Not long ago,

Publishers Weekly made the following claim about the art of Jaime Hernandez:

"Jaime's ability to sum up life's joy and pain in a few images has never been surpassed in all of art."

I like the work of Jaime Hernandez as much as the next person but this loony sentence might just be enough to topple the human race from our place on the evolutionary tree.

People have become emboldened to say ignorant things because of our current conceit that art is totally subjective. Personally, I side with Harlan Ellison who wrote, “You are not entitled to your opinion. You are entitled to your informed opinion. No one is entitled to be ignorant.”

When people express silly opinions about art, it provokes the people around them to strain for some kind of rational, objective standard for evaluating art. The problem is, the people who claim to have found scientific standards usually end up in a place equally goofy.

Which brings us to this week's headline: a forensic accountant

claims he has developed a computerized technique for identifying Norman Rockwell's artwork. No longer will you have to judge a Rockwell painting by its artistic merit.

If you research patent #10,460,412 at the Patent and Trademark Office, the inventor claims that in 1940,

Mr. Rockwell created a blend of Posterization and Steganography, the art of hiding data in a cover medium, to provide an anti-forgery feature to his paintings. He created CMYK paint colors that matched the RGB color model and used the colors he created to hide his initials.

Some of you cynics may be amazed by Norman Rockwell's technical computer skills dating back before the invention of the computer. That shows how little you know. In 1938, the first patent application for "posterization" was filed. Apparently, when Rockwell reviewed the daily docket for the Patent and Trademark Office he recognized the potential to adapt these nascent technologies into an anti-forgery system for his own paintings:

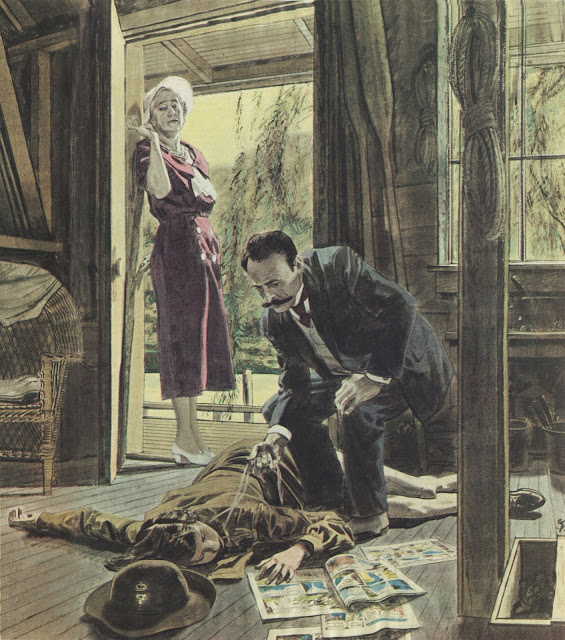

The patent application claims that using this system, Rockwell was able to conceal his own initials in his paintings to prove their authenticity. Here are some of the examples of Rockwell's art in the patent application, processed by computer to reveal his hidden steganographic initials:

Note that in one of these examples, Rockwell supposedly wrote his initials "rn" instead of "nr." No explanation for this is offered.

Based upon this convincing proof, the Patent and Trademark Office granted a patent for this computerized Rockwell detector.

There isn't one character in this process-- including the Patent and Trademark Office-- who wasn't as loony as the claim about Jaime Hernandez.

My point is that we should avoid being coaxed or harassed into either extreme; taste is not totally subjective nor is it objectively provable. Art continues to demand our highest and best judgment, guided by both reason and passion, on a case by case basis.