"To live is to war with trolls." --Ibsen

Talented illustrator Austin Briggs painted a NY Giants baseball game for the April 22, 1950 cover of the Saturday Evening Post.

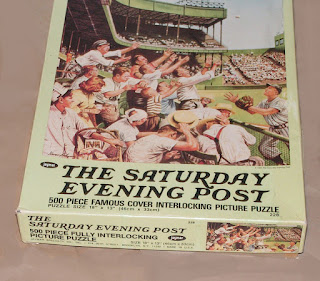

This is not that painting:

Briggs' cover included an African American woman in the crowd. When he delivered the painting to The Post, the editors ordered him to remove her. Infuriated, Briggs refused. He broke the painting in half over his knee and stormed out.

As reported in the Westport blog 06880, Briggs' model for the woman was Fanny Drain, a long time employee of the Briggs family. Briggs' son recalled:

When the Giants were playing she and my father-- whose studio was at home-- would follow the radio broadcasts avidly and vocally; her pride and pleasure in being included in the cover painting were deep.The Post quickly found another illustrator, Steven Dohanos, to repaint Briggs' cover, replacing the African American woman with a white male (the one with a handkerchief on his head). That is the final version you see above.

The Post loved the result so much, they even released the all white version as a jigsaw puzzle for wholesome families to play.

Briggs' gesture of defiance was expensive for his family, but once the cover was destroyed, there was no going back. Briggs never regretted his decision.

It is difficult to imagine such an impetuous act of conscience occurring today. If he was painting today, Briggs would no longer be able to break his picture over his knee because the digital art would've been emailed to the magazine, with multiple copies on his hard drive at home. The Saturday Evening Post would not have to ask Briggs to paint out the African American woman; they would Photoshop a white complexion on her without the artist's permission in 30 seconds.

The wonderful efficiencies of Photoshop help eliminate some of the nasty moral choices that once confronted an artist. We live in a much more efficient world today. But in the words of Epicetus, "It is difficulties that show what men are."

39 comments:

I have a new artist that I hadn't heard of, to admire this morning (Briggs), and a lot less respect for the Saturday Evening Post... Thanks for sharing this story!

Nice story, like always, but we could add that today the Saturday Evening Post wouldn't ask Briggs to remove the African American woman. Even being far from perfect, our world is not only more efficient, but also a lot more equitable.

Good post!

@Javier, the point I believe isn't the actual issue faced by Briggs in this anecdote, but rather the the efficacy of action in the present day means one is less likely to stick to convictions/strongly held beliefs when faced with a dilemma. When betraying them for some other incentive is a click away its more difficult to stick by them. Hopefully no one has to face the same issues Briggs faced, but there's plenty of issues we face every day.

Discuss.

Great post. Too often today I hear the pro's brag about the concessions they make to keep getting work even when it goes against their own judgement.I guess digital has taken most peoples backbones along with their self respect.

"It is difficult to imagine such an impetuous act of conscience occurring today." At first thought we often think that, but fortunately is does happen. Though we don't hear about it until time has passed. There are always people of conscience and morals. As Mr Rogers says "there will always be helpers."

I wonder if Briggs would've reacted like that if it wasn't personal, which is to say, the crux of his indignation being that it was a portrait of a friend. Had it not been, would he have just altered the art?

also

Just looked through 500 Briggs', other than various "natives", I only found 2 that depict blacks, even though there was plenty of crowd scenes in which he could have snuck one into. #1 and #2

I'm guessing that the difference with the cover Kev links to is that it shows the woman and child in their "proper place", working in the kitchen and poor, not as in the Briggs painting at leisure mixing with their betters.

David, i think you're over simplifying the case against Photoshop.

today an artist could pull out of a commission on 'editorial differences' without having to literally destroy the artwork.

i don't think that moral disagreements, fall outs or tantrums have gone away simply because of the digital age.

it's true that an area of hue could be altered easily, but re-drawing something would require that:

-the art department of the magazine / client have a draughtsman at least as skilled as the hypothetical artist.

-they have the same tools (digital or otherwise) that the artist used.

-they're happy to upset the hypothetical artist by altering their work without permission, and potentially ruin the working relationship.

Katherine Thomas and Lucas Ferreyra-- Many thanks.

Javier and Conor Hughes-- I agree that the world is a more open, diverse place today than it was in 1950, and that is definitely a good thing. I suspect that the Saturday Evening Post preserved its huge nationwide readership by being bland and focusing on certain "universal" American characteristics. I understand why the editors didn't want to rock any boats. But that audience fragmented a long time ago.

Kev Ferrara-- The first point that jumps out at me is that Leyendecker is one hell of a painter. But I assume you intend a different point: that that blacks could have a starring role on the cover of the Post as long as they were Pullman Porters or fat mammies.

Armand Cabrera-- Yes, we do get attached to our creature comforts. It is now so easy to make changes on a digital picture you barely feel the pain. By comparison, think of how much more cumbersome and time consuming it was for Briggs to complete the painting, let the paint dry, and go all the way from Westport to Philadelphia to deliver it. The one offsetting advantage is that you get to look the devil in the eye and understand your moral choice better when you get to Philadelphia. With e-mail, it is much easier to mull over what you could buy with the fee for that cover.

Bruce Docker-- I agree. We think that moral questions are rarely presented to us today in such stark, black and white terms. We say that a war against the Nazis was an easy choice, but that everything is more complex today and it is hard to find a "good war." I suspect that these clear moral choices seemed quite slippery to many at the time, and only became obvious in the rectifying mirror of history. Those "helpers" Mr. Rogers refers to deserve to be remembered.

अर्जुन-- I'm sure that Briggs' personal relationship played a role in his emphatic response, although isn't that how all unwarranted biases begin to crumble-- when you know someone personally who doesn't fit the stereotype, and who you feel is worth going out on a limb for? Remember, when this issue of the Post came out, blacks were not allowed to eat in the U.S. Supreme Court cafeteria. So Briggs really was a profile in courage.

Kellie-- Agreed, although I would not call Kev's Leyendecker cover racist. It's much classier than that.

Laurence John-- I didn't mean to blame our tools (and Photoshop is surely an excellent tool) for the weakening of the will and the moral abdication that often seem to accompany our dependence those tools. We can't imagine life without air conditioning today, but people lived without it for 40,000 years before it came along, and just toughed it out. I just think the tools that cushion us from a lot of nature's trade offs and inconveniences also cushion us from some moral choices.

As for your point about a presumptuous art department altering work without permission, I have heard from artists who claim that happens more and more frequently these days. It is so easy to change the color of that short or move the puppy dog to the left side of the picture, it happens all the time (until the artist becomes a big shot and can push back.)

I remember Bernie Fuchs telling the story of the first time a client asked him to sign an illustration. They had to ship the painting back to him, he signed it and returned it, the client received it and was horrified to see that his signature looked like a swear word, so they shipped it back to him again and he painted it out. That added weeks. It wouldn't happen that way today.

D.A. said, "it happens all the time (until the artist becomes a big shot and can push back.)""

"when a client transformed–what would turn out to be my last illustration assignment–into a Photoshop hack job. They rearranged the elements, added a new background and turned a fully rendered figure into a black silhouette–which was embossed in the printing." ~ Marvin Mattelson (a TIME magazine cover artist)

quote from ~ http://blog.fineartportrait.com/put-on-your-thinking-beret-strategically/

That's a very diappointing story. I had never considered the SEP to be so covertly racist and to my mind shows a fragment of truth behind an American myth.

I think Briggs was a terrific draftsman and I admire his response but I think it was a very average cover.

I'm not sure Dohanos emerges too well.

अर्जुन -- As I said, it happens all the time, even when the artist becomes a big shot and can push back.

That's an amazing story about Mattelson (who has a nice blog, by the way. Thanks for the link.) Sounds like it is time to update Al Dorne's code of conduct for the graphics art industry. I have heard other crazy stories-- for example that in the failing bookstore world, retail chains have developed great databases about the kinds of covers that sell, and the chains pressure publishers to photoshop changes in their covers as a quid pro quo for ordering more books.

It would be interesting to collect more anecdotes on this issue. Anyone got any more?

Drew-- I agree, this cover is not my favorite either (apparently Dohanos' cover was virtually identical to Briggs' but with a few strategic changes). But it was very popular as you can tell from the puzzle.

We seem to be without sufficient information to know whether Briggs was asked to remove the African American lady because the editors were racist. Or because most of the Saturday Evening Post's readership were white and, like any people under the sun, are subconsciously more likely to be interested and comfortable in seeing their own faces and lives reflected on their periodical purchases rather than the reflections of The Other/minorities.

It is quite possible that the Post's editors had paid close attention to circulation and sales figures through the years and found a drop off when African Americans appeared on their covers. Which would mean angry advertisers.

The requested editorial change may have been a business decision.

By the way, given that Briggs employed a African American in his home, as domestic help, it is doubtful he would have felt much of a tinge of guilt at seeing African Americans portrayed in domestic help situations in illustrations of prior years. That would have been a standard thing in the culture. But times were changing, if slowly.

Unless there are facts yet to come to light about this story, (Overt racist comments from SEP editors, Briggs crusading for racial equality in some other circumstance, etc.) it seems slightly less obvious to me that Briggs was in a moral rage when he broke his canvas in half.

Frustration at having his art subject to the requirement of the bean counters may have been the main issue. Also that he was now in a very awkward situation with his maid/house lady who he had promised "stardom" on the cover of big time national magazine and now he had to bring her the hurtful news which would obviously be a great disappointment to her.

This is not to say that your version of events could not still be the real story, David.

Kev Ferrara-- In this case, we can be pretty confident of the back story. If you look at bound volumes of the Saturday Evening Post in the 1920s through the 1940s, there were blatantly racist stories and pictures in almost every issue. (Sometimes on almost every page). By the 1950s they had tuned down the more extreme stereotypes, but the Post was still like restricted country clubs or restaurants: it would be gauche in that era to come right out and say, "no negroes allowed," (I'm sure the editors did not say that) but they made it quite obvious where "that kind" wasn't welcome.

The Post's editorial restrictions were well documented in connection with Norman Rockwell, who increasingly chafed under their policies in the 1950s. The book, "Norman Rockwell: The Underside of Innocence" quotes contemporaries on how Norman Rockwell finally quit the Post in 1963 after 40 years because the Post's "censorship" was incompatible with Rockwell's growing commitment to "desegregation and racial justice." Free from the Post's restrictions, Rockwell immediately did several paintings with sympathetic treatments of African Americans for Look Magazine and other publications(famously including "The Problem We All Live With" -- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Problem_We_All_Live_With). The Rockwell Museum also has some important material about this on their web site (http://www.nrm.org/2012/08/new-perspectives-the-problem-we-all-live-with/).

I'm sure as you say that the Post's decision was partially economic (read on the Rockwell Museum's site the extraordinary hate mail Rockwell received when he started treating negroes with dignity) but for me that makes Briggs' act all the more commendable.

One of the best and most powerful pieces of moral writing I have ever read is a 1960s commencement address by Milton Mayer (http://www.junkfoodforthought.com/long/Mayer_CommencementAddress.htm). Mayer talks about how we master the art of self-deception in order to preserve our jobs, and how people use deliberately vague language when asking us to do immoral things so that we can pretend we don't really know the reason we're doing it. For me, Mayer's story about dining with his wife in a Jim Crow restaurant is exactly the story of Briggs at the Saturday Evening Post, and Briggs' reaction should not be underestimated.

Hey David,

I’ve heard quite a number of times about the bigotry at the Saturday Evening Post. And I am in no way defending the post’s bigotry, when it is indeed bigoted. I am more trying to combat the facile blanket condemnation of the magazine, or a view of american society which does not take into account the unconsciousness of most bigotry, or the social realities of the bygone eras we are peeking back into. The last thing I want is for people to suddenly decide they aren’t going to look at Dunn, Leyendecker, and Rockwell, Gruger, and all the other great post illustrators because they worked for that damn racist rag! Given the Hatfield-McCoy way most kids are programmed to think about politics nowadays, a complete dismissal of the entire golden age of illustration as racist would come as no surprise to me.

To the substance of the question; It jams my gears that, for example, I’ve seen several articles where the heroism of African Americans in wartime and in civilian life has been portrayed in the magazine. And then you’ll find an ad with white kids in blackface. There is no simple way to comprehend both of these items in the same magazine, editorially.

(Incidentally, given that golden age illustration was filled with endless caricatures, “types” and facial exaggerations, I think we need to distinguish between caricatures of african americans that were comical stereotypes in the vein of all the rest of the stereotyping going on, versus caricatures that were virulent and hateful in nature. I realize this is a slippery line to define and that many hard liners will simply refuse to acknowledge that there is a distinction there. But I think there is a distinction worth preserving.)

More gear jamming: I’ve read articles in the Saturday Evening Post such as this one by Hodding Carter from 1946, the same year he won a Pulitzer for editorial writing.

The article is fascinating and can’t be skimmed as it only yeilds its meaning as it goes on. It is a complicating article, if it indeed reflects a sentiment shared by the post’s editors who published it. The service the article intends is anti-bigotry, coupled with a plea for more understanding about the deeply entrenched problems of the South which led many, including the author, to advocate for slow change from within. The gear jamming comes from the fact that, at the same time as advocating for tolerance, it will also offer, from our perspective, points that are clearly bigoted. (Also, for some, "slow change" was equivalent to no change. And thus the slow change position itself is a disguised bigotry.)

I still think it a real possibility that what Briggs came up against regarding this cover was a product of the demands of the advertisers for presenting the most salable magazine possible to a largely white audience.

Thanks for the link to the Milton Mayer address. I had already read that, so I’ll just recommend it to anybody who hasn’t.

I think kev and david have halves of the picture here. The profit motive was very likely at base the reason for the editorial decision, however the editors were probably hired in part for having the most popular prejudices of their day, and that is a certain type of tacit racism.

By the same token, I don't think the recent miscegenation (is it unacceptable to use that word?) Cheerios commercial, which has become such a to-do, has anything to do with politically motivated advertisers, but is really just a reflection of their advertising staff. And their advertising staff are a reflection o the prejudices of the market. To make that point more clear, notice that no major advertisers are supporting android rights, pigs/cetaceans as non-human persons, or the rights of any other possible future civil right's issues, just those the market asks for.

Kev Ferrara-- That was a fascinating essay by Hodding Carter, many thanks. I wanted to take the time to read it all the way through.

His description of the southerner's understandable resentment against the Yankee communists looking over his shoulder, and the importance of giving people time to make a slow change from within, reminds me of the famous recording of JFK's agonized phone call with Mississippi governor Ross Barnett on September 29, 1962 . Kennedy was trying to carry out a court order that a negro (James Meredith) be enrolled in a Mississippi school, and Barnett kept saying that if the federal government tried to force the issue, it would just lead to all kinds of trouble. Barnett told Kennedy to wait until things cooled down, and Kennedy at first seemed optimistic they could reach a deal and avoid violence. But every time Kennedy pressed Barnett for a commitment about how long Kennedy would have to wait, the wily old racist danced out of range, and refused to say that he would ever enroll the student. And you can hear the disappointment in Kennedy's voice as he gradually realizes that Barnett is just jerking him around, and that force will be unavoidable. I know Barnett's agenda wasn't Carter's agenda, but 15 years after Carter's insightful essay it was still the agenda of far too many people in power.

As for your larger point, I fully agree that we always have to struggle against Manichaean extremes; the Post achieved many great things and should not be dismissed with "facile blanket condemnation." Those artists you mention (Dunn, etc.) I love their work and return to the Post often to be enriched by them. The same could be said for the writers in the Post. The same could be said for the great caricatures, “types” and facial exaggerations that appeared over the years. I love A.B. Frost's caricatures of black people just as I love his exaggerations of country folk and and prissy clergy.

As for the economic question, doesn't that become kind of a cart and horse issue? If you can make more money by pandering to racism, don't you eventually become culpable after a while for reinforcing and prolonging it?

I'm glad you know the Mayer speech, not many people do.

Richard-- to show you how clueless I am, I didn't even realize there was a Cheerios commercial with a mixed marriage. Looking into it, I learn that there are now three prime time television romantic comedies with a blonde white woman married to a black man. I assume these trends don't take place on a whim, especially from the networks. Some marketing genius somewhere must have data to show that there is a nice couple of bucks to be made from the new demographic. If that's the case, it supports your theory that the market giveth and the market taketh away.

Would a reader of the great SEP really be put off from buying a copy because there was a black face in a crowd scene? I think the argument that "it wasn't really racism, it was just a commercial decision" would have to be one of the most mealy -mouthed excuses for racist attitudes I've heard.

Drew-- I think most of us have a hard time today comprehending the thought processes of virulent racists from the 1950s. If you look at the Norman Rockwell Museum site I referenced above, you'll see quotes from the angry letters Rockwell received when he painted a 6 year black girl (Ruby Bridges) being escorted into all white school by federal marshals:

“Anybody who advocates, aids or abets the vicious crime of racial integration is nothing short of a traitor to the white race.”

“It is nothing short of a heinous crime to mix little white and black children and brainwash them with the infamous lie that the only difference between the white and black races, is the color of skin.”

“THERE CAN BE, AND THERE WILL BE, NO COMPROMISE WITH THE VICIOUS CRIME OF RACE MIXING AND INTERGRATION. THE WAR HAS JUST BEGUN!”

These sound to me like the kind of readers who would refuse to buy a magazine with a black person sitting amongst whites on the cover.

I can see how an editor who was trying to produce a "least objectionable" magazine for maximum circulation to every part of the country might be scared away from illustrations that could trigger such mail.

There was certainly an economic cost to Briggs from destroying his cover painting; he might easily have said, "I have my own enlightened views about negroes, but they are separate from the purely economic actions I take to feed my family." One of the reasons we are saluting Briggs today is because he didn't do that.

Briggs has only gone up in my estimation as has Rockwell.

Back in the late 50s early 60s we had a lot of U.S black musicians touring the UK, playing shows side by side with white performers and staying in the same hotels and guest houses, to a man they were astonished to be treated like equals, and from our end astonished to find that in their own country they didn't even have that status. I believe this welcoming response was found throughout Europe and Scandinavia, so it's a bit difficult to relate to the depth of hatred you describe.

Drew,

Your pristine moral clarity has really shown me the error of my ways. From now on, I will do everything in my power to get Ben Hibbs fired from the Post in 1950.

Also, congratulations on Europe.

If only the problem had been confined to one editor on one magazine.

I suppose flippancy is one way of addressing the issue.

Another method would be a time machine.

If only your brain didn't automatically dispense you a little chemical treat every time you successfully deployed evidence of your moral superiority into the conversation.

As for the economic question, doesn't that become kind of a cart and horse issue? If you can make more money by pandering to racism, don't you eventually become culpable after a while for reinforcing and prolonging it?

I’ll leave aside the loaded phrase “pandering to racism” in reference to the story at hand... especially given that, the world over, people prefer and feel most comfortable around images of people who look most like themselves...

Does seeing rows and rows of delicious sugary cakes and snacks for sale in your local grocery store challenge your ability to agent your own health? Or do those items, the very presence of them, encourage a sense in you of permission, that now you are exempt from personal responsibility and consequences and may eat as you please?

Another way of putting this is that if the people are humane, the products offered to them will be also, because the inhumane producers will go out of business for want of demand.

As an alternate to “good speech drives out bad speech,” I would say a good sound moral mind is impervious to the suggestions of bigots. If we rely on companies and the media to give us our morals, that is only slightly more foolish than getting them from demagogues. All to say, I am against Maoism in all forms. Not least because it makes for bad art that divides around tribal/political issues instead of uniting around shared truths and humanity. As an alternate to maoism, I propose good parenting.

Back to leyendecker for a sec: That Carter article made the point that most black people in the south at that time were dirt poor. That these conditions were almost entirely caused by society around them did not alter that fact. Thus, when Leyendecker painted that Mother cooking a turkey for her young son in a run down ramshackle kitchen, he was making an image of a commonly held fact of the time. That you instantly labelled that mother figure a “mammy” was much more offensive to me than the content of the picture.

It so happens that I’ve met that woman before in my life on several occasions. On one such occasion, at a college some years ago, I came face to face with the splitting image of one of leyendecker’s caricatures of that type of woman. The woman was mopping a floor in one of the school buildings, and she was wearing every bit of clothing that Leyendecker depicted in his pictures, including the kerchief around the head in just that style. I thought I had walked into an alternate reality. But I hadn’t. This was a real person, completely unconscious that she was an offensive stereotype in the eyes of the sophisticated. It turned out that she was from Jamaica, as it happens, but that did not alter the facts of her appearance. If she wasn’t offended by the way she looked, why should I be? I imagine such big strong dutiful women graced a great many pot bellied stoves in American in Leyendecker’s time.

This is of a piece with the argument I have with people who say that Rockwell lived in a dreamworld. When, as I’ve said on this blog a few times, I’ve met many of the types of people Rockwell depicted. Same as A.B. Frost.

I worry that most people’s imaginations are so confined to their own social perspectives, that when they look back in the past all they can see is what they are spring-loaded to find offensive.

Drew, of course black-skinned musicians were treated more respectfully in GB than in the US.

There are so many reasons for that it's hard to know where to begin.

Let's see... most obviously, there simply weren't enough black people in the UK for any hard feelings to grow. Even today, the UK is ~92% white. ~2.5% black. In the UK in the 1950s, the percentage of non-White citizens was half that. Compare that with the US, where in the South today, blacks are generally about 30% of the racial makeup, and those numbers were even higher in the 1950s. They were also flooding into northern industrial cities at what must have been alarming numbers. It's really easy to say "Look how not racist we are!" when you're not actually having to deal with the realities of race relations, which brings me to...

White Americans, especially in the south and in the major cities, saw blacks "taking our jobs". The influence of a quickly rising black population on the labor market was immense. This was the primary reason for the passing of the incredibly-racist Davis-Bacon act of 1931 (which created the first minimum wage laws), despite what liberals today will claim. The law required businesses to pay the "going wage", which was essentially the union wage, a wage much higher than any non-union black laborer was receiving at the time. Even today this law keeps a large portion of the Hispanic population out of work.

Prior to the passing of the Davis-Bacon act, black unemployment was at its lowest in American history, while even today blacks have a higher unemployment rate than they did right before the passage of the minimum wage laws. They were educating themselves in record numbers, and were willing to perform jobs for a percentage of the pay of white Americans. In the words of Mississippi representative John Cochran in the primary debate about the DB act, “[I've] received numerous complaints in recent months about Southern contractors employing low-paid colored mechanics.” Congressman Upshaw said, in support of the bill, "You will not think that a southern man is more than human if he smiles over the fact of your reaction to that real problem you are confronted with in any community with a superabundance or large aggregation of negro labor."

By the time the 1950s had rolled around inflation had mostly eaten up the barriers to entry that the minimum wage laws had created, so once again there was an enormous influx of black labor into jobs whites had felt previously secure in.

Next, being primarily the offspring of the offspring of slaves, American blacks were by-and-large poor, with all of the social problems of poverty (e.g large amounts of alcoholism). To a population only beginning to be educated in genetics, it was easy to jump to the faulty conclusion that this was hereditary, and the common belief was that genetics would show that to be true soon if it hadn't already. By contrast, most blacks in the UK were recent immigrants which means they were self-selected to be middle class, with some education, the sort of people who would pack up and emigrate half-way around the globe.

Finally, because the black population in the US was large, its mobilization politically was very visible, which at the time seemed an immense threat to the way of life of white Americans. This was not only an American fear. In 1968, in the UK, the Gallup organization reported that 70% of British citizens agreed with Enoch Powell that, "In [the UK] in 15 or 20 years' time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man." The difference being that in the UK they saw it as same way off, in the US it seemed to be around the corner in the south.

Kev says "Thus, when Leyendecker painted that Mother cooking a turkey for her young son in a run down ramshackle kitchen, he was making an image of a commonly held fact of the time."

And if artist was a subcategory of journalist that might be the end of the story. Of course, an artist's job is more often to show what should or could be, not to merely show what is.

When what is the fact of the time is a great injustice, to paint beautifully that which is the fact of the time, rather than to subvert it, is itself a sort of acceptance of that great injustice.

The moral obligation of the artist lies in a higher truth, their brush should in some way distantly outline their vision of Utopia, or to show what is Dystopian in the here and now.

Lots of good stuff in your responses, Richard. I'll just tackle your last post, where we most disagree.

Firstly, nothing is off limits to the artist. You should watch that tendency to want to limit expression.

You should also watch the tendency to only view people according to the cause you attach them to, as if they were only pawns in some grand political or socio-economic game. Which is to say, when people are impoverished due to circumstances beyond their control, for instance, their impoverishment does not wholly define them. They are still human beings with beating hearts, lives, traditions, and work to do! All of which is fit for art.

Secondly, the moral obligation of the artist is his own business. The artist does not need you to tend their moral garden for them. Tend your own garden.

Thirdly, your belief that higher truth is necessarily utopian or necessarily the presentation of a current injustice, is myopic in the extreme and flies against most philosophical traditions as to what constitutes truth.

To wit: Truth is anything that is true. Any general idea that connects up and makes sense of otherwise disparate facts. Not just the current injustice du jour. An utopian vision might be a "higher" vision, but like most fantasies it has nothing, necessarily, to do with truth.

Also, squalor may be portrayed factually without actually creating a decent work of art. What of quality in your formulations?

If you want to live in a Maoist society, where all communications must be "on message" politically according to the presiding moral authorities, you might try North Korea or Saudia Arabia. Just because you consider yourself a moral person, does not make you any less imperious while seeking to control communication between otherwise free citizens.

I'll try to reply soon, but my newborn is taking up my time.

Would love to hear what David has to say.

As an aside, David, can you point me in a good direction for an illustration community in DC? I've hit up Richard Thompson and Mike Rhode since I moved here, but they seem to be too busy to communicate with me. Any younger communities? Is SPXPO my best bet?

With present hindsight hateful but at the time understandable: The wholesome image of America held by white Americans in, say, April, 1950, did not include black people sitting amongst them. No, not even in Harlem or Chicago jazz clubs. Jackie Robinson (voted National League Most Valuable Player in October 1949), Joe Lewis and others were admired but... no, not part of the white set.

Richard. i think you make some good points, and it most certainly would not be true to say that immigrants of any stripe didn't come up against pockets of discrimination. there was a famous sign on many an inner-city boarding house,

"No Blacks, No Irish, no Dogs"

Where you are wrong, in absolute terms, is the description of Jamaican/West Indian immigrants that arrived after WW2.

Far from being middle class, they were mostly poor working class -unemployed- folk who were shipped over to the UK on a promise of emplyment to work on the buses, in factories etc to fill the gap created by the huge loss of life during the war. Their transport costs were paid by the UK government and transported here on the famous HMS Windrush (the so called Windrush Generation).Finding Britain colder and greyer than they'd been told, many wanted to go straight back home.But the process of mass integration started at that stage and mostly went well.

There were definitely no suggestions of racial inferiority or racially motivated lynchings etc.You should also remember that British society had a lot of immigration from India and the sub-continent to contend with.

While I would never presume to know more about the U.S than an American, you're knowledge of the settlement patterns of UK immigrants is faulty.American musicians were playing shows in the major cities which is where they were staying, which is also where Blacks and Indians were settling to work, so the suggestion that these Black musicians were were some rare exotic species is totally inaccurate.

Drew:

The black musicians visiting the UK in the 50s were largely part of an exchange programme devised by the showbiz unions of the time. They were mostly jazz musicians, and the host country was receiving the cream of the talent performing a music invented in America in exchange for Britain’s home grown imitators. The UK club owners, audience and musical community were in utter awe of them, and treated them with the respect that was their due. A fact endorsed by contemporary statements from the visiting black musicians themselves. But idolatry was not the entire reason. More importantly and more significantly, these circumstances ensured they mostly received the hospitality of a broad minded, educated and sensitive demographic within the UK populace. In addition, it was from those who belonged to a cultural minority, empathic to the broader and more serious plight of their visitors from the US.

Drew-- I agree that both Briggs and Rockwell deserve credit for the positions they took. Your point about black musicians is compatible with much that I have learned about the arts in that era. Illustrator Bernie Fuchs grew up in a segregated town in the 1950s, but as a boy snuck away to an all black nightclub to watch the musicians play the jazz he loved. Fuchs himself became a professional jazz trumpeter in high school, and used to jam on stage with the black musicians. (At one point a customer at the club, resentful of the white boy in an all black club, pulled a large knife on Fuchs, but his band mates rescued him and once the customer heard how Fuchs could play, he said "OK, you can stay.") Music expanded Fuchs' understanding of race relations and helped him to throw off the shackles that his racist grandfather had imposed.

Kev Ferrara wrote: "If we rely on companies and the media to give us our morals, that is only slightly more foolish than getting them from demagogues."

I think the issue is a little more slippery than that. The US Army became a great force for integration in this country because the President ordered that white recruits, who never lived side by side with blacks or got to know them, integrate with them in the armed forces. They returned to their all white communities with a broader understanding . Similarly, when the SEP deliberately avoided covers where whites might see blacks participating in the same kind of normal, everyday activities that whites did, they made it easier for some whites to dehumanize blacks. That's something less than "the media giving us our morals," but in my opinion it is still pernicious.

PS-- I think the term for the woman in the Leyendecker cover is indeed, a "mammy" figure. You can look it up on wikipedia (under "mammy archetype") or google a thousand "mammy" images or read a dozen black history texts. The term is not meant to be pejorative at all (you may be thinking of Al Jolson), it's just the term currently being used, as far as I can tell. Do you know a substitute term?

Richard-- Well bless my soul, I never thought I'd be discussing the Davis-Bacon legislative history on this blog, but it happens to be something I know something about, as I have counseled a number of clients on it and handled more than one case involving the complexities of the law. During our lifetime, I would say that the David-Bacon law is pretty well recognized as a pro-union, and not an anti-black, law, devised to maintain minimum wages and prevent the government from saving money by contracting for sweat shop labor (just as the Walsh-Healey Act and the Service Contract Act try to promote labor conditions in federal contracts for goods and services). It is possible that at its origin the D-B act had racial consequences, although people were so concerned about jobs and wages during the depression when the law was enacted that harming blacks may have been a side benefit rather than the central thrust of the law. Anyway, an interesting take on things. There's no denying that economic fear plays a large role in the feelings we're discussing.

If you've recently come to Washington DC, welcome. I wish I knew the illustration community in DC, but I spend all my time with the corporate legal community. (If you know about the D-B Act, perhaps you'd care to meet them instead?) I know a number of individual artists scattered around the country, but I'm really pretty much a full time lawyer in DC. The small press expo is definitely a good place to start. Write me at David.Apatoff@gmail.com and I'll see what I can do.

The US Army became a great force for integration in this country because the President ordered that white recruits, who never lived side by side with blacks or got to know them, integrate with them in the armed forces. They returned to their all white communities with a broader understanding .

This is a different point entirely. Every public space, institution or entity in the United States is subject to the nation's laws against discrimination or "separate but equal" type crypto-racism. Integrating the armed forces was simply following the letter of the law. Same with integrating the schools. Same with allowing African Americans or any other minority to buy property and go to school anywhere they so choose without fear of violence or bullying or racial hectoring, etc.

Love that Epicetus quote. So true. Thanks, David.

"The Saturday Evening Post would not have to ask Briggs to paint out the African American woman; they would Photoshop a white complexion on her without the artist's permission in 30 seconds."

Would it be pedantic of me to point out that this wouldn't actually be possible? You'd still have to repaint her skin, at the very least; the value relationships in African skin compared to Caucasian skin would be too different for a hue shift to make her look Caucasian. And if Briggs drew her competently (har har), just changing her skin tone would only make her look like an albino Black woman; her facial features at least would probably still be distinctly African.

Photoshop is amazing, but it has its limits. I probably am being pedantic, but as someone who uses Photoshop all day, my ego is threatened by the idea that it's that easy to make so major a revision as changing a figure's ethnicity.

Anyway, great post as usual.

Post a Comment