Art, being bartender, is never drunk

And magic that believes itself must die

-- Peter Viereck

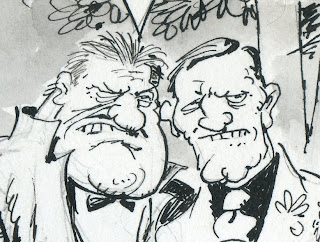

...except it turns out that Peak made several careful studies to achieve that spontaneous look. He re-copied drafts on tracing paper, preserving the elements he liked.

He even drew faint pencil guidelines so he would know the best way to make his bold, slashing strokes appear free and unconstrained:

Peak employed a conjurer's tricks to create the magic in this art. (Viereck described art as "a hoax redeemed by awe.") I'm sure it would've felt personally cathartic for Peak if he reacted to the thrill of the race by making wild, unrehearsed scribbles. However, his drawing looks more vigorous and potent because of Peak's multiple drafts.

David Seymour took the following photograph of a young Polish girl who, after being freed from a Nazi concentration camp, was asked to draw a picture of "home."

There's no questioning the strength of her emotions, but they were so out-of-control that they capsized any effort to communicate with her picture.

Nietzsche wrote that "self-conquest" is necessary to make "torrential passion...become still in beauty."

Shakespeare, who also knew a thing or two about passion, lauded those with the power to move others while remaining in control of their own faces:

When art gets too close to the passions and emotions that inspire it, it tends to melt. In order to move others with art's magic, it seems that at least part of the artist must remain unmoved as stone-- separated from the primacy of experience by proportion, archetype and even skill.[Those] who, moving others, are themselves as stone,

Unmoved, cold, and to temptation slow:

They rightly do inherit heaven's graces

And husband nature's riches from expense,

They are the lords and owners of their faces,

Others but stewards of their excellence.

It is fashionable in some circles to value pictures that appear raw, unschooled and spontaneous (going far beyond the ancient principle that art should appear as effortless as possible in order to prevent technique from becoming a distraction). I like such pictures too, but I think their "spontaneity" is a romantic delusion for the benefit of the conjurer's audience. The artists I like best tend to be the ones who struggle self-consciously to achieve this effect, just as Peak did. The performers who believe their own magic (of which there are many these days) seem consistently less successful.