|

| Brunetti |

|

| Ware |

|

| Gauld |

|

| Niemi |

|

| Ware |

|

| Brunetti |

The Ebola epidemic was centered in West Africa, while the circle head epidemic seems to be centered at The New Yorker magazine, which apparently finds this style charming:

Fortunately, some parts of the art world appear immune to the virus. Ivan Brunetti applied for the job of artist on the simple minded comic strip Nancy but did not draw well enough, so he had to become a New Yorker cover artist instead.

Doctors have discovered a clue to the origins of this epidemic in the excellent reference work, Graphic Style by Steven Heller and Seymour Chwast. The authors write that a style called "information graphics" was developed by artists such as Nigel Holmes in order to present simplified information to popular audiences.

|

| Holmes |

The authors described the information graphics style as:

graphic design working toward the goal of clarifying simple and complex data. The key difference between information design and general graphic design is transparency. Ornament and decoration are unacceptable if they hinder perception. Information graphics have, by virtue of a common visual language, become a sort of style.Information graphics began as a method for "quantitative visualization," useful for conveying information but lacking the sensitivity, complexity or range necessary to convey weighty ideas. Yet today this style has become a popular vehicle for weighty ideas such as social commentary or "deep" emotions. Why?

|

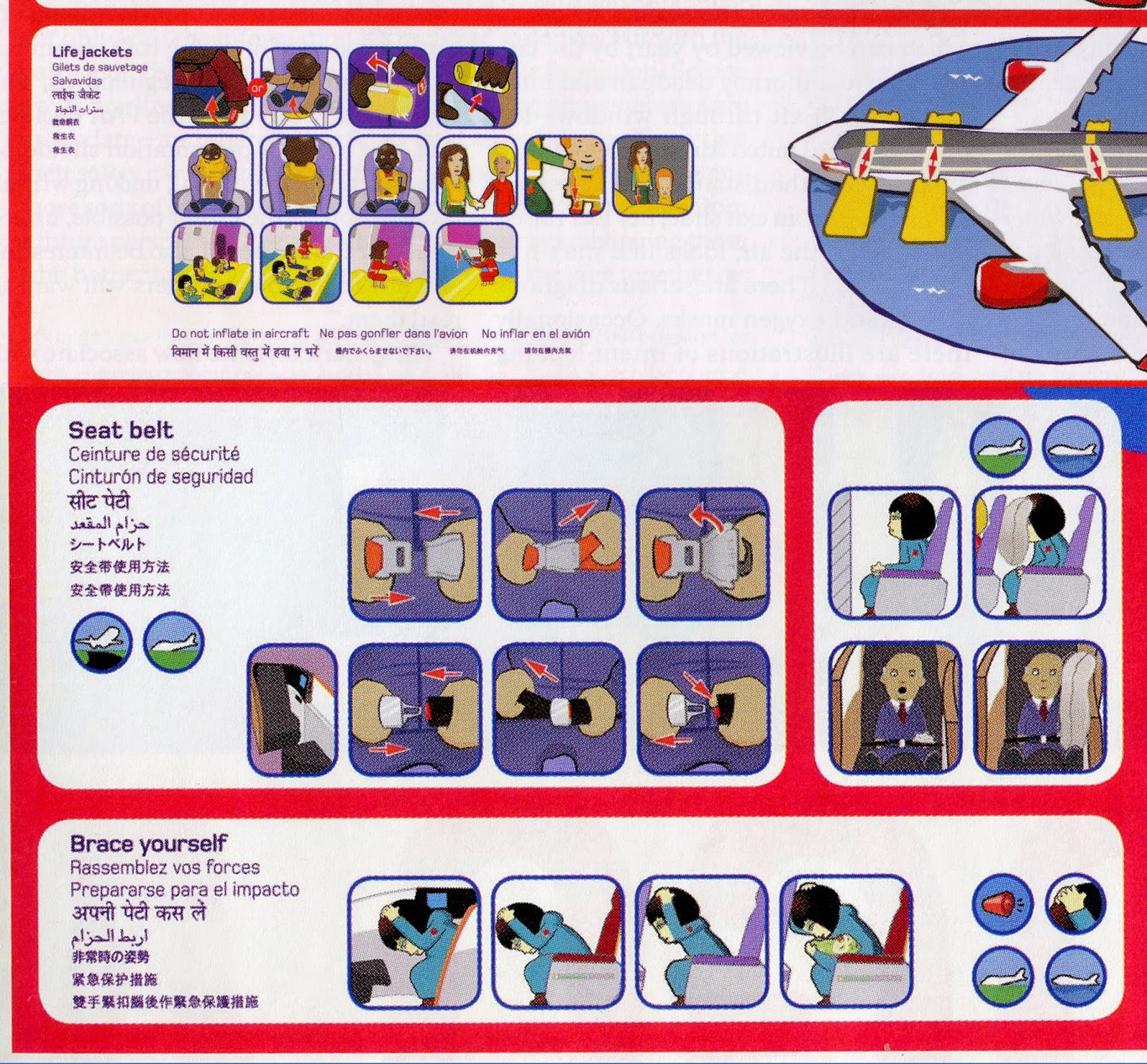

| Is this the latest dazzling display of genius by Chris Ware? No, it's from an airline information card created by some underpaid staff artist. |

For starters, cultural awards (and New Yorker covers) are often bestowed by people who specialize in concepts but seem to have little appreciation for the qualities of line, color or design. (A good example would be the confused Dave Eggers, who embarrassed himself by asserting that "The most versatile and innovative artist the medium has ever known" is Chris Ware.)

But more importantly I suspect our ambitions for the graphic arts (and consequently our priorities and taste) may be evolving in the information age. The insightful Karrie Jacobs wrote,

Computers have seduced us into thinking about ideas--the intangible stuff that comprises our culture, our meta universe, our homegrown organic realities-- as information.The perfect visual style for such a society is "information graphics." The following drawing by Brunetti conveys the fact of sex, the information that the characters are engaging in sex, but conveys nothing worth knowing about the idea of sex.

This seems to be a weakness common to the circle head artists (as well as the artists who draw square heads with the same monotonous line, insisting that good draftsmanship would only impede the flow of their words.)

Visual art once prided itself in challenging our perceptions, but information graphics do the opposite: as Heller and Chwast note, information graphics aim to purge any details that might "hinder perception." If there is anything oblique or profound to communicate, it will be done with words.

So why does this epidemic of circle heads matter? The drawings above are pleasant enough to fill a blank space. Besides, travel agents and telephone booths were rendered obsolete by the information revolution, so why shouldn't the inefficiencies of art also be stripped away, so readers don't linger too long over the drawing in any one panel? What is lost if the efficient processing of information dumbs down our appreciation for visual form?

Here's my personal answer: It's great that images can be harnessed to convey information, such as the motion of a character opening a door. But art-- good art-- has the potential to do more, to provide us with subtler shades of meaning for communicating love and pain on levels where words are inadequate. It can strengthen our sense of aesthetic form that we rely upon to fend off entropy. It equips us with a vocabulary for fleshing out profound concepts of joy or sadness or humor or introspection.

Art enables us to express a range of moods, feelings and beliefs that are more important than mere information and that cannot be conveyed well with information graphics-- even in an era when such graphics are the literati's vision of "art."