I admit it's difficult to criticize work such as Maus or Fun Home merely because the authors don't draw well. Still, an artist who chooses to work in a visual medium can't simply ignore the qualities of that medium.

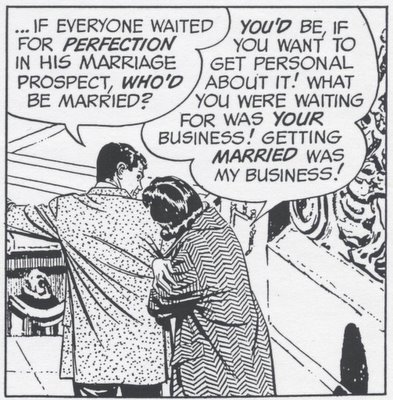

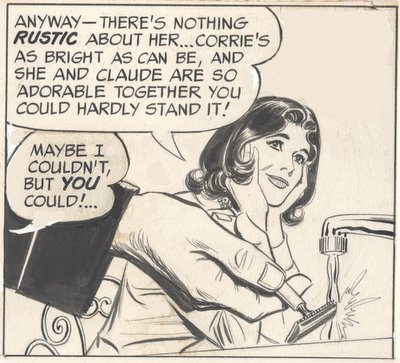

More importantly, I don't think the epithet "commercial" is a reliable tool for separating good art from bad. There are many awful pictures of heartfelt subjects, while there are many brilliant pictures of dish washing detergent or automobiles. As far as I can tell, nobody has yet established a connection between purity of motive and quality of art. (As Oscar Wilde noted, "A thing is not necessarily true because a man dies for it.")

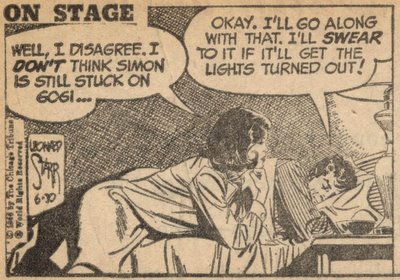

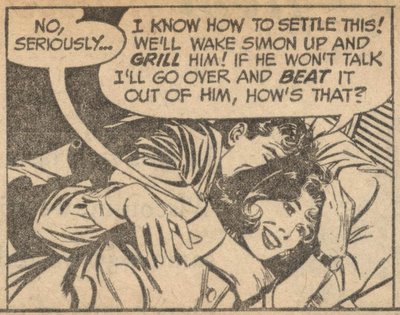

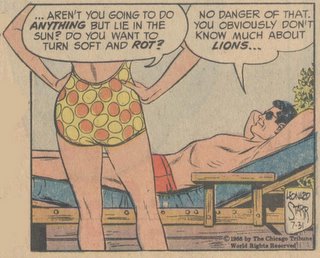

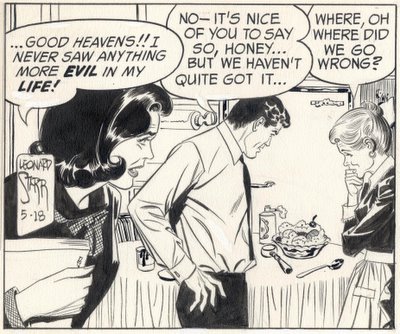

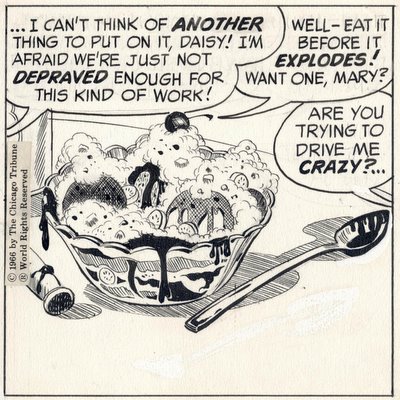

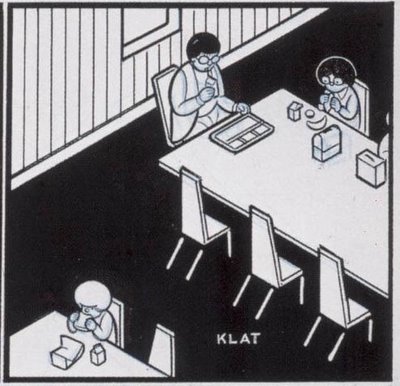

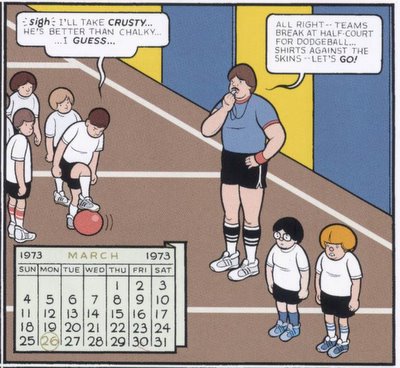

| ||

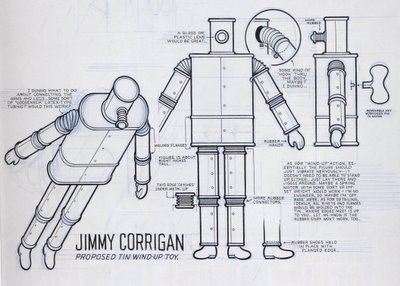

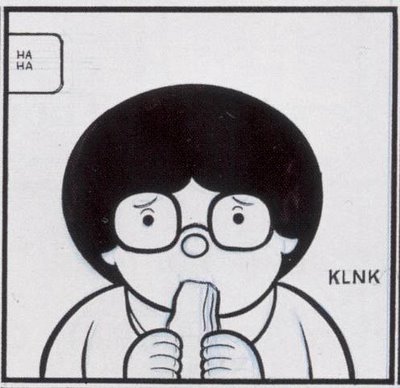

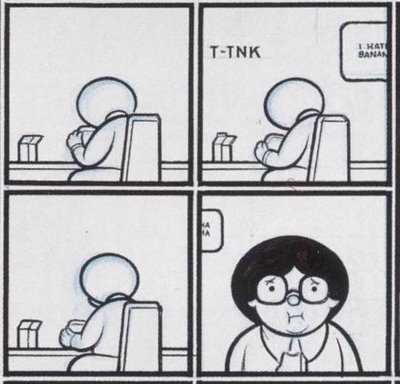

| It is possible that "most men lead lives of quiet desperation," but after trudging through Chris Ware's endless stories of slow misery, we might wish desperate men would be a little quieter. |

If pure motives and authentic emotions are what you seek in art, I'm not sure you'll find much difference between commercial illustration, graphic novels and pictures hanging in the Museum of Modern Art. They can all be equally commercial. (Andy Warhol famously remarked that "good business is the best art.") So before you accept mediocre drawing and bad compositions as the trade off for authenticity, check out some of the following"outsider" artists. They are every bit as tormented as Alison Bechdel or Chester Brown, yet they still manage to meld their feelings with beautiful compositions and quality images.

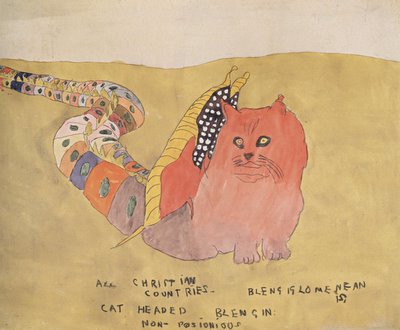

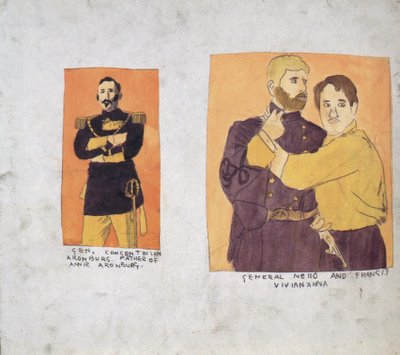

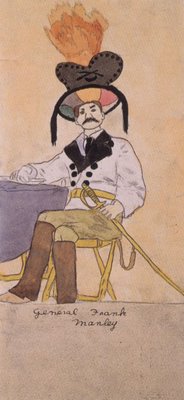

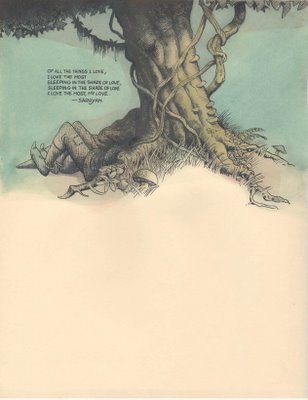

For example, the artist Henry Darger was an impoverished janitor who lived for 50 years in a shabby apartment so tiny he had to sleep sitting up. He worked far into the night illustrating his magnificent graphic novel, In the Realms of the Unreal.

Darger led a life of isolation and pain that makes Jimmy Corrigan's life look like a day at Disneyworld. Yet, Darger's artwork is filled with dazzling images. He did not use his suffering as a justification for ignoring the challenges of composition, design, color or the other ingredients of his chosen medium. His beautiful pictures were able to advance, rather than work in opposition to, his troubling personal message.

It is also worth noting that Darger's text never dwelled on his own suffering and insecurities. Instead, he elevated his personal misery to tragedy through his art. You will find no self-obssessed whimpering in Darger's work.

He kept these illustrations to himself until the day he died. He was not working to impress the critics or collect royalties. He used art in a genuine struggle with his own personal demons.

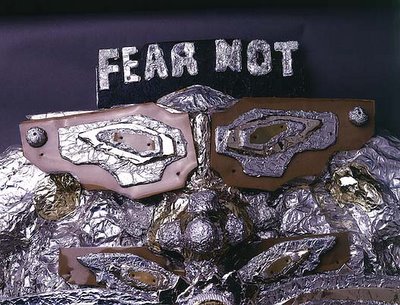

Another "outsider" artist I admire, James Hampton, lived a lonely life obsessing about religious salvation. Beginning in the late 1940s, Hampton began writing about his religious visions using pictograms and secret codes.

He drew marvelous symbols such as lightning bolts and omniscient eyes. Hampton spent the last fifteen years of his life integrating these symbols and pictograms into astonishing sculptures comprised of aluminum foil, light bulbs and pieces of old furniture.

He called his strange and beautiful masterpiece, "The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly."

James Hampton

Like Darger, Hampton was not trying to get a deal with a Manhattan gallery or to impress Art News. He was not trying to tell the world about the unfairness of his life as a janitor. Hampton's own landlord had no idea what Hampton was up to. After Hampton died, his landlord was shocked to discover Hampton's masterpiece in the unheated garage where Hampton had labored all those years.

The Throne of the Third Heaven is made up of 177 separate art objects, combining words, symbols, drawings and sculpture. Standing before it, the cumulative effect is enough to inspire dread for your immortal soul.

Although they never received the celebrity status of a Spiegelman or Ware, I think Darger and Hampton's work is far superior. Darger and Hampton worked with greater handicaps, under more difficult circumstances, and yet made better art.

And there are plenty of other artists out there like Darger and Hampton. Often untrained, working in obscurity and poverty, ignored by the New York glitterati, "outsider" artists work only to serve their god or their muse, or sometimes their alien leaders on the planet Zarbtron.

There is also an important philosophical distinction to be drawn here, which should probably be irrelevant to a blog about illustration, but which I confess colors my judgment of this art.

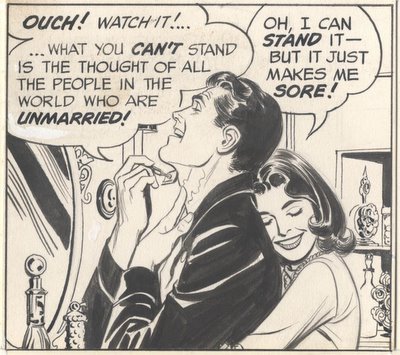

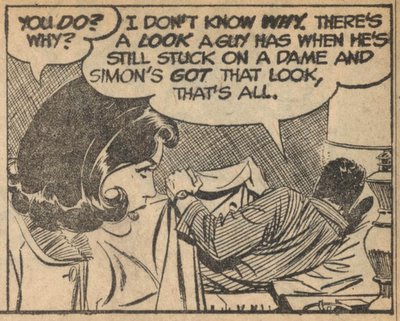

It seems to me that these outsider artists responded to their personal pain and to the weight of their humanity in a more noble, less self-indulgent way than the graphic novelists who are winning Pulitzer prizes and big royalties for sharing their pain with us.

The guys who seem to understand the most about this tragedy business-- Shakespeare, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripedes-- remind us that suffering and doom are an inescapable part of the human condition, but seemed to believe that we retain one meager defense: the tragic hero's capacity to elevate mere misery into the majesty of tragedy. This is done through courage, perseverance and understanding in the face of hopelessness. (Not much of a consolation prize, I admit, but hey, what other options are you offering?) My purely subjective judgment is that Jimmy Corrigan dwells at the misery level. I find no nutritional content that would reward a second or third reading.

There are thousands of "outsider" artists, some making beautiful art, many making terrible art. But if you are the type who rejects "commercialism" in art and strives for artistic purity, put down your graphic novel and invest a little time with real outsiders. If the fragrance of commercialism offends you, you must be prepared to hang around artists who don't use soap regularly.

He kept these illustrations to himself until the day he died. He was not working to impress the critics or collect royalties. He used art in a genuine struggle with his own personal demons.

Another "outsider" artist I admire, James Hampton, lived a lonely life obsessing about religious salvation. Beginning in the late 1940s, Hampton began writing about his religious visions using pictograms and secret codes.

He drew marvelous symbols such as lightning bolts and omniscient eyes. Hampton spent the last fifteen years of his life integrating these symbols and pictograms into astonishing sculptures comprised of aluminum foil, light bulbs and pieces of old furniture.

He called his strange and beautiful masterpiece, "The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly."

James Hampton

Like Darger, Hampton was not trying to get a deal with a Manhattan gallery or to impress Art News. He was not trying to tell the world about the unfairness of his life as a janitor. Hampton's own landlord had no idea what Hampton was up to. After Hampton died, his landlord was shocked to discover Hampton's masterpiece in the unheated garage where Hampton had labored all those years.

The Throne of the Third Heaven is made up of 177 separate art objects, combining words, symbols, drawings and sculpture. Standing before it, the cumulative effect is enough to inspire dread for your immortal soul.

Although they never received the celebrity status of a Spiegelman or Ware, I think Darger and Hampton's work is far superior. Darger and Hampton worked with greater handicaps, under more difficult circumstances, and yet made better art.

And there are plenty of other artists out there like Darger and Hampton. Often untrained, working in obscurity and poverty, ignored by the New York glitterati, "outsider" artists work only to serve their god or their muse, or sometimes their alien leaders on the planet Zarbtron.

There is also an important philosophical distinction to be drawn here, which should probably be irrelevant to a blog about illustration, but which I confess colors my judgment of this art.

It seems to me that these outsider artists responded to their personal pain and to the weight of their humanity in a more noble, less self-indulgent way than the graphic novelists who are winning Pulitzer prizes and big royalties for sharing their pain with us.

The guys who seem to understand the most about this tragedy business-- Shakespeare, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripedes-- remind us that suffering and doom are an inescapable part of the human condition, but seemed to believe that we retain one meager defense: the tragic hero's capacity to elevate mere misery into the majesty of tragedy. This is done through courage, perseverance and understanding in the face of hopelessness. (Not much of a consolation prize, I admit, but hey, what other options are you offering?) My purely subjective judgment is that Jimmy Corrigan dwells at the misery level. I find no nutritional content that would reward a second or third reading.

There are thousands of "outsider" artists, some making beautiful art, many making terrible art. But if you are the type who rejects "commercialism" in art and strives for artistic purity, put down your graphic novel and invest a little time with real outsiders. If the fragrance of commercialism offends you, you must be prepared to hang around artists who don't use soap regularly.