Ciardiello achieves drama in his drawings by balancing extremes. He contrasts a light, lacy line with dense, powerful black accents. He contrasts black and white drawings with spots of vivid color strategically placed. He contrasts liquid pools of watercolor with a raspy drybrush.

|

| An elegant line contrasted with a thick black brush |

|

| A black and white drawing contrasted with jolts of color (detail) |

|

| Liquid pools contrasted with scratchy drybrush (detail) |

Ciardiello's balance of extremes is delicate surgery in a small space, but when the elements interact well the result is potent images. Over the years he has produced many excellent pictures in his distinctive style.

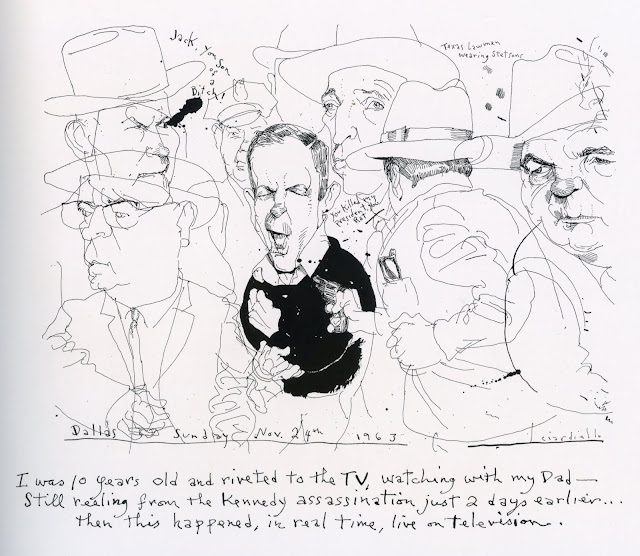

Now Ciardiello deserves credit for a different kind of achievement: rather than wait for paying clients to offer him suitable and meaningful assignments in today's parched illustration market, he set out to create his own book of work he could be proud of. Between other assignments over the past five years he has composed a new book, A Fistful of Drawings. It is a rare opportunity to see a mature illustrator, unfiltered by art directors and clients, creating images answerable only to himself.

The book is a "graphic journal," a personal memoir about his life and the popular culture he admires. His pictures include everyone from the Lone Ranger and Annie Oakley to Bettie Page and Al Capone, but he saves his most loving treatments for the movies and movie makers of his youth. His text is integrated into the pictures as his own handwriting, which is a cross between drawing and lettering.

Here are some of my favorites from the book:

|

| I think this is an extraordinarily beautiful page, a sophisticated and unorthodox design in which opposite extremes create a healthy tension. |

|

| Some of Ciardiello's pen and ink caricatures are reminiscent of David Levine but unlike Levine Ciardiello uses strong black elements to transform his compositions. |

|

| Ciardiello's mix of sensitive descriptive line and abstract design |

I think the following double page spread is a real stunner, one of those pieces where the line between illustration and fine art seems to disappear.

The following detail shows how abstract color splatters help loosen and expand the scope of a representational drawing.

Ciardiello's book is for sale from Fantagraphics.