Illustrator Chris Payne sometimes roughs up his drawing surface with a brayer. He combines ultra matte medium and thinned acrylics, rolling out a textured foundation for his pencil drawings.

Friday, November 29, 2024

BACKING AWAY FROM THE FASTIDIOUS

Tuesday, November 12, 2024

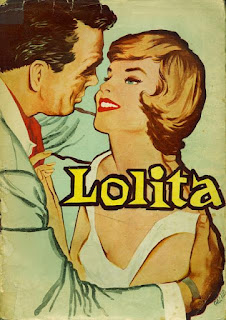

LOLITA'S LITMUS TEST

It's hard to think of a more challenging test for realistic illustration than Vladimir Nabokov's book, Lolita. Nabokov emphasized to his publisher that any illustrator who attempted a representational image of the character would be missing the point. He wrote: "There is one subject which I am emphatically opposed to: any kind of representation of a little girl."

The difficulty of illustrating Lolita has been widely recognized. The (excellent) book, Lolita; The Story of a Cover Girl contains essays and dozens of images on "Vladimir Nabokov's novel in art and design." Lit Hub compiled a (useless) survey, The 60 Best and Worst International Covers of Lolita and here are 210 covers over the years. In 2016 The Folio Society produced what they called the First-Ever Illustrated Version of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita."

Many artists and art editors have tried coming up with realistic illustrations for Nabokov's psychologically complex novel but the results have been pretty worthless:

|

| Illustration for the recent Folio edition |

Wednesday, November 06, 2024

DID SOMEBODY STEP ON A BUTTERFLY 62 MILLION YEARS AGO?

I'm taking a 24 hour break from our series on digital art to observe election day in the United States.

Here are a few panels from a classic Al Williamson story for EC, written by the prophet Ray Bradbury.