Greenberg, one of the earliest supporters of abstract art, added an important qualification:

The nonrepresentational or abstract, if it is to have aesthetic validity, cannot be arbitrary and accidental, but must stem from obedience to some worthy constraint.The absence of a worthy constraint-- of standards-- opened the door to artists such as Bob Flanagan, whose art involved nailing his penis to a wooden plank, or Keith Broadwee whose art involved squirting paint from his anus.

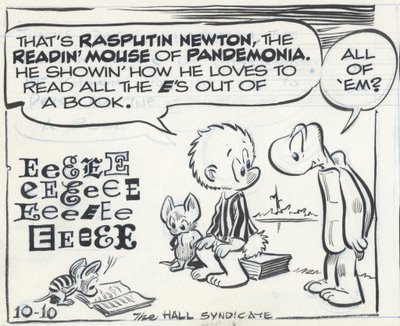

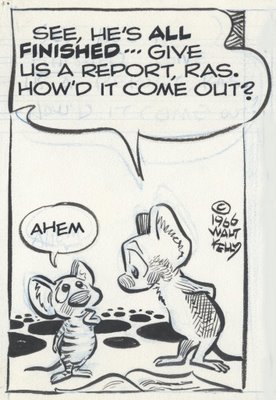

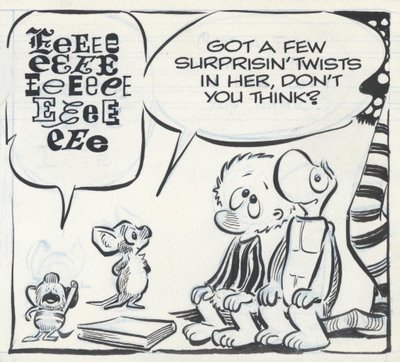

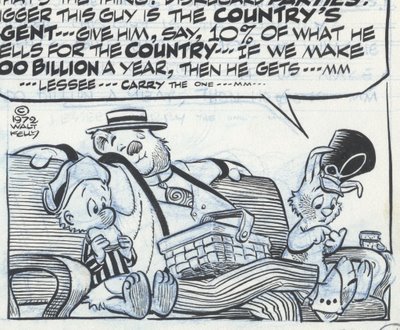

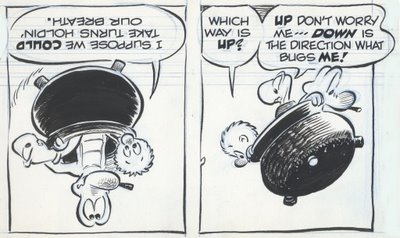

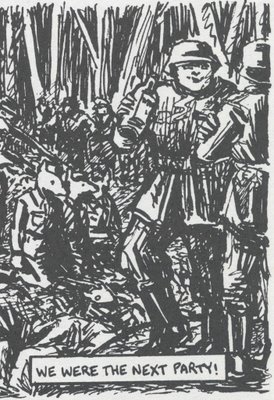

One reason I like illustration and comic art is that it is not as susceptible to narcissism and decadence. As Howard Munce once remarked, "the difference between art and illustration is that there are no amateur illustrators." An honest commercial marketplace may not be the ideal source for purpose and value in art, but it will certainly do until a better one comes along.

In the end, I agree with William Blake:

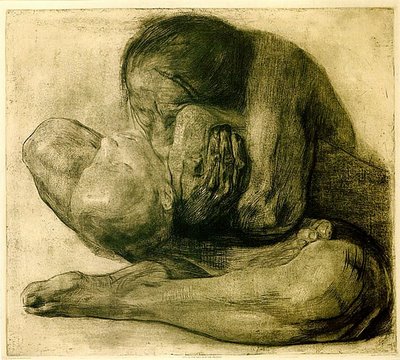

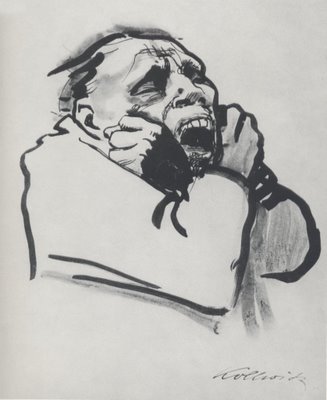

When I tell any truth, it is not for the sake of convincing those who do not know it, but for the sake of defending those who do.Many of the artists discussed on this blog are gifted artists who held themselves to exacting standards. They paid a high price to develop their art in ways other than nailing their penises to a plank. It is to honor their accomplishment that I stand firm on this spot in cyberspace and insist, "standards are not an illusion."

.