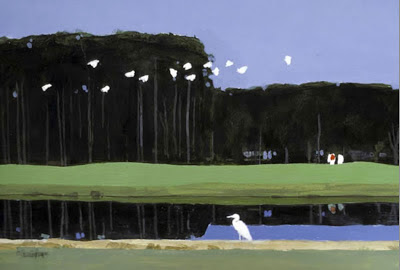

Look at the restraint in this terrific painting by illustrator Robert Cunningham. How does he persuade us that his simple blobs of white paint are birds taking off, while the very similar blobs of blue paint right next to them are openings in the trees?

|

| No eyes, beaks, feathers, feet-- barely even wings-- yet these are lovely birds. |

A lot of wisdom and an awful lot of drawing goes into Cunningham's ability to capture the essence of birds in such basic shapes

Cunningham was born in Herington, Kansas, where the flat plains stretch almost forever. He grew up leading a simple life as the son of a railroad man. Later, art critic William Zimmer observed, "His native ground has perhaps been an inspiration for the flat, bright planes of color that characterize his work."

Whatever the source of his inspiration, Cunningham never learned to hide behind a lot of frills.

|

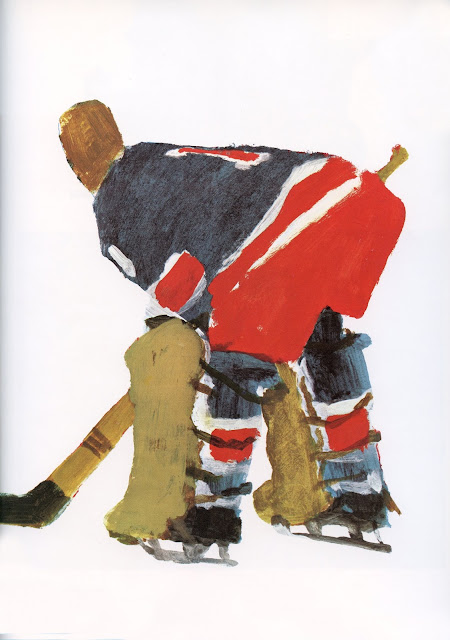

| Marvelous! |

Cunningham got his first big break in illustration when the visionary art director Richard Gangel spotted his talent and put an 8 page portfolio of Cunningham's work in Sports Illustrated. From that day on, he developed a long list of discerning clients. He was elected to the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1998.

|

| Small touches such as the sunlight through those fins show us that Cunningham knows exactly what he is doing. |

It's hard to resist showing off our abilities-- our talent for drawing precisely, our eye for detail, our skill at making fine lines-- but restraint implies a power greater than all of these: the strength to harness our other strengths. It shows that we are truly the master of our skills.

114 comments:

Although what we see here is representational, Cunningham seemed to focus on reducing his works down to almost pure composition.

Right he's decidedly graphic design-y before illustration and cartooning decided took a left swing into the field in general.

I find that getting things to fit right in the way they do in these compositions can be just as addictive as 'skill oriented' drawing. However, it can much more frustrating. Nice post, I'm glad to know about this guy.

Thank you for highlighting this man's work.

I feel like the photographic references are a bit too obvious in Cunningham's work, he doesn't seem to have the chops to move away from them, and it seems more likely that the pleasant simplification in his work is a happy mistaking, owing to the fact he is making them specifically to be turned into serigraphs.

In his works where the figures are complex, his ability to show them with any elegance collapses.

It's not quite as clear in those you've shown, but in a number of his other works, the "mono-lens" effect of the camera becomes glaring, his work, I believe, is more obvious to detect for what it really is -- lifeless and unskilled copies of photographs.

I do not mean to disparage working with photographic reference. There are a number of posts on your own blog that show how a photographic reference in the hands of a skilled artist will take on a much larger life. I just don't see this as being one of those cases.

In the end this work seems not unlike the work my classmates in highschool were making using the photograph-to-grid transfer method.

example 1

example 2 (sorry about the size)

In spiritual terms, we call that "humility" or "meekness." Not the lack of power but power restrained.

Here are a handful of other artist's serigraphs to make that point a little more clear--

one

two

three

Bob is remembered at the Society as a true artist and gallery painter. You'll never meet a more humble honest artist. Richard's serigraphs use flat colors but have no artistic relation to what Cunningham does. Bob is more like Diebenkorn.

Perhaps some commenting here know so much about art and method they've lost the naive ability to see and appreciate the picture.

Scott:

Richard's criticism of Cunningham is absolutely valid. He is simply articulating a reservation many would feel about such work, but do not have the knowledge to put their finger on why.

As to your point in general, I believe the appreciative paradigm you are in favour of requires 'innocence' and not the 'naivety' you suggest.

Donald Pittenger-- I agree that composition is huge for Cunningham and, being similarly inclined, that is enough to make me partial to his work. However, I think he brings at other important qualities to the table as well. First, I think he is not just representational, but representational in a real smart way. Those birds aren't prototypical birds in standard bird poses. Cunningham represents them with the insight of a zen ink brush master. Or When you look at his representation of the surf in my last post about boats, he understands where the blue water would turn green at the crest of the wave as light passes trough it, but it is represented with the deckled edge of torn paper and white spatter. Also, when you decoct subject matter down to the level of simplicity that Cunningham does, you quickly reach that Barnett Newman level, where the placement of a single stripe becomes imbued with great importance because that's all there is. (For Barnett Newman haters, that means there is nothing, but for Barnett Newman lovers that means there is everything).

Conor Hughes and plaisanter-- Thanks, I'm glad you like him. I included one image by Cunningham in a recent post about boats on water and heard from a number of Cunningham fans who said that Cunningham was always one of those solid gold illustrators who has been neglected because his simplified form and content don't resonate with an audience demanding more and more pyrotechnics. I think there is a lot there to appreciate.

Richard-- This seems to be the modern battle ground for many bright and articulate people: "I feel like the photographic references are a bit too obvious in _______'s work."

Most (but not all) people made their peace with some form of photo reference after they discovered that Cezanne, Degas and Lautrec relied on photographs. But after that, the consensus ends, especially because the technology continues to evolve and "how much is OK?" becomes a new question with each passing decade. Merely drawing from photographs turned into projecting them on a surface which turned into light boxing them which changed to scanning them which changed to applying increasingly subtle filters to turn them automatically into your own pastel picture or watercolor or mezzotint. If you're doing a caricature, you use the "liquefy" tool on a face. If you are looking for a composition you use the "divine proportion" tool.

This identity crisis for art shows no signs of ending, as computers perform more and more of the functions once performed by human skill (and perform them faster and cheaper). Why should photography and its technological allies back off? They've had nothing but victories so far. It remains to be seen whether artists are following in the footsteps of John Henry.

In this context, I think it becomes incumbent on every knowledgeable observer to make his or her own peace with that point along the spectrum where "photographic references become a bit too obvious" (recognizing that this point may change as technology makes it easier for artists-- or Photoshop technicians-- to cover their tracks and become less "obvious.")

I start with this background because I think a number of people who set out to draw the line on how much photo reference is too much-- including many with a sophisticated understanding of how the technologies work-- focus on the forensics and overlook some of the gentler aspects of human involvement. To those people I would say, "don't draw any bright lines you may later regret" because we are living in times of great change, and your principled stand may soon be overrun by Adobe.

The annals of this blog are overflowing with smart, incisive comments from readers far more intelligent and experienced than I on this subject. In my dotage, sitting in a rocking chair on a porch somewhere with drool coming out of the corners of my mouth, I may try to go back and attempt to bundle some of that wisdom together. But in the meantime, my own instincts are that the "too much photo reference" factions sometimes throw the baby out with the bath water, and I have tried to point out what I think is important evidence of the human stain in pictures where I think it will be an important element in the re-defintion of art. (Most recently, at http://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2013/03/warring-with-trolls-part-2.html I offered my views on an obviously photo-referenced drawing by Robert Fawcett).

In that same vein, I place value on elements of Cunningham's pictures which you apparently do not. I think it's a very worthwhile use of this blog for me to try to explain what I see and to get your reaction to them if you are willing. However, I'll have to start that in a separate comment because I am about out of space on this one.

Chris Bennet,

I'll let Apatoff deal with Richard's comments as he's now doing. As for you, I chose the word "naive" in this instance with care and calculated against certain criticisms of the pictures, and I surely did not suggest a childlike innocence.

Most sincerely,

ScottLoar

Cunningham has a real talent for simplifying the colors and values and shapes of a scene, while keeping the tone and color quality of the day and how it effects the environment. That's no mean ability. This, plus his deft mark-making results in really fresh-looking designs. Quite pleasing and pretty. His stuff would look fine on the walls of an hotel.

However, there isn't the slightest bit of subtext to anything he does. So in that sense his work really isn't composed so much as designed. And without subtext haunting his depictions, his work really feels dead and shallow. At least to me.

And even though he is quite a bit more human in his brushwork, there is something about his stuff that recalls a photoshop filter. After all, the reason such filters exist in that program is because of guys like Cunningham and all the other tracer-designers of his quick and fashionable era.

During the heyday of art, before hip was invented, it was said that the brain was a sixth sensory organ. And its ability was to detect ideas. Which, one eventually learned, never appeared on the surfaces of things. The quality of a sense of mind is the most unique human element. And this is just why there is no making peace with photos as the foundation of an artwork. They are lifeless gatherings of light rays bouncing off the surfaces of objects that have been frozen in the capturing. It takes a heck of lot of lightning to re-animate that corpse.

"ScottLoar said... Perhaps some commenting here know so much about art and method they've lost the naive ability to see and appreciate the picture."

I don't want to sound a braggadocios, but I think you're absolutely right.

When learning image-making techniques a number of images you might've liked before begin to lose some magic as it becomes obvious what went in to making them.

And you're right, that's not necessarily a good thing.

Perhaps, one is caught between two extremes?

On the one hand, we don't want to become mere technicians. Blind to the image, because we too clearly see what went into making it. We don't want to end up like the work of too many math-rock and experimental jazz musicians -- technically impressive, but stone dead. Avoiding that is something I think about regularly.

Opposite that is the visual illiterate, so to speak, one who doesn't appreciate any of the subtleties of the image making process. One who "just likes" pictures, but doesn't have any idea why. Obviously not something one should aspire to be either.

It's fun to think about.

David, I think that Fawcett drawing is killer. Yes, he worked fairly directly from photo refs but he took them somewhere.

I think part of it was that Fawcett was converting them into line work, which required more 'lightning', to borrow Kev's terminology, but there are artists working at roughly the same time as Cunningham who took fairly flat photo-ref'd paintings and made something wildly exciting with them. Euan Uglow comes to mind.

Richard, ScottLoar, chris bennett, kev ferrara-- Richard writes, "It's fun to think about," and I agree whole heartedly. This is going to be more fun than I can realistically squeeze into the breaks between conference calls at my office, so I'm afraid I will be responding in bits and pieces rather than with some unified field theory that this subject deserves, at least until I get home tonight. But let me offer a few thoughts to help frame the larger landscape.

I think Kev underestimates the extent to which we live in a time of disintegration. You can dismiss the path of "fine" art over the past century (we have crossed swords on that before) and dismiss the impact of photography ("there is no making peace with photos as the foundation of an artwork") and before long you might end up in one of those atelier monasteries where Luddite purists proudly grind their own pigments and claim that all of these modern developments are tools of the devil. (I'm not saying you're there, I'm just saying that could easily be the logical extension of some of these positions.)

But as the saying goes, "reality is that which, when you don't believe in it, doesn't go away." If you can't make peace with Cunningham's use of photos, how do you feel about the way Steichen combined photos with his own manual coloring and manipulation? How do you feel about the way Matt Mahurin manipulates photographs to make illustrations such as that devastating picture of the man tethered to the bomb, gnawing his hand off. (Sorry, I don't have the means to attach a jpg right now.) I think it becomes difficult (and after a while, pointless) to deny that these are objects of aesthetic value, even if we have trouble categorizing them on the food chain. And don't rule out the possibility that this fast evolving art form could become the dominant force on the food chain, gobbling up the art forms that you now consider "true" and "good." Some day "photo-reference" may not have the stigma I detect in some of the comments from you nostalgia fans out there. Some day, it could become a virtue. (Your most cherished paintings could one day share the fate of those black and white movies that can no longer command the attention or respect of kids weaned on 3D color.)

What do we lose if that day comes? Well, certainly our romantic notion of the heroic artist gives way when a school girl randomly snapping photos on her cell phone might come up with a stunning composition, or even an image which (unintentionally) has a poignant and profound subtext, which Kev finds lacking in Cunningham's work. But it is not our job, I think to defend the notion of the heroic artist (especially when the task of defending it requires us to go down the very unsavory path of investigating the pedigree of each image: "how did they achieve that result? how much of the skill was their own? who influenced them?") That's a difficult standard to police. Even the standard that I once thought would be the permanent bright line-- plagiarism-- is more difficult to police these days.

But to see how far the situation has already devolved, look at the extent to which very popular illustrators today draw like crap. Some of them must be thinking, "what's the point in developing the discipline? I don't want to compete with the camera, so I need to retreat to my own conceptual turf, where the camera can't go. And to make sure no one judges me against a camera, I'll draw puerile little squiggles to embody my great ideas." Another few decades of that and people will have very legitimate questions about the value of what you are defending. They may abandon the barricades in droves.

On the other side, there are those who will say, it's the picture that matters, not its pedigree or the process by which it was created. But this is problematic too.

(cont.)

(cont. from above)

Personally, I have not pitched my tent on either end of the spectrum. Neither, I think, has Cunningham. (I've got to get back to him). As a sneak preview of my views, I think Cunningham has an excellent eye and sense of design, that his pictures are deceptively simple and that we can't cheat him out of accomplishments such as that hockey player with comments like "photo-reference." In fact, I'd say the true achievement of that hockey player has nothing at all to do with photo-reference. Similarly, I don't disqualify Cunningham for lack of "subtext" because I think you can find subtext almost everywhere, even in Barnett Newman's abstractions (or to pick a less inflammatory example, Degas' portrait of a horse.)

For example, Kev, I'd say that in palette and tone, Cunningham's island pictures resemble some of Winslow Homer's Bermuda watercolors, but distilled to the nth degree. How would you describe the subtext of Homer's pictures, and how would they compare with Cunningham's?

More later.

"But to see how far the situation has already devolved, look at the extent to which very popular illustrators today draw like crap."

Perhaps that work is very popular because people like it so much.

If you're talking about the sort of intentionally naive contemporary illustration I suspect you are... well, I live and breath for that stuff.

Richard wrote, "If you're talking about the sort of intentionally naive contemporary illustration I suspect you are... well, I live and breath for that stuff."

Well, then you may be just the person I am looking for. I adore the work of John Cuneo, Richard Thompson, William Steig, Lynda Barry, and a small circle of other "intentionally naive" illustrators (for example, Thurber from an earlier generation). I think they are absolutely brilliant. But there is a much larger group that I think is just awful. I do not deny their popularity at all, in fact that is part of the issue. I would not criticize a mediocre talent who was struggling to get along, but anyone who is exhibited in museums as a "master" of comic art and offered up as a lion of culture should be able to withstand a closer look.

For example, I cannot find any redeeming social value in the drawings of Panter, although he has coffee table books proclaiming his greatness. Spiegelman is a terrific writer and has accomplished a lot, but his drawings seem ham handed to me. Alison Bechdel writes a touching story but I don't find that her simplistic drawings add much. I give Chris Ware lots of credit for hard work and sincerity, but his actual drawings (meaning the images inside the box) seem to me mostly stolid, plodding and unimaginative, and I am baffled by the armies of fawning sycophants who find genius in every page.

So yes, "their work is very popular because people like it so much." I certainly don't want to dislike their work, and I would sincerely love to have an intelligent conversation with people who are able see what I am missing. In the past when I have made such a request, I have received responses such as:

"A couple of suggestions for you Dave; grow up & wise up."

and

"Sorry, David, but you have no idea what you're talking about. Go back to reading batman; you're totally out of your depth in trying to understand why Ware is a great artist."

and

"You are completely on crack. I have never seen such a misguided discussion in my life.... the art world is horrifically driven by vacant aetheticisms..."

I'm hoping you can offer me something a little more helpful.

David:

I do not think the question is a moral one - which I assume to be the reason you place the logical extension of the 'anti photo-ref' argument into something like the puritan world of grimly grinding one's own colours.

Rather, I believe the question should be about the degree of synthesis required in the artist's mind as it juices selected raw elements from the world, be they immediate or through the filter of photography.

Gosh, I'm sorry, our preferences as far as those artists are concerned are similar.

I don't like Panter, Spiegelman or Bechdel. I may *hate* Ware, not just because his art is incomprehensibly bad, but he's also an asshole.

If you think I'm simply a fuddy-duddy luddite, then I reallllly haven't been making myself clear.

In fact, I am absolutely the last person to care about "doing things exactly as the old masters did it" for the sake of some imaginary artistic purity or quality that leeches out from the trappings of being an artist. I have no time for such pretension. It is like saying that it is the vocabulary of Shakespeare's day that makes him the writer he is. Or that flowing drapery on a nude is what makes good classical art. Or that good music has violins in it. These are all absurd thoughts that have nothing to do with just how a communication becomes poetry or how meaning can be delivered through the mechanism of aesthetic fictions.

The difference between Cunningham's Island pictures and Homer's Bermuda pictures, is that in the first the effects are more or less limited to feeling of light. Whereas Homer will give you the feel of the light, and the salt in the air, and the movement of the clouds, and the lilt of the waves, their wetness, and many other aspects of the experience both animative and tactile.

Much (most?) contemporary illustration -- the stuff you see compiled in those Taschen books and such -- seems trivial, trite, not very interesting and ... I could keep piling adjectives. A counterpart to all too much postmodern painting and other activities called "art" these days.

I know you were multitasking at the office earlier, David, but what you wrote gives me the impression that you think the trends you (and I) don't like are going to continue. But there have been pendulum swings in history. They don't repeat precisely, but the general sense of moving between extremes can be found. For instance (and I greatly simplify), women's clothing in upper-class circles was risque around 1800, was buttoned down later that century (think "Victorian") and since the 1960s has gotten risque again (though details deffer from 1800 of course). So I see no reason why illustration trends cannot reverse, even in the context of changing communications media. Evidence? We're not talking High Art in this instance, but compare what's shown in the Spectrum (SciFi/Fantasy) annuals with what's in those occasional Taschen compilations. There is much subject matter silliness in both, but then you might be brought up short by an oil painting by Greg Manchess or a digital-art book cover illustration by the likes of Stephan Martiniere.

MORAN-- While I don't hang out at the Society of Illustrators (wrong city) my sense is the same as yours. When Cunningham was elected to the Hall of Fame, he got a lot of respect from peers who had followed his 40 year career. The president of the Society said, "Bob Cunningham has made his indelible mark on the field of illustration with his unique sense of abstract composition, color and use of light....Bob's honesty and humbleness are refreshing in these over-promoted and over-hyped times." I think that last part is the heart of the respect he received: the old Alex Toth admonition, "Make it so simple you can't cheat."

Scruffy-- Those are important distinctions. As you say, "Not the lack of power but power restrained." If you have no power, then restraint isn't really restraint, it's just timidity. (Or as Nietzsche wrote, "I have often laughed at the weaklings who thought themselves good because they had no claws."

In response to Richards comments on Cunningham's work and especially the statement about " it seems more likely that the pleasant simplification in his work is a happy mistaking." It is Richard who is mistaken. Cunningham did use photographs, but only as reference. He would project slides onto a hanging sheet of rear projection screen. This allowed him to bring his subjects into his studio rather than working on site. Then, working more like Degas, he would compose his images first with many black and white sketches followed by color sketches. It's important to note that Cunningham would complete 20 to 40 small thumbnail sketches on simple copy paper and with each sketch he would assess and push the abstraction to its' limits until he achieved the " feeling" that he was seeking. The process was an indefinable one for him and it became more of an organic and intuitive sense of when to know when a painting was complete. Cunningham would use the word feeling because he couldn't define what he was looking for in a finish. Yes, composition, color and simplifying were important elements in his work but drawing was essential. How could someone who care so much about distortion be called a mere copier of photos? Once Cunningham found the sketch that suited him he would disregard his photo reference and work from his sketch.

David's decision to select Cunningham's work was an excellent choice to illustrate the importance of restraint in creating an image. Many of us are drawn to folds, texture and details to illustrate our points of view. But Cunningham's goal was to take away, giving the least or only what was absolutely needed using the simplest shapes and color. He called himself a minimalist.

So, to say that Cunnningham's "work seems not unlike the work my classmates in highschool were making using the photograph-to-grid transfer metho." exhibits a lack of understanding about the complexity of his work. Comparing Cunningham's work to those bad monochromatic, value, grid studies is like comparing a banana to an orange. Is Richard really looking at Cunningham's work? Cunningham had nightmares about people comparing his work to this type of computer filtered artwork Richard used in examples. To think that Cunningham just took photos and edited them down to simple shapes is completely inaccurate. Bob's work is more than a copy of a photograph. Degas, Matisse, Gauguin and Hopper are the artists that fueled him. His studio library included the works of Japanese wood block artists and painters from India.

Most people think Cunningham studied the work of Richard Diebenkorn especially when they see Diebenkorn's city and landscapes from the late 1950's and his 60's, though Bob once told me he wasn't aware of Diebenkorn's work until the 1970's. And when he did see them his wife Jean forbid him to look at them again to avoid being influenced by them and I don't believe there is a Diebenkorn book in his studio. I truly believe these two artists came to the crossroads of their work around the same time without knowledge of each other.

So often we like to credit every illustrator as only being a copier of studio artists. Well in Robert M. Cunningham I think we have a true artist. And If we want to credit his style to anyone, we must give credit and lot of credit to his wife Jean Cunningham, who dared him to take chance. Then Jack Potter, the illustrator whom he studied with at the School of Visual Arts who made him question everything he knew about art. And finally, you would have to list any artist who had the guts to try something different. Those are the artists that Bob looked to for inspiration. And it was guts that allowed Bob to restrain himself and simplify the way he did.

Hi Dave,

I really liked the post because I am not familiar with cunning hams work and was certainly impressed and inspired. The commentary that followed was also thought provoking. And you are a gentleman in your responses. Great posts and I look forward to seeing new ones. I must have come late on this one. It had 25 comments on deck already.

Best wishes,

Amitabh

James,

While Cunningham may not have been looking to gallery work or Diebenkorn for inspiration, his work certainly looks influenced by a great many poster illustrators from earlier in the century, as well as other illustrators and fine artists that were in the air for the previous four decades or so.

Walter Everett, 1930s, check out dem birds and dem waves

For example, the popular and influential Hawthorne/Hensche Cape Cod School of Art, which began early in the 20th century, had all their students do outdoor light studies called “mudheads” until the students learned to see color simply. Hawthorne was one of Rockwell’s teachers. The similarity between these studies and the cunning work in question should be clear...

Mudhead 1

Mudhead 2

Mudhead 3

Mudhead 4

Richard-- I can't claim first hand knowledge of Cunningham or his methods the way James has, so my contribution is mere speculation. Nevertheless, let me offer some reactions to your comments on Cunningham.

You suggest that Cunningham doesn't have the chops to escape the influence of photographs, and you illustrate this point with an image to show, "in his works where the figures are complex, his ability to show them with any elegance collapses." I read your example differently. That picture strikes me as an experiment (probably in keeping with the fashion of the time) to create a flat geometric pattern with no focus on the elegance of the underlying figures. The artificial colors in bold candy stripes seem entirely consistent with the artificial looking figures which are relegated to a tiny, repetitive thread along the bottom of the page. Elegant, naturalistic figures would seem incongruous with the theme of the picture. This suggests that Cunningham's purpose was different from what you suggest (although in my view it was a failed experiment).

In support of my interpretation, I'd offer Cunningham's preliminary drawings of those birds, along with the pencil sketches posted on the Cunningham site I linked. My personal prejudice is that nothing reveals an artist's chops like a pencil and paper, and measured by that standard I think Cunningham shows himself to be a formidable artist with the vertebrae to control tools such as photography.

In another point, you compare Cunningham's work to serigraphs by other artists. This is subtler terrain for me. We are now able to translate a 3 dimensional image (whether painting or photograph) into a series of flat colors through a purely mechanical process. As machines become more sophisticated, the resulting images will get better and better. Whether the gap between human and machine in this area will ever be fully eliminated-- that's part of the unknowable future. But right now, I personally see judgment, taste and creativity in Cunningham's flattening process that I do not see in your examples. I'd say that most (but not all) of your examples could be achieved mechanically but in my view Cunningham's images could not. It's a subtle difference because Cunningham deliberately eschews the kinds of flourishes and garnishes that are easy evidence of human involvement. He strives for the ageless simplicity of Stonehenge, so you have to look for evidence of human taste in less conspicuous choices.

You obviously know what you like and why you like it, and that's great. I'm not trying to persuade you to share my taste in pictures, any more than I would try to persuade you that blue should be your favorite color. But since you took the time and care to dig up some interesting examples and share them with the group (which I appreciate) I thought I should explain my reaction.

chris bennett wrote: "I do not think the question is a moral one."

I agree with you that the artist's juices are paramount, but I also think that moral overtones creep into these discussions because people tend to resent artists who haven't paid their dues. They think it is "cheating" for someone to get credit for results they haven't earned, When Norman Rockwell first began to use photographs, he was publicly accused at the Society of Illustrators of being a "Judas" who had "gone over to the enemy."

Amitabh-- Thanks and welcome.

Richard wrote: "Gosh, I'm sorry, our preferences as far as those artists are concerned are similar. "

Drat. I'll have to keep looking for someone who can explain them to me.

James-- Thank you so much for your interesting and very valuable report on Cunningham's methods. A few words from eye witnesses are far more important than the musings of speculators like me. I appreciate your writing in and sharing such important information.

Donald Pittenger-- I don't know how we "unlearn" technology that makes pictures faster, more efficient, less expensive. Once readers saw the golden, full color pictures of the Saturday Evening Post in the 1930s, I don't know how they could ever return to the wood engravings of Harpers Magazine from the 1850s. Now that they have seen pictures that move and talk and glow on a screen with colors illuminated from within, will they ever be content with those stationary pictures printed with chalky colors on paper magazines? Heck, will there even be paper magazines?

Kev Ferrara-- No, I definitely don't think you are a "fuddy-duddy luddite, " which is why I thought it would concern you when I suggested that you were taking a hard line position which, if followed to its logical conclusion, would land you in the company of the Luddites. If you really think "there is no making peace with photos," and the two photographer/artists I mentioned don't move you, isn't there anyone else who works with photographs that you think crosses the line into significant art? (Notice I don't suggest Warhol.) Finally, and most importantly, I don't think you can fairly dismiss Cunningham as a "tracer-designer." He doesn't show off like Sorolla or Sargent or Brangwyn, but that's part of his charm. He's just different. But as "James" describes, he does a lot of the hard work of art.

David Apatoff wrote: “…but I also think that moral overtones creep into these discussions because people tend to resent artists who haven't paid their dues. They think it is "cheating" for someone to get credit for results they haven't earned…”

Yes, that's true. Unfortunately, this attitude completely derails the premise by which the real argument can be understood. It assumes ‘quantity of knowledge’ is the generator of art, rather than the ability to meaningfully synthesise experience into “the mechanism of aesthetic fictions.” (Kev’s marvellous phrase)

David, you are probably right. I should not have called him a tracer-designer.

Equally unnecessary is your pejorative characterization of Sorolla, Sargent, or Brangwyn as "Show offs." That's like saying that Tolstoy is a show off for not writing Haikus. Or that Rachmaninoff was a showoff for actually composing and orchestrating his ambitious works, rather than just playing a few nice open chords on the piano.

Regarding photographs, I worded what I said fairly carefully. Photographs as the foundation of the composition... that's the issue. Photographs are a wonderful aid, and most of my favorite artists use them. But they are a journalistic tool by nature and as such may assist the artist in his portrayal of the still surface of things.

However, the still surface of things is the quintessential example of a fact that lies. Almost nothing is still. Leaving aside the obvious examples of people and nature. Find the stillest object you know of in your local environment, and put a time lapse camera on it for a day, and you will see the truth of that matter. For light changes even the most iron bound object into a visually active thing. (Only in an underground bunker, shut off from nature completely, will life truly come to a standstill.)

If art is to be about truth, and I think the essence of all great art must be to capture truth, it cannot be about the still surface of things.

This is a basic philosophical thought that has animated, (literally) much of the greatest art we have. (I am excluding floating sharks, broken plates, shit in a can, and red squares from this category. So sue me.)

It has nothing to do with fashion, now versus then, pretension, arrogance, my existence as a western white male, how I was brought up, or much else. It is simply a basic philosophical point.

To see the result of over-reliance on photography, and the resulting stiffness of the art, well... I don't need to give you examples of that. There's a million of them.

To the extent that Cunningham worked from photographic slides in his studio and relied up on them for his compositions and drawing, to that extent is his work is stiff, imo.

To the degree that Cunningham finds colors and shapes to successfully evoke the light of the day and the objects and environmentshe depicts, he is an artist of the first rank, imo.

To the extent that he excluded information about what he was depicting because he could not render it as a graphic design in his particular flat style, to that extent his work is merely a reduction of reality, and not a poetic concision of it, a work of design rather than a work of art.

Btw, your comparison of him to Toth isn't quite as apt as you think. For the great effect of Toth's work was never the individual panel, (which he reduced to the barest essentials), but of the movement between the panels. Toth reduced his work to utter simplicity in order to better tell the story in pure abstract emotions animating over a page. Cunningham's work has no such movement, and no story to tell. It is just reduced for the sake of reduction, for the sake of design.

In my opinion.

Kev Ferrara-- Now that I'm in a place where I can provide a jpg, I'd still be interested in your reaction tothis picture by Matt Mahurin. How does a hybrid like this fits into your theory of photography?

Also, I did not say that Sorolla, Sargent, and Brangwyn were "show offs" (nouns), I said they "showed off" (verb), meaning that their style of painting enabled them to put flourishes in their work that rubbed people's noses in just how damn good they were. One reviewer said, "most of us wish we could do anything as well as John Singer Sargent painted." Each of those guys did a high wire act that gave them ample opportunity to dazzle their audience with mid-air somersaults. But I didn't mean to suggest that occasionally flaunting their talent defined them (as "show offs"), any more than it defined Mozart when he couldn't resist emphasizing his astonishing talent before his competitors. My only point was that Cunningham has a much less flashy, more humble art form. If you want to appreciate what he brings to the table, you won't easily find it in flashy brush work or other conspicuous places.

I do appreciate what he brings to the table David. But four asparagus sprigs, no matter how well prepared, don't constitute a meal.

That Matt Mahurin photo-illustration shocks, makes its meaning plain, and then is exhausted of its mystery, except for the fact that you've seen a man biting into his arm, blood escaping from the wound, and some creepy looking fingers. So your brain has been given a hit of pornography strong enough to daze it for a while. I guess one of the salient characteristic of porn is that it is hard to unsee, once it is seen. Eyes are the windows to the soul, a wise man once wrote.

That this pornography has been used to make an IMPORTANT POLITICAL POINT™ doesn't make it any less pornographic.

It is like those images of diseased organs on cigarette packs, which perform the same function as this photo-allegory. (Those disease photos are surely art in somebody's estimation.)

I suppose you haven't grown up watching as many schlocky horror movies as many of us have. So the sensation of someone biting their own arm off still has the power to arrest you without it registering with you that your are being schlockified (porn-addled).

Once you get over being impressed with the ugly thrill of it, realize there is nothing easier in the world than creating sensation and shock in the audience. It is, as they used to say, cheap.

I wonder where you would draw the line for the use of pornographic sensationalism to make political points that you agree with?

What if a big bag of money was photoshopped so as to seem like it was graphically raping a woman with an American Flag painted on her face? Would that impress as good art?Or would that more readily register with you as being a disgusting way in which a polemicist garners attention to himself while ostensibly making an IMPORTANT POLITICAL POINT™.

kev, I think David likes the image because it is gorgeous.

It's hard to give credit to work that seems to owe such a debt to photography. Even the "composition" feels more like cropping with some minimalist reductions thrown in (or "taken out" more precisely) rather than what I'd consider actual composing. In cases like that, I think it's debatable whether it indicates a laudable, positive artistic skill or is rather just passively avoiding compositional disunity by virtue of the fact that there is less that can go wrong.

Kev Ferrara-- I think most of the people who gather here to discuss these topics do so because they are genuinely moved by the power of images. I for one think that images have the ultimate power: that is, a quality image is self-legitimizing.

It doesn't matter to me if an image is a photograph or pornography-- if it holds its own as an image of quality and substance, then it has earned a seat at the table. I find it too difficult to enforce these miscegenation laws designed to keep out mongrel art forms, such as photo-referenced paintings. Besides, I have a sneaking suspicion that those who insist "there is no making peace with photos" may eventually find themselves encircled and vanquished by photos. The economics seem to dictate it, even if the accelerating pace and the cultural illiteracy of the mass audience did not. If you don't like my Mahurin (and Richard is exactly right, I think it is "gorgeous") are there any photographs anywhere you believe qualify as art?

I recognize that there remain differences in the skill levels between a Sorolla and a school girl randomly snapping pictures with a cell phone, and all of that is very important to the hero worship of the artist. I personally am not immune to worshipping hero artists. But if you don't think that a picture speaks for itself (res ipsa loquitur) you may find yourself on an increasingly complex and troubling path as lines blur and genealogy becomes more inconclusive going forward.

(PS-- for my final blog post, perhaps I will display an assortment of my best pornographic pictures, so get your insults ready).

etc., etc.-- Please note Chris Bennett's comment above, about whether objections to photo-reference are a moral issue. When you say, "It's hard to give credit to work that seems to owe such a debt to photography," are you making a judgment about the worthiness of the artist, and whether they have really earned the credit for the quality of the image?

I heard from an artist who said it used to be hard for him to give credit to Bernie Fuchs when he knew Fuchs relied on photo-reference. Then he watched Fuchs draw in person, without photo-reference, and recognized that Fuchs had paid his dues studying drawing and anatomy, and that Fuchs was in fact a terrific draftsman without photos. Suddenly Fuchs' work was morally transformed in this person's eyes. As long as photo-reference only increased Fuchs' speed and efficiency, making him more productive, and it was not a substitute for basic skills, it became morally OK for Fuchs to use it.

As much as you and I agree on, and there's a whole lot that falls in that category, I don't think we'll ever fall in line on this particular point.

As far as I can tell, your position is this: You may find some image to be of "quality" or "gorgeous" if it strikes you in the right way and resonates with you. This is your sole criteria for quality. If it strikes you, it must be quality. If it doesn't strike you, maybe its just not your thing, or maybe it's actually bad art. But as long as it does strike you, it is art, and it is good.

Chris Ware makes crap art. Art Speigelman makes crap art. Jeff Koons makes crap art. Tracey Emin makes really bad art, so bad in fact that a part of you wants to say that it isn't art. But the other part of you that hates authoritarian judgementalism down to the very marrow of your bones, won't let you consider just why it might not be art, so you leave it be.

That about right?

The possibility that you might like something that is produced by a creative that isn't actually any good is not a thought you consider much.

Wheras, I know I like some stuff that is complete trash, and I know exactly why I like it, and I also think I know exactly why, poetically, aesthetically, philosophically, etc... it is truly crap. I also can live with thinking that Cunningham is a great designer but not much of an artist.

And I realize, again a spot where we differ, that making a distinction between designer and artist is something that you simply cannot get behind.

Meaning is another area where we are at odds.

You understand Mahurin's polemic point in his picture. Therefore you announce that the picture is "meaningful" to you. That the meaning is so blatantly obvious that it can't be missed by a fourth grader doesn't seem to enter into your consideration of just how good a communication it actually is. How artful it is.

To me, this is the art of the editorial page, where meaning must be spoon fed to the masses who must be shown what to think by diagrams. There is nothing worse in art than allegory to me, because, aside from its weakness as art, it is always so bloody obvious. Which means, when I am subject to the work, I am being treated like a schoolboy by a dogmatic, condescending artist who doesn't understand that, according to show biz lore, the audience's IQ shoots up 20 points when they pay attention to a picture.

I suppose the regular pomo gallery-goers need that extra 20, so they don't drool on their gucci handbags.

I find it too difficult to enforce these miscegenation laws designed to keep out mongrel art forms

Yeesh, david. A little heavy handed with the Nazi rhetoric, aren't you? Or are you comparing me to a racist-bigot southerner?

Either way, those are some ill chosen words.

It seems like you are more interested in whether Aesthetics is exclusionary in some way that is anti-democratic, rather than being interested in whether there is something worth learning in aesthetic theory that actually sensibly articulates difference in quality between various kinds of creative works.

It just dawned on me that you don't actually reflexively reject the idea of judging art on a qualitative level. Because you do judge art all the time in just that way. What it really comes to down to for you is rejecting the idea of accepting the existence of objective criteria by which to judge art. Which is tantamount to accepting the postmodernist argument for complete relativism in all cultural products. Which would entail, as well, that any pre-modern aesthetic philosophy must be merely one way of looking at things, and not related in any way to objective reality.

Besides, I have a sneaking suspicion that those who insist "there is no making peace with photos" may eventually find themselves encircled and vanquished by photos.

Are you trying to intimidate me, David? I assure you it won't work. I believe what I believe about art without reference to economic trends, peer pressure, or fashion, or a friend's heartfelt opinion. I'm not a fair weather thinker.

Plus, you say photos will dominate, eh? I say supply and demand makes photos absolutely valueless, except where they capture historical events and can be rented to media outlets and book publishers.

And oh by the way, the winners of the race to make image capturing and image manipulation so easy that even the talentless can make "great images" is Canon and Adobe. All hail Canon and Adobe!

I guess I should also point out that I use photo reference whenever I need it. And I've done hundreds of photo-collage allegories for commercial clientele which has paid many bills, all of which was easy as pie to create, and all of it junk, intrinsically.

Having read this far I think it's time D. Apatoff posted another illustrator's works with comments, please.

If you don't want to contribute to the conversation, Scott, don't. The rest of the Internet surely has something else to interest you while you are waiting for the next post.

Please note Chris Bennett's comment above, about whether objections to photo-reference are a moral issue.

Any "moral" issues would be defined, determined, and trumped by aesthetic issues, therefore (no offense) that is a fairly academic, PCized, and uninteresting line of discussion for me personally. If an artist's work can offer little more than a photograph can offer, then I care little for the art and therefore the artist.

Then how do we distinguish between a photograph and a work of art that looks like one?

The surface of an Ingres resembles a photograph, but it is clearly not a photograph of something that actually existed. Disregarding when they were painted, the same holds true for Van Eyke’s ‘Man with a Turban’ or John Jude Palencar’s “Dearmer”.

What is at the heart of this question is the key to the very nature of what art actually is.

Chris,

But isn't that an aesthetic question rather than a moral one?

Obviously we are operating from two vastly different (and probably irreconcilable) aesthetic viewpoints; I just don't see photography as the defining, point-of-orientation landmark for art in the way it seems to me that you do. Undeniably photography has had tremendous impact upon art in the last 100 years and I'm not denying that...but I consider sculpture and architecture are far more important than photography in the larger scheme of things.

David "The Straw Man" Apatoff

Nobody thinks by using photographs, M. Leone Bracker did his work any favors. (Collier's 1920)

Nobody has heard of Lejaren A. Hiller ~ Cosmopolitan, Volume 57 (June–November, 1914) also; he was a classmate of Harvey Dunn at Th Art Institute of Chicago. …and father of some composer.

&

Everybody likes Saul Tepper ~ The American Magazine, 1935

…but if you don't want to check that baggage, please feel free to carry it.

Etc, etc: “Undeniably photography has had tremendous impact upon art in the last 100 years and I'm not denying that...but I consider sculpture and architecture are far more important than photography in the larger scheme of things.”

I wholeheartedly agree. And I believe the reasons for this are deeply bound into the ‘hands-on’ methodology that the execution of these art forms, by necessity, entail, including painting. I do not mean (and this is where you may be misreading the ‘moral’ point I made earlier) that the traditional ways of hand-making images is essential per se. Rather, that the process of building images from the ground up encourages the mind to synthesise the experience that prompts the undertaking into meaningful pattern. Shoving around layers of reference photos in Photoshop does not encourage this to anywhere near the same extent that manipulating a meaningless plastic mud like coloured pigment or clay does. The reason being the degree of metaphorical engagement with the medium.

However, this does not mean that it precludes the possibility of this happening. My point is that only the most sensitive to the principle I have just outlined, have the chance to achieve it by the proxy, dephysicalised means engendered by the new technologies.

I'm not interested in art at all.

I'm interested in images.

Some images I'm interested in happen to be art, made by artists with a vast wealth of communicative intentions, but more often than not the images I'm interested in are not art at all.

I'm moved by the oak in front of my apartment on a rainy days, my newborn's smile, the old lady next door's hands.

None of these have been made into pieces of art, and if art requires a human artist (if we don't allow for a "god" to be the ultimate author of everything), then these things are not themselves art, but if I had to choose between those things and any piece of human-made art I've ever seen, I'd choose those things.

What's more, my own art is better when I'm focused on image, with or without author, than with art with authors. I think that's pretty universal. Artists who are concerned with Art not images, tend to produce a steady stream of garbage.

Richard:

It’s a truism that a mother’s snaps of her newborn are more important and cherished by her than owning any of the world’s great masterpieces.

And another truism is that art for art’s sake is empty mannerism.

"a mother’s snaps of her newborn are more important and cherished by her than owning any of the world’s great masterpieces."

I'll take it a step farther, and say that a mother and her snaps of her newborn are more important and cherished to me than any of the world's great masterpieces.

Isn't all this talk of Art exhausting though? Doesn't anyone want to talk about images?

अर्जुन

Great stuff! Jeez, I've been looking for an example of Tepper's photo illustration forever. Thanks for finding that. And boy, does it suck! :) And that Hiller is a classic! It reminds me of some of Maxfield Parrish's weaker stuff where the figures look like colored photos cut out and pasted onto his paintings.

Richard,

I share your love of images. I've only come to the question of art because of my love and research into image-making.

I've found that the best images are works of great art

Images that seem strong at first, if not great art, will tend to lose their allure. I've seen a million photos that seemed to be strong images at first glance, only to find that they had nothing deeper to say than what was apprehended consciously in the first seconds of viewing.

The real issue is just how much of the image is infused with visual subtext. And how generalized the subtext is to the composition as a whole. So it all contributes to and resonates with a singular idea. This is an imaginative, compositional matter, it can't be captured mechanically or abstracted from a photo. It must come from the heart via the poetic imagination. And it must be read by the heart of the viewer. It can't be so obvious that the intellect can read it, like an allegory/text.

I'm impressed by the idea that a piece of art like that could exist.

I agree that it could.

I have not myself experienced it, I find that art generally dies the same death that photographs do after a few views, and quite often much faster (except where I'm impressed by the artist, but that's not really about the image at all, that's that art hero-worship).

To make it clear, the greatest image I have ever seen was Hubble Deep Field, a photograph. It has the most repeat value of any image I've ever seen, and what's more, I don't see how a painter, with all of the greatest of communicative intentions, could anything to it as an image at all.

*could add anything to it

ScottLoar-- Sounds like you're a member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Dead Horses. That's a good club to belong to.

Kev Ferrara-- I don't think there's much chance that either of us will find ourselves at the extreme ends of the spectrum. You're not going to end up cloistered in a monastery in Florence for purists who grind their own pigments, and I will never throw the floodgates open wide enough to accept Tracey Emin. Alas, we're both in that undramatic middle ground where reasonable people can agree on some things and not on others.

I think you're right, my own love of art is fueled by the pictures that "resonate" with me, rather than pictures that fall within a particular set of rational criteria (for example, non-photo-referenced paintings that demonstrate manual dexterity). I confess that the raw titillation that comes from lovely images is what keeps me up at 2:00 am, reaching for another book. I of course agree we have a responsibility to use our intellects to try to understand what we like and don't like about images, and why. And if we're going to jabber about pictures in places like this, we have a responsibility to look for a common (moderate) vocabulary, hopefully in the interests of maximizing the appreciation for the pictures that move us.

But when it comes to "knowing exactly why" I'll like the next picture (or photograph)," I've discovered that the unknowable is always hiding around the corner, licking its chops (http://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2012/02/happy-valentines-day.html) That potential for ambush is part of the delight of this whole enterprise for me.

P.S.-- speaking of "moderate" language, my term "miscegenation" wasn't intended to label you a "Nazi" but it does strike me as a useful term for those who become too concerned about the pure blood of Art commingled with the impure blood of photography.

etc, etc. wrote: " If an artist's work can offer little more than a photograph can offer, then I care little for the art and therefore the artist."

I suppose that means you have never cared more than a little for any photograph or photographer? On the "morality" issue, if a photographer takes a picture of a person with a haunting gaze (for example, Steve McCurry's "Afghan girl" from the cover of the National Geographic) I can see why that is morally different from an artist capturing a haunting gaze in a painting, but as a physical object is the photograph's composition any worse, or the gaze any less haunting, or the thoughts it provokes about the human condition any less profound?

"And another truism is that art for art’s sake is empty mannerism."

Chris, what purpose is your own art for ?

I'm just going to repeat myself, hahaha.

Hubble Deep Field is the greatest image of all time, and it is a photograph.

Can we take a moment to talk about images for a moment. This is a particularly great one.

It's only 3 arcminutes across, meaning it's an image of roughly 1/24-millionth of the sky. That's the size of a 1x1mm square piece of paper held at a meter's distance.

What's it a picture of? Galaxies. A ton of them.

Each with an estimated average of 400 billion stars. Each with an estimated average of one planet.

I really don't understand how anyone can talk trash on photography, when Hubble is just a super-fancy camera.

David,

I like photography enough to have spent several thousand dollars on Canon L lenses. However, Kant's Critique of Judgment is so deeply ingrained into my thinking that it is now impossible for me not to differentiate between judgments of the good, the agreeable, the sublime, and the beautiful. Once you recognize they are not the same, discussions like this are about as amusing as watching a shell game.

Richard,

the Hubble image in itself isn't visually interesting. no more so than glitter wrapping paper, or a firework display (which is what the universe is anyway, only cooled and solidified).

i assume you only think it's the 'greatest image of all time' because of its scientific newness. it will be old hat in a couple more decades, when newer lenses see light rays from further

away.

Richard-- I am not sure the Hubble Deep Field is as great as the pillars of creation, but I think both of them are astonishing, stirring, inspirational images. I find the pillars of creation as sacred as any Renaissance altarpiece. These images played a major role in opening up my earlier prejudices against photography. Res ipsa loquitur.

Laurence-

"the Hubble image in itself isn't visually interesting"

No image in itself is visually interesting. Without a human to understand and interpret them, images are dull as can be, whether it be photograph or painting.

"i assume you only think it's the 'greatest image of all time' because of its scientific newness."

No, I think it's the greatest image of all time because it illuminates where we live in a way no other image has.

Looking at it I simultaneously feel that my size approaches zero, that reality has the metaphysical buoyancy of ∞, I become connected to a universe of infinite other strange and sentient beings and worlds, I am drawn into a depth of mystery about existence that I find no where else, and there in the darkness of that mystery I am touched by faith for something quite like God, only stranger.

Simply, it fills me with a sublime rapture that no other image has ever come close, and it does that so simply. It does it more simply than any other image ever has -- it certainly beats the pants off Cunningham. To quote scruffy "In spiritual terms, we call that humility or meekness. Not the lack of power but power restrained."

"Without a human to understand and interpret them, images are dull as can be, whether it be photograph or painting."

Richard,

you seem to be implying that the eye isn't naturally drawn to one pleasing visual aspect or another unless the 'image' in question embodies some sort of symbolic meaning ?

would that include surface textures, colours, light levels ?

i would counter that the world of surface and texture is full of indescribably beautiful detail... just look at a an electron microscope photo of a carpet bug for example.

Simply, it fills me with a sublime rapture that no other image has ever come close, and it does that so simply. It does it more simply than any other image ever has

Richard,

If you didn't know what you were looking at, and didn't already have a profound understanding of the truth of how vast reality, that photo would just be a curiosity to you. Like it would to a monkey or a baby.

The difference between art and that kind of journlism is that art, at its best, supplies the understanding. That is its truth value. In art, it is expected that you already know the facts, and you are provided truth.

In journalism and scientific photography for better or worse, you are expected to know the truth first, in order to appreciate the facts shown in the image.

Raise your hand if you don't understand that distinction.

Laurence John: Chris, what purpose is your own art for ?

To make others feel as I feel. Because I believe that deep, deep down, below the accidentals of life’s surface, what others feel is also what I feel. So I try to put together something that has all the relevant information contained within itself and requiring no outside associations other than our human commonality in order to read it. So that, because of its completeness within its own self-inferred rules, will, to those prepared to give themselves to it, hopefully communicate a sentient resolution of this feeling. The purpose of this. A flower releases its pollen. So it is we need to share what little fruits we may have.

But I’d like to add that in my opinion I have achieved this only a handful of times. If that.

Those who have achieved this ideal consistently would be, off the top of my head: Michelangelo, Maillol, Constable, late Titian, Velasquez, Chardin and Mark Shields.

The Hubble deep space image requires knowledge of what represents to be impressive. Otherwise it might just as well be a snap of some pretty firework going off. Michelangelo's Pieta affects me regardless of its iconography.

Point being that the Wonder Value™ of that space image is not intrinsic to it.

So when somebody says that art has intrinsic value, what they are trying to say is that its value lies in its ability to express truth aesthetically as an experience of the image.

A journalistic photo has surface value, in that it shows facts, which are the texture of the reality. Facts are not intrinsic values. There is no photo that can be experienced as having an intrinsic truth value that is expressed aesthetically.

(Need I point out, in passing, that if Pillars of Creation ™ were not so photo-manipulated and were called something like "Really Big Space Dust Clouds" it wouldn't have nearly the effect upon the psyche. And of course, again, if you didn't have an appreciation of the vastness of interstellar space, you might assume the image was taken with an underwater camera in a murky swamp in Louisiana. )

" So I try to put together something that has all the relevant information contained within itself and requiring no outside associations other than our human commonality in order to read it. [...] Michelangelo,"

The Sistine Chapel, to the Oromo of East Africa, circa 500 years ago, would be nothing but a bunch of nonsense. I suspect, having never seen a white-man, the figures would be barely even recognizable as such, and that's if art were only a human endeavor, but as Hubble has made plain, chances are there are countless sentient species in the universe -- if art must be universal, ought it not speak to them as well, and if we were to show them Michelangelo and Hubble Deep Field, which do you think they'd connect with?

but as Hubble has made plain, chances are there are countless sentient species in the universe

Again, the hubble images show nothing of the kind. That is all speculative information you are bringing to your experience of the photo from outside the information actually contained in the image.

See my previous posts.

I agree that to the Oromo, The Sistine Chapel would be mostly nonsense. Because, again, the sistine chapel, as a work of visual art, is allegorical. And as such is a tribal, textual communication. Which means it is not universal.

Some aspects of it, would still impress, I am sure. For instance, its vastness. The two figures touching is a nice piece of imagery, too.

And I think if the Oromo actually made it to the Vatican, they would recognize the images of white people. (The drawing and painting isn't that bad.)

As much as I admire Kant, I always felt that persistent questioners such as Socrates get us closer to a livable version of the truth than Teutonic systems builders.

I appreciate the human temptation to codify (I see it in state legislatures all the time) but if you look over the last several comments and you'll see absolute truths ricocheting off the walls like bullets at a Saturday night mixer between the Crips and the Bloods.

How to reconcile all these universal (but mutually inconsistent) truths? Personally, I don't understand how we can decry photography for its lowly journalism, yet laud illustration (or other representational art) for the narrative it conveys. I don't understand how we can say the value of the Hubble photographs lies in our outside knowledge of its meaning, yet we manage to appreciate ancient Egyptian art without the faintest clue what those hieroglyphs mean. I don't know how we can fault the human processing of the Pillars of Creation, but fault other photographs for their absence of human touch.

If you want to see how photography overlaps with Art, I'd suggest we take a look at art's reaction to photography: do you think that the esteem for skill in the arts would not have fallen over the past century if it weren't for photography? Do you think that artists would have stopped recording historical battles and painting portraits if it weren't for photography filling the same roles? Do you think that artists such as Frazetta and Phil Hale would be painting their cinematic paintings, showing the blur of movement and the impacts that photography has revealed to us, if it weren't for photography?

I don't know how some of the commenters feel comfortable compartmentalizing the two as completely as they do, but I can tell this topic has become a little unwieldy for the comment section of a blog, and I will try to open this up in a new post.

Richard: "The Sistine Chapel, to the Oromo of East Africa, circa 500 years ago, would be nothing but a bunch of nonsense."

I can’t speak for the Oromo, but I agree with Kev’s caveat concerning my point. I am talking about what is there when the allegory and journalism is skimmed off.

When I was nine, my school took me to the British Museum to see the Elgin Marbles. At this stage I’m about as near to your Oromo example as I’m ever likely to be – a modern working class lad who knows jack shit about ancient mythology other than my vague notions from ‘Jason and the Argonauts’ and the Hercules movies my dad took me to see. But I remember the effect those marbles had on me… That assembly of weird stone-shaped bodies was like a frozen wave, dead and alive at the same time. I was looking at some compelling game of ordered stone, a silent music of mass; heaving, swinging, tumbling, pushing, leaning and tying. But resembling people.

Gazing over that group of figures, they were like cams turning in my mind; setting off back engineered movements in my human psyche that reciprocated whatever those who fashioned it were feeling.

That feeling of resonance was utterly different, and was quite separate, from whatever feelings I had from information, however fascinating, awesome and significant, I was to later learn about what these figures carved from Mediterranean metamorphic rock had to do with the belief system of one of the ancient cradles of modern civilisation.

The difference between a lecture on wind dynamics and seeing a yacht straining under full sail.

How to reconcile all these universal (but mutually inconsistent) truths?

That's exactly what Kant's system does for me. The problem for most people is that it elevates formalism (see Chris' elegant description of his reaction to the Elgin Marbles above) to a position of aesthetic preeminence.

Chris,

That was an extraordinarily insightful post that expresses everything I have been trying to argue on various art forums for years. May I quote you? Thank you.

Wherein I respond point by point to David going death-blossom...

As much as I admire Kant, I always felt that persistent questioners such as Socrates get us closer to a livable version of the truth than Teutonic systems builders.

Socrates did not think that truth was merely relative or merely subjective.

Personally, I don't understand how we can decry photography for its lowly journalism, yet laud illustration (or other representational art) for the narrative it conveys.

It isn’t a question of decrying or lowering photography or lauding illustration. It is simply the basic philosophical matter of distinguishing between art, design, text, allegory, journalism, and something we might call sensationalism. The word “Art” to me is not simply an honorific that is bestowed on work we enjoy, anymore than Doctor is an honorific bestowed on anybody that cares for people.

I don't understand how we can say the value of the Hubble photographs lies in our outside knowledge of its meaning, yet we manage to appreciate ancient Egyptian art without the faintest clue what those hieroglyphs mean.

You are wildly conflating things.

Let us compare the two purely at the level of design.

The Hubble photograph linked in this conversation has a rather repetitive yet randomized design to it, a host of small, helter-skelter light blurs in various shapes and directions on a black ground. There is just as much discontinuity as continuity. There is no conservation of shapes, or angles. The color is uninteresting. There is no natural movement to the picture. The eye just investigates as it wishes.

Ancient Egyptian designs have enormous decorative value, with order, rhythm, patterns of pleasing abstracted cartoon pictographs which recur in different forms (theme and variation), complex structure, yet not overly complex, it has continuity, style, authority, craftsmanship, etc. If you look at a basic manual on design, you will find that egyptian art hits all the principles usually espoused and more.

It is blindingly obvious that Egyptian heiroglyphs have an enormous amount to appreciate just at the level of conscious surface design. Equally obvious, the Hubble photo is completely unconscious in terms of surface design. It is a photo of what is. But we really don’t know what it is, unless we already know what it is. Because the non-design of it offers no insight into what the image is actually of or what it portends.

I don't know how we can fault the human processing of the Pillars of Creation, but fault other photographs for their absence of human touch.

Journalism should be factually accurate, David. What value does it have if not to provide fact? (Or are you going to defend the Fauxtography of the Iranian regime circa 2006?)

Secondly, art should be artful, shouldn’t it? So where photos are journalism, they should be accurate and not doctored, and where they try to be art, they should aspire to be crafted from the heart.

do you think that the esteem for skill in the arts would not have fallen over the past century if it weren't for photography?

Mimesis is a technical skill. Where art is lauded for its ability to mimic the frozen look of reality, like a photo, you will find sedulous apes doing the appreciating. Who care what those people think?

Do you think that artists would have stopped recording historical battles and painting portraits if it weren't for photography filling the same roles?Do you think that artists such as Frazetta and Phil Hale would be painting their cinematic paintings, showing the blur of movement and the impacts that photography has revealed to us, if it weren't for photography?

Blurs appeared in action art before photographs, David. And only Phil Hale really uses blurs often. Fyi, blurs are usually only an index of movement (in the context of a knowledge of photography), they are rarely an expression of movement. So it is not blurs, (nor any other information gotten from photographs), that make art come alive. Yes, some of what was revealed in Muybridge’s (and others’) stop-motion photography has assisted the action artist. Same with footage of action in films and on television. But action in art is actually a compositional matter, born from long-term research and understanding by talented artists of how the human eye can be made to move over the surface of a canvas, and how action can be suggested to the human mind subliminally.

Etc, etc: “That was an extraordinarily insightful post that expresses everything I have been trying to argue on various art forums for years. May I quote you? Thank you.”

Of course - it’s very thoughtful of you to ask. And thank you for your kind words.

I recently saw a marvellous BBC programme on clockwork automata by Simon Sharma which mentioned the cam as the engineering heart of these mechanisms. The idea struck me that the cam is, in essence, a component that translates meaningless, unchanging, eventless, smooth circular motion into meaningful, changing, eventful, ‘rough’ multi-linear motion. In other words; into the motion of ‘life-like’ form.

It then occurred to me that words in a sentence can be likened to the bumps on a complex cam. Turned through our mind through reading it, they translate the reader’s baseline consciousness into a rollercoaster facsimile of experience. And the same happens in the process of beholding aesthetic form.

On a metaphysical scale, the smoothness of the big bang singularity ‘roughed up’ into the universe – the birthplace of consciousness that made and looks at that Hubble image. But the human-scale, direct manifestation of this process is subliminally and therefore most deeply experienced by us every time aesthetic form in art, music or literature is witnessed. Art; the emotional cam of consciousness…? Maybe.

Chris,

most artists who produce personal, self motivated art (not commercial commissions for a specific purpose, not espousing some doctrine or other) would say something nearly identical to what you've said which is basically to 'connect with whoever will connect with it'.

and they will usually continue to produce the work whether it makes them any money or not 'for the love of it'... to me, that is 'art for art's sake' so i'm confused as to why you associate that phrase with 'empty mannerism'.

Laurence,

The fact that a non-commissioned artist chooses his own subjects and a commissioned artist does not, has nothing to do with it, in my view. One applies the highest standards of care and intensity whether painting someone’s pet dog, the Queen of England, an IronMan cover or beautiful girls in blue dresses running down some stone steps.

Although every artist has a diet of art as part of their profession and is therefore a product of what they eat in this regard, the real question is one regarding how they themselves choose to cook.

One cannot shake off knowledge, nor is it helpful to do so. But there is a vital distinction between what is made as a distillation prompted by life experience, and something concocted solely out of the experience of looking at art. The Rococo period is a prime example, or the latter works of Picasso. And whether the subject in one’s hands is commissioned or self-chosen, the vital difference between a work that is a meaningful distillation of experience and one that is empty mannerism is entirely contingent upon which attitude is emphasised in the artist while working.

Remember Laurence, most of the art in museums was made to commission! The fact that this state of affairs stopped around the middle of the 19th century is an economic and cultural issue, not a qualitative or artistically moral one.

Chris,

what you've just described sounds like the kind of modern art that can only exist by referring to other modern art.

if that's what you mean by 'art for art's sake' then i have no problem with your definition.

... i don't think that's what Whistler meant though.

Etc. etc.

Critique of Judgment is an early draft of aesthetic theory. Much of it didn't hold up. Why do you embrace it so adamantly?

It is like saying that Newton is all you need to know about physics.

What of terrible art, and great photography?

Can Hockney, Alexander Boguslawski, or Martin Kippenberger hold any candle to the best work of Matt Wilson, Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk, Jessica Eaton , Christy Lee Rodgers, Akihiko Miyoshi,Amani Willet,Caroline Mackintosh.

Surely there is a middle ground by which you'd agree that some photography is better than some painting, no?

Photography is a damned new art-form, are y'all sure you're not jumping to conclusions merely because the medium is new, and so it hasn't been explored in great depth yet?

Sorry to triple-post, but, I'd also like to note...