**This cross-posted collaboration features an attitudinal stimulus package by David Apatoff of Illustration Art with peacay of BibliOdyssey on image wrangling and cattle prod detail.**

Hubert François (Burguignon) Gravelot 1669-1773 trained in Paris as an illustrator-engraver under François Boucher and came to London in about 1732. He was friends with William Hogarth and they both taught at the St Martin's Lane Academy, something of a precursor to the Royal Academy. Thomas Gainsborough was known to have studied under Gravelot.

From France, Gravelot brought with him the ornate styling of the rococo, which he helped promote in his thirteen year sojourn in England. He contributed designs for goldsmiths, furniture makers and the commercial print trade, but his book illustrations - for luxury editions - were particularly influential. He illustrated Gay's 'Fables,' Shakespeare and Dryden, and was one of the first artists to illustrate the novel, designing engravings for Richardson's 'Pamela' and Fielding's 'Tom Jones.'

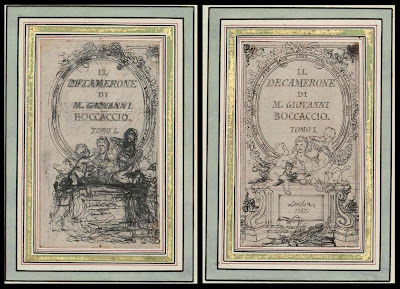

Of the ten images below, the first eight were preparatory sketches for the 'Decameron,' the second-to-last from a Voltaire compilation and the final image is from an unnamed collection (links at the end of the post).

I've been told that one way to measure the quality of an oriental rug is to count its borders. Generally, the more borders around the rug, the more complex it is, and the higher its quality. But I usually find the opposite to be true of drawings: the more fancy borders required to make a drawing look important, the weaker the drawing tends to be. The owners of these Gravelot pictures have surrounded them with up to 14 borders and embellishments (some of them in gold) before you finally hone in on his drawing. Even then, we're not done. Gravelot encircles some of his own drawings with yet another ornate border-- a decorative wreath bedecked with the tools of the arts and sciences, or the symbols of the theatre, or fawning muses overwhelmed by the brilliance of what the reader is about to behold. By the time you finally get through to the drawing itself-- the image at the core where the artist demonstrates what his hand and eye and imagination are capable of-- the viewer has some pretty high expectations.

Unfortunately, I don't see a whole lot here to suggest that Gravelot's drawings satisfy those expectations. These are light, capable drawings. I can understand people preserving and studying them for their significance to the history of the engraving arts, or the manners and customs of his day, but not particularly for the quality of the drawing. Unfortunately, the quality of the drawing is usually the part that interests me the most.

When Gravelot was drawing these pictures, his artistic choices were limited by the fact that the drawings would have to pass through a cumbersome engraving process that was already more than 300 years old. First, the drawing would have to be transposed onto a wood block or metal plate. Next, the plate or block was turned over to an engraver who attempted to carve the image into the surface using sharp and unwieldy tools. This process effectively prevented an artist from drawing in certain styles; Gravelot could not get too spontaneous or fluid with his line, or use half tones in his picture. Finally, the printed picture ended up as a mirror image of the artist's original drawing. The result of this arduous process was a picture several stages removed from the artist's concept.

Not long after Gravelot died, photoengraving replaced engraving as the technique for reproducing art in books and magazines. The new technology set artists free and transformed the entire field of illustration. Delicate nuances in line, subtle gradations in color, detailed images were all reproduced with much greater fidelity, permitting artists to do their very best.

Gravelot may have played an historically significant role as a designer and engraver, but his drawing seems pretty anemic to me. You can see from these preliminary studies how often he has to go back to re-work simple figures he should have been able to visualize and lay out straightforwardly. [title page, outside crowd scene]. Note how tentative his line work is, and how heavily dependent he is upon mechanical tools such as the grid for his vanishing points. [kitchen scene, Imprimerie] Most capable artists could simply intuit perspective in drawings this small, with subjects this simple, but Gravelot's preliminary drawings seem to reveal a well deserved lack of confidence.

One of the purposes of an illustration is to help stretch the reader's imagination by providing an artist's vision of the story. It is ironic then, that illustrating a book as bawdy and rich as the Decameron, we are presented with such wan and lifeless drawings. It's hard to imagine that a reader could not do better on his or her own imagination. These illustrations seem to serve as a visual chastity belt, keeping our minds within legitimate boundaries rather than titillating and unleashing them. There is no commitment or emphasis here, no urgency or merriment in the art to correspond to these stories. By today's standards for illustration, this work seems like a real mismatch between form and content.

- 'Drawings for the illustrations of Boccaccio's Decamerone' {Rosenwald 1645} [book published in 1757].

- 'Théatre de Voltaire; dessins par Gravelot' {Rosenwald 1604} [book published in 1768]

- 'Original Drawings' {Rosenwald 1657} [undated]

- Biographical material: one; two; three.

- Art works: one; two; three; four; five.

9 comments:

I just visited Bibliodyssey. That's a great site!

I am on this blog as an rss, and I receive email updates at least three times a day that this site has been updated. I look, and it seems just the same. Do you know why this is happening?

David, don't assume that mainstream art/illustration (if can be called like that at the time) was of similar quality as the great masters of paint of its time. That's why almost no one remembers Gravelot.

He seemed to have had enough respect to make a decent living and a name in its time, and probably the style was fashionable... think how many capable -yet uninspired- illustrators make a good living on our time? Probably they will be forgotten in a few years, but they are accepted and praised now.

Paraphrasing Oscar Wilde, fashion is something so horrible that we should change it constantly!

Gravelot's lack of energy cannot be laid to the reproduction process. Winslow Homer drew illustrations for the very same reproduction process and his commercial work managed to survive with some degree of energy.

Engraving does not impose lacklustre concepts and compositions on the artist, witness the superb illustrations by Winslow Homer in Harper's Weekly and Balliou's or the lively copper engravings of Albrecht Durer. Those are distinguished artists with original concepts. Alas, the same cannot be said for Gravelot.

As I was told as a young illustrator..."it's a poor workman who blames his tools." You learn the limitations of the medium and work withing them. Homer and Durer pushed the edges of their mediums. Gravelot simply did not have the energy or wit to do likewise.

Thank god for Howard Pyle!

But seriously this stuff is weak tea. There's almost nothing to say about the actual work except that it makes Quakers seem like lunatics. It out-solemns monks. It is so utterly constrained by sullen, somnabulent prosaicism, it frankly makes me edgy when I look at it. Away with it!

Reminds me, I once heard Neal Adams give a hopeful but uninspired artist a critique at a comic convention. Adams angrily asked the artist, trying to awaken some passion in him, "Are you falling asleep at the drawing board!" I'm afraid Mr. Adams might have caused Mr. Gravelot "a nervous episode" had it been possible that they could have met.

I've always thought that reproduction changes an artform. Think about music before records and victrolas. To hear a great orchestra play was a great and rare event for most, even if the actual music played wasn't quite one of the classics. If you've ever listened to classical music randomly, it becomes quite evident that boatloads of it was simply atrociously boring and uninspired. Like aural wallpaper.

But, go figure, as soon as records come about, we get jazz and tin pan alley and avante garde and hybrids like Rhapsody in Blue and Ellington. The novelty of just experiencing sound wears off and soon only top quality, pushing the envelope, total novelty, or something fun is worth nodding at.

Gravelot could function in the days before quality reproduction and color and photography because all that was needed was a drawing and how delightful that must have been! Wallpaper had just been invented. Reminds me of that "dog that can dance" joke... it isn't that it is done well, but that it is done at all.

I'm also one of those people who has zero interest in the historicity of artworks. If some old master does boring work, I don't care if he's an old master or not, it's still boring and not worth wasting a moment on. Historicity in art is just history. It has nothing to do with artistry.

Anyway, great post,

kev

I agree with most of the crits, but I disagree that orienting simple scenes to a vanishing point is a sign of timidity. It's just smart drawing. Even simple scenes contain strange angles that may elude the artist. Regardless of one's experience, it's more quick and sure to map a simple grid than to guess at the lines.

Second anonymous, I can tell you that peacay and I had a couple of false starts the morning that we launched this post because we had some technical difficulties in coordination. I posted and took it down about 3 times. Other than that, I can't account for why you would receive email updates 3 times a day on other days if you have only one rss feed. (I do sometimes go back into old posts if I can replace a mediocre quality image with a scan from an original, or if I notice I've said something particularly stupidly, but that doesn't happen three times a day). I have a list of civic improvements I need to make to this blog, and I will add your concern to the list.

dfernetti, I don't disagree (although I note that hundreds of years later Gravelot's "art" is enshrined in the Library of Congress and various art museums). Most of today's "uninspired illustrators" won't be able to rely on such kind treatment from posterity.

Rob and Kev, I agree with you both about the quality of Gravelot's work. It is interesting that at peacay's blog, Bibliodyssey, they tend to think I was too harsh on ol' Gravelot. That blog is visited more by scholars, historians, archivists, and people who are more interested in understanding and categorizing the humanities. I think this blog is visited more by practicing artists and illustrators (who are, as we all know, heartless judgmental bastards).

Jesse, I can certainly understand a few light lines to make sure you stay on track. But it seemed to me that even in some of the drawings without complex angles or difficult challenges, Gravelot laid down a pretty heavy handed grid, in lines as solid as the lines he used to emphasize his key characters. I guess I think that in situations like that, many 20th century illustrators whose work is not in museums would have been able to "get it right" without quite so obvious a reliance on the grid.

Post a Comment