|

| Brunetti |

|

| Ware |

|

| Gauld |

|

| Niemi |

|

| Ware |

|

| Brunetti |

The Ebola epidemic was centered in West Africa, while the circle head epidemic seems to be centered at The New Yorker magazine, which apparently finds this style charming:

Fortunately, some parts of the art world appear immune to the virus. Ivan Brunetti applied for the job of artist on the simple minded comic strip Nancy but did not draw well enough, so he had to become a New Yorker cover artist instead.

Doctors have discovered a clue to the origins of this epidemic in the excellent reference work, Graphic Style by Steven Heller and Seymour Chwast. The authors write that a style called "information graphics" was developed by artists such as Nigel Holmes in order to present simplified information to popular audiences.

|

| Holmes |

The authors described the information graphics style as:

graphic design working toward the goal of clarifying simple and complex data. The key difference between information design and general graphic design is transparency. Ornament and decoration are unacceptable if they hinder perception. Information graphics have, by virtue of a common visual language, become a sort of style.Information graphics began as a method for "quantitative visualization," useful for conveying information but lacking the sensitivity, complexity or range necessary to convey weighty ideas. Yet today this style has become a popular vehicle for weighty ideas such as social commentary or "deep" emotions. Why?

|

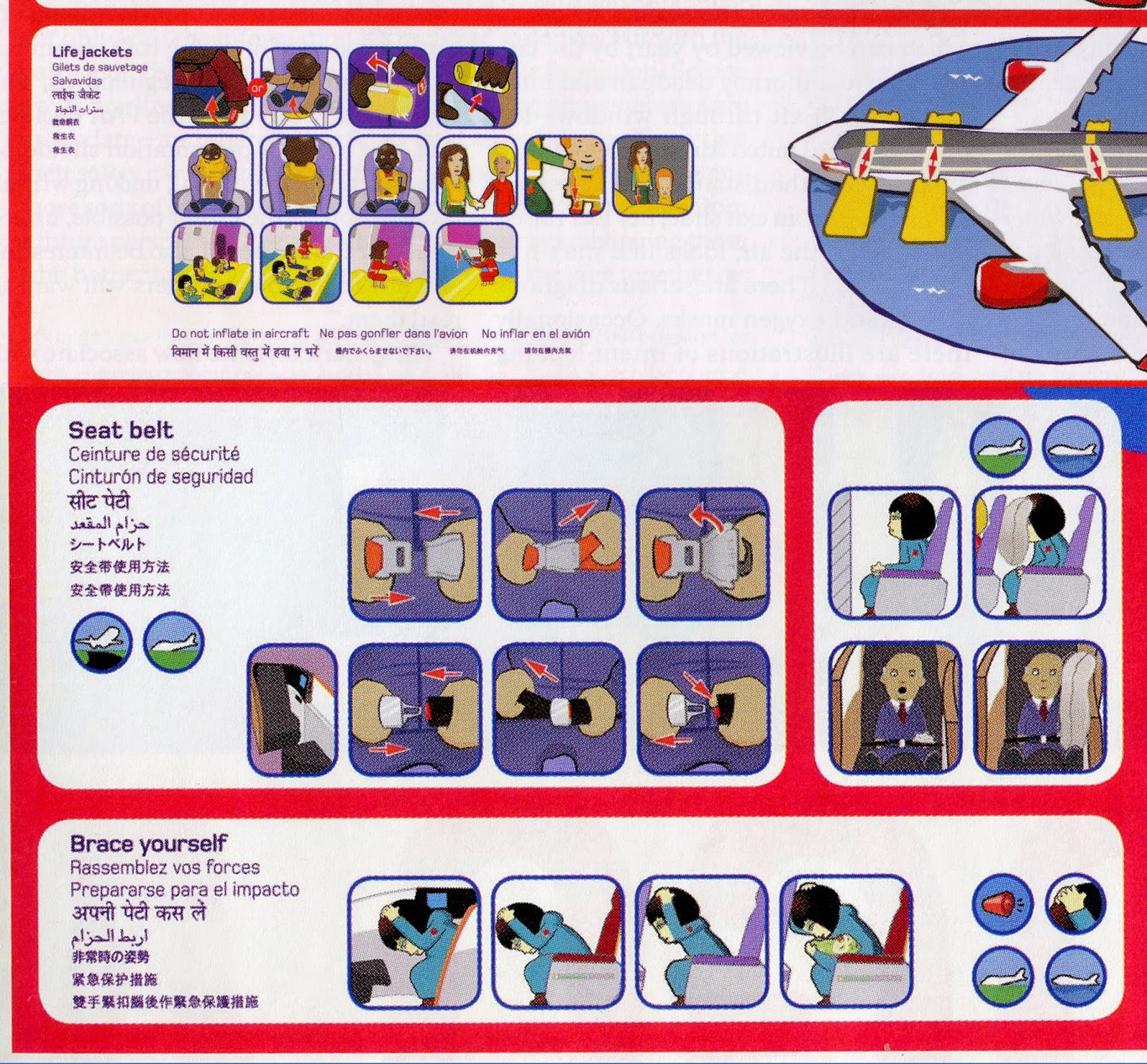

| Is this the latest dazzling display of genius by Chris Ware? No, it's from an airline information card created by some underpaid staff artist. |

For starters, cultural awards (and New Yorker covers) are often bestowed by people who specialize in concepts but seem to have little appreciation for the qualities of line, color or design. (A good example would be the confused Dave Eggers, who embarrassed himself by asserting that "The most versatile and innovative artist the medium has ever known" is Chris Ware.)

But more importantly I suspect our ambitions for the graphic arts (and consequently our priorities and taste) may be evolving in the information age. The insightful Karrie Jacobs wrote,

Computers have seduced us into thinking about ideas--the intangible stuff that comprises our culture, our meta universe, our homegrown organic realities-- as information.The perfect visual style for such a society is "information graphics." The following drawing by Brunetti conveys the fact of sex, the information that the characters are engaging in sex, but conveys nothing worth knowing about the idea of sex.

This seems to be a weakness common to the circle head artists (as well as the artists who draw square heads with the same monotonous line, insisting that good draftsmanship would only impede the flow of their words.)

Visual art once prided itself in challenging our perceptions, but information graphics do the opposite: as Heller and Chwast note, information graphics aim to purge any details that might "hinder perception." If there is anything oblique or profound to communicate, it will be done with words.

So why does this epidemic of circle heads matter? The drawings above are pleasant enough to fill a blank space. Besides, travel agents and telephone booths were rendered obsolete by the information revolution, so why shouldn't the inefficiencies of art also be stripped away, so readers don't linger too long over the drawing in any one panel? What is lost if the efficient processing of information dumbs down our appreciation for visual form?

Here's my personal answer: It's great that images can be harnessed to convey information, such as the motion of a character opening a door. But art-- good art-- has the potential to do more, to provide us with subtler shades of meaning for communicating love and pain on levels where words are inadequate. It can strengthen our sense of aesthetic form that we rely upon to fend off entropy. It equips us with a vocabulary for fleshing out profound concepts of joy or sadness or humor or introspection.

Art enables us to express a range of moods, feelings and beliefs that are more important than mere information and that cannot be conveyed well with information graphics-- even in an era when such graphics are the literati's vision of "art."

59 comments:

Perhaps even more stripped down are "pictograms" that were often used in the 1930s to display data such as comparative sizes of armies of European nations or whatever. (Figures, each representing 50,000 men, say. So one country might have four such figures and another could have six and a half -- one pictograph soldier being cut in half vertically.)

I see that Wikipedia offers a broader, more generic context for the word. But Google Images shows a variety of examples including some similar to what I recall.

I think the worst aspect of this is homogenization. Once this style gained enough renown as in The New Yorker, young people who get influenced by this will just skip the actual drawing part of being an artist. It is already happening.

Thanks for the post David, it made me chuckle. I only disagree with you on definitions:

In my view, the panel of the copulating couple is conveying the idea of sex, not the fact of it. And further to this, I'd say all handmade images, from information graphics to paintings alike, do not convey facts either. The unadorned, un-Photoshopped, photograph is the nearest to a fact in that it evidences a consequence of the light falling on a particular instant in time recorded dispassionately with a machine. The handmade image is never this, it is always a fiction, always alluding to experience.

So as I see it, the information graphic, the cartoon, the sketch, the tonal drawing, the painting and the full-blown masterpiece, i.e. all handmade images, are conveying ideas. The difference is that the information graphic is a consensus idea, a ‘platonic’ statement of experience at one end of a visual language scale of increasing sensuous evocation.

i think 'transparency' is a very good description of how Ware's comic art works so effectively. the reader literally 'sees through' the infographic and fleshes it out with memories from their own experience which most closely resemble the signs.

(and, as i've quoted before): Ware himself admits that his work operates "somewhere between the worlds of words and pictures, sort of where road signs and people waving their arms in the middle of lakes operate" ... which is a frank admission that this is not a purely visual language. it is part literary.

Well now... this looks like a nice pool to cannonball into...

Ahem. (clears throat)

First, some foundation, the givens. Text is docile, anaesthetic and surfaced as a medium of information transfer. Words are all ready-mades, previously defined both in look, in meaning, and often even in point size for presentation. While Art is forceful, sensual, mysterious, and uncodified by nature. (This is regardless of the content, I'm speaking solely of the medium itself, used with competence.)

I know quite a few bookish people who simply can't tolerate the stimulus of powerful, sensual, and mysterious art, where there is no dictionary to look up what is being ingested through the eyes. (I think this population is rising steadily, and has been for some time, as population density and various ideological madnesses wall everybody in to their study rooms.)

I have always wondered if there is some kind of spectrum-disorder issue at root there. Or whether there is simply a natural oversensitivity to aestheticized information that leads bookish people to retreat into bookishness.

Or whether bookishness as a life-habit is so anaesthetic and protected that it actually leads, in some or many, to one's normal childhood oversensitivity to forceful stimulus continuing on into adulthood. In other words, the root issue is inexperience, and how that retards psycho-aesthetic or psycho-emotional maturity.

Either way, there seems to be a correlation between bookishness, existential anxiety, and a preference for anaesthetic graphics and art. In other words, text-people want information graphics to be their illustration (and fine art) because they psychically can't handle anything more.

I think their intuitive need to shield their oversensitivity, added to the bookish word-centricity, leads to any number of nonsensical, pseudo-intellectual rationales for why powerful art isn't any good; why real art must be circles for heads and red squares on white canvas or my politics which I've read up on, and not theirs. (The ego that attends verbal and textual articulateness will never allow the idea that there is inexperience and frailty at play in their preferences.)

What this anti-romantic push really amounts to is a need to control stimuli; to control the force of cultural products, in order to keep ambient anxiety under control. And a control freak is always going to hate when they can't understand what is being said in any particular room they might find themselves in.

The mass rise in bookishness, to me, is an important predicate for Thomas Wolfe's Painted Word thesis.

That bookish, artistically incapable, psychically-fragile people have long since taken control of critical discourse on painting is exactly how and why it has been eradicated from high culture in its strongest form. And we are left with aesthetically denuded graphics of various types all across the board, from The New Yorker's robotic-infantile egg-head graphics, to Murakami, to Miro, to all white canvases, red squares, etc.

This is very funny and I agree with all the comments.

Kev,

the New Yorker has printed covers by Carter Goodrich and John Cuneo in recent years, both artists who have been celebrated many times on this blog. they might not quite be the "forceful, sensual and mysterious" art you refer to, but to suggest that all the New Yorker offers is "robotic-infantile egg-head graphics" would be incorrect.

I agree with you Laurence, of course. I didn't mean that everything was robotic-infantile egg-head graphics. My main point was that this push toward intellectualized graphic reductionism is a long term trend in all the visual arts that seems tied up with a mass rise in nerdiness, geekiness, dweebitude, and bookishness. It was a sociological observation, not an indictment of the New Yorker as a whole.

Kev,

it doesn't say much for the power of the art in question if it can be eradicated by a couple of generations of dweebs.

would that really be possible unless something else was afoot ?

( i'm thinking of painting and illustration's waining importance in the average person's life with the rise of photography, cinema, and TV ).

i remain skeptical, but i hope you will write a thesis on this topic one day where you can go into greater depth on your theories.

Good thoughts, Kev.

Donald Pittenger-- I think that comparing the sizes of armies of European nations is an ideal use for these kinds of "pictograms." I'm just not sure they're the best medium for conveying the urban despair that eats away at the souls of humanity.

Gennaro-- I agree that if young people become convinced they don't need to draw in order to become an artist, more and more of the wrong types of talent will scramble onto the life raft.

Chris Bennett-- When you say the copulating couple conveys the idea of sex, how would you describe that idea (other than the empirical fact that it is taking place)? I wrote that the picture "conveys nothing worth knowing about the idea of sex," because I felt it conveyed nothing about the emotions, feelings, or anything else interesting about the relationship between the couple. It also conveyed nothing about the physical experience of their muscles or nerve endings, nothing about the heat or other sensations. We can tell that she is being entered from behind, but that's about it.

When you say that "the information graphic is a consensus idea, a ‘platonic’ statement of experience at one end of a visual language scale of increasing sensuous evocation," I assume you aren't referring to your progression from "the information graphic, the cartoon, the sketch, the tonal drawing, the painting and the full-blown masterpiece," because I think the slightest sketch can be a very "sensuous evocation." Klimt, Schiele and Rodin showed that you don't need details or colors, that a few expressive pencil lines can be quite steamy if you have talent.

I would agree with your notion that "the information graphic is a consensus idea" but in these instances that doesn't make it a Platonic ideal, that makes it the lowest common denominator.

Laurence John-- I swear I'm not trying to be unduly harsh on these artists, but it seems to me that a more effective way to invite viewers to "flesh out a picture with memories from their own experience" would be to "imply" the scene with loose, economical gestures. (For example, Henry Raleigh used to scribble backgrounds with a lightness that enabled the reader to climb right into the picture with him and fill in all the gaps: Is that a grand ballroom in the background? I'll bet I know what that chandelier looks like. And that drapery on the pillar is probably red velvet.) Ware's pictures, on the other hand, employ a different kind of economy. They are stripped of detail but are constructed as tightly as an interlocking jigsaw puzzle with all of the pieces accounted for. For me, that makes them seem closed to any kind of covalent bonding with the viewer. Other people may react differently.

I do agree with you (and Ware) that his work is partly (or even mainly) literary which could explain its appeal to a literary audience. The words do the real heavy lifting here because-- in my opinion-- he doesn't draw well enough to employ images the way a stronger artist would.

MORAN-- Well, that's a first.

Laurence, I absolutely agree with all those factors you mention as part of the issue. There are quite a few other factors as well that were not at all necessarily fated to be, some in the realm of "sharp practice" as it were. But I would point out that this is what I wrote:

"That bookish, artistically incapable, psychically-fragile people have long since taken control of critical discourse on painting is exactly how and why it has been eradicated from high culture in its strongest form."

Note that I was specifying "high culture"... the realm where intellectual infantilism has reigned unchallenged. The New Yorker set is part of that mileu, a barnacle on the rowboat, so sad is the current state of things. (See Andy Borowitz for how intellectual infantilism looks in the print.) But it would also include everyone from ambition-where-his-brains-should-be Jerry Salz, to the hypocrites at the NY Times (who will hire Dan Adel to paint a cover for their sunday magazine, but won't review his fine art shows at the Arcadia gallery), to the Arthur Dantos of the world (who spin elaborate apologetics for crumped-garbage-on-a-table kinds of art installation pieces), to all the pomo "art teachers" installed in academic strongholds I hear about who spend class time ranting at projected images of 19th century painters ("This is not art! This is garbage! If you ever dare to do work like this, you might as well leave my class right now!")

In the long term, in the short term, in any term, really, great art needs great patrons. Great art is hard damn work physically, emotionally, intellectually, spiritually. And no artist can long sustain quality work without compensation for his efforts and a supportive culture around him. And sometimes, when the market going gets tough, it is left to institutions alone to support a truly fine art... to provide that culture. But the institutions that would have provided that support to the visual arts had already been taken over by the intellectual infants who were dead set on severing cultural ties with opposing aesthetic ideas.

David,

if i had to make a short video explaining how the simplified-symbol-world of Ware and others works it would look like this:

-shot of reader looking at a comic book.

-shot of the comic panel: a circle-headed old man with sad mouth and a tear falling from his head.

-shot of reader looking puzzled / intrigued.

-shot of a photo of the readers actual father, in a similar pose to the cartoon, looking sad. the photo match-dissolves back to the cartoon drawing of the circle-headed old man.

-shot of the reader again, this time visibly moved.

Kev Ferrara-- I would not be quite as tough on words as you are. After all, words can also set hearts ablaze. General Washington had Tom Paine's words (“These are the times that try men’s souls...") read to the troops to motivate them before crossing the Delaware, and it worked.

But I do agree that images are potentislly a more radical and anarchistic and scary medium than words, and that there is a bookish sect within the current governing culturati that does not seem to understand or give images their due. This makes things especially awkward when words and pictures are blended in newly legitimate graphic novels and in cartoons (gasp) in the New York Times. Writers feel compelled to speak out about the pictures and end up saying silly things such as the Dave Eggers quote in my post.

As we have discussed on this blog before, once lines have been civilized into letters and words, they can never return to their original pagan state. Language is rule defined, so it becomes unintelligible as it approaches chaos. But the lovely, wild line of art is still at home in chaos. That makes pictures harder to manage with office software, harder to categorize for google searches, or harder to classify for peddling stock illustration.

Laurence John and Kev Ferrara-- I too agree with Laurence about Goodrich and Cuneo. They along with Drooker, de Seve and a few others are top notch and do the tradition of Steinberg, Thurber and Steig proud.

p.s.

David,

you're right that the cartoon of the couple engaged in sex shows 'nothing worth knowing about the idea of sex'

and Chris is also right when he says that the drawing only shows 'the idea of sex'

it functions the same way that a symbol of a man on the men's room door functions: you recognise the basic graphic message, but beyond that, you have to overlay your own mind's eye imagery.

for instance, if you happened to have a shaved head, and your girlfriend happened to have a black bob, you might very well think "hey this looks like us having sex !" which of course it doesn't - literally - but does symbolically.

Raleigh, Klimt and Schiele do drawings that leave large areas of space undescribed, vaguely suggestive, implied... sure.

but they're also very specific about what they do show. so they function less as graphic symbols and more as specific likenesses.

they're about midway on the spectrum (with smiley-symbol-face at one end and photo-realistic at the other).

Laurence John wrote: would that really be possible unless something else was afoot ?

( i'm thinking of painting and illustration's waining importance in the average person's life with the rise of photography, cinema, and TV ).

I agree that there are many moving parts here (as does Kev, from his answer). It is occasionally emotionally satisfying to flog the corrupting influence of money on the fine art market (which certainly satisfies Kev's specification of "high culture") or the increasing ossification of an aging culture, or just the human nature that causes people to act in insufferably elitist ways. But I think the factors that you mention (photography and TV and--I'm assuming-- computer videos) are far more relevant. I think they have utterly transformed art, both high and low. That's not the result of lazy or bad people, that's the result of scientific progress.

Ales-- Well, he sure doesn't pull any punches, I'll say that.

Laurence John wrote: "it functions the same way that a symbol of a man on the men's room door functions: you recognise the basic graphic message, but beyond that, you have to overlay your own mind's eye imagery."

Well, if that's the sum total of the idea of sex being contributed, one has to ask, "why bother with a visual medium?" What does it do for you, besides attract readers who are insufficiently literate to read a whole book of words and therefore can use accompanying pictures to serve as a crutch?

After all, words can also set hearts ablaze. General Washington had Tom Paine's words (“These are the times that try men’s souls...") read to the troops to motivate them before crossing the Delaware, and it worked.

Agreed. But I wasn't speaking of content. Only medium.

That circle head couple is not even connected.

Here is weighty circle design, actually sphere design

http://kunstler.com/featured-eyesore-of-the-month/

It's everywhere David.

David: "Well, if that's the sum total of the idea of sex being contributed, one has to ask, "why bother with a visual medium?"

the speed of communication is why to bother. simple cartoons can express complex and / or funny ideas very quickly and effectively. they can illustrate a concept that might take a paragraph of boring looking text to explain.

they can also make a complex visual idea instantly graspable which would be bogged down with more and more realism.

look at how much information is relayed in the New Yorker cover with the people in the park doing various things. imagine how difficult it would be to make that image work in a realistic oil painting style !

Laurence

I agree with you, that a lot of complex information can be presented using simple shapes. But I still had to read the Ware covers for them to make any sense of them. And it took me quite while to understand that New year cover was a new year cover. The airplane information makes feel like I am still reading not looking.

My take on it is, the circle head does not appeal to the senses.

Unlike reading a painting or drawing can whole my attention in just how it looks, it holds me because it's beautiful.

i actually think there's something worth celebrating in these modern geometric hieroglyphics.

look at the first image of 'Tommy Trainer'.

really, it's a miracle we recognise anything in that image at all, since it's so abstract and un-life-like.

yet, it's a testament to the anthropomorphic power of the human imagination that we not only see what the image represents, but can understand its idea.

and - if we know someone who looks vaguely like that - we'll see him in the image too !

I agree with you Laurence that there is something fundamentally important here. Information graphics have become an essential visual language in their own right that have greatly aided understanding in many different fields of interest. From logic diagrams and electronic schematics, to pie charts and instruction manuals, to editorial illustrations and various sorts of signage.

However, diagrammatic visuals are a miniscule use of Art's capabilities to produce understanding and comprehension through the medium of visual fiction. Which leads to a strange paradox, that even though the visual fictions here have been reduced to barely anything, they still are difficult to process. One has to read them quite slowly, actually, in order to decrypt what is being indicated.

And this is because those other aspects of art that are being elided by the robotic-infantile style (mimesis, expressivity) are naturally-parallel methods of bringing visual understanding to the human mind (that usually work in tandem with diagramatic.) Another way to put it is that 2/3 of what has been cleared away here are other methods of visual signification. So what we are left with is mental clarity for people who only have 1/3 of their brains available to receive visual information. All to say, there are actually less opportunities here for understanding, for comprehension, and for clarity, not more. So even the functionality of diagramming isn't really being met.

So even though everything looks so clear in these pictures, the robotic-infantile style actually isn't bringing all that much clarity to bear. What it is bringing, I think, is comfort to those who spend their lives immersed in text. The open shapes, simple colors, and perfectly round heads of the robotic-infantile style probably function more as eye relief than anything else for those who are constantly straining to decode page-long walls of 8 point serifed text.

David Apatoff – “When you say the copulating couple conveys the idea of sex, how would you describe that idea (other than the empirical fact that it is taking place)?”

It’s what Laurence said about the sign on lavatory doors: the idea of ‘male’ and female. The idea here is simply that they are in the act of procreation.

“I wrote that the picture "conveys nothing worth knowing about the idea of sex," because I felt it conveyed nothing about the emotions, feelings, or anything else interesting about the relationship between the couple. It also conveyed nothing about the physical experience of their muscles or nerve endings, nothing about the heat or other sensations.”

And I agree with that. The ‘idea’ in this panel’ is very basic, but that doesn’t stop it being an idea.

“When you say that "the information graphic is a consensus idea, a ‘platonic’ statement of experience at one end of a visual language scale of increasing sensuous evocation," I assume you aren't referring to your progression from "the information graphic, the cartoon, the sketch, the tonal drawing, the painting and the full-blown masterpiece," because I think the slightest sketch can be a very "sensuous evocation." Klimt, Schiele and Rodin showed that you don't need details or colors, that a few expressive pencil lines can be quite steamy if you have talent.”

Yes, that’s true. But that progressive list is to do with the size of the available vessels, pitches, platforms or stages on which the artist can perform his magic. So sure, a marvellous Klimt sketch on the back of an envelope can say far more, and ring far deeper than some huge brown monstrosity of ‘The Wreck of the Hesperus’ dutifully set down by some academic on the great wall behind the high table at Cambridge. But no Klimt drawing can go as far as his portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. The best charcoals of Sargent don’t deliver as much as his best watercolours, and the best of his watercolours, as utterly beguiling as they are, do not have quite the emotional depth of his best oils; The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, The Vickers Sisters or Carnation Lily Lily Rose.

Kev: "So even though everything looks so clear in these pictures, the robotic-infantile style actually isn't bringing all that much clarity to bear."

look at the sheer amount of info on the New yorker 'new year' cover; can you imagine any other way to convey that same amount of visual info clearly on an A4 page ?

Kev:"... diagrammatic visuals are a miniscule use of Art's capabilities to produce understanding and comprehension through the medium of visual fiction"

i think they're doing something quite different to dramatic narrative art, but which is still interesting in it's own way.

they're using elements of diagram, graphic design, decorative pattern, abstraction and cartooning to deliver information in a poster-like way. i think that's valid, even if it's not very deep.

here's a 87 year old example.

I agree with all that Laurence. But I would add that it isn't just that this kind of work is shallow. It is also decidedly immature while also emotionally vacant; there's a wan blankness where its young heart ought to be. Like a cute little grade school kid zonked out on an ADHD cocktail; I just find it pathetic.

Yet, as I probably already said last time Ware was discussed, I could definitely see how a certain brand of person can find this work quite in their emotional zone. I just hate to think that this emotional zone defines in some way the principal New Yorker demographic. Are all the physically robust, life-charged intellectuals dead?

What a great post David, your instincts are really on it. The comments are also fantastic. Info graphic is a great way to put it. I hope I'm not just reiterating what has been said.

The info graphics such as man and woman symbols at airports, serve a purpose and everyone has gotten used to them, but words are like them only under certain objective circumstances, such as studying medicine.

The info graphic is less than a word because it says nothing more than itself. My mother, daughters, wife, or an old flame are women and yes, the word woman can refer to all women, but none of these appear in my head as an info graphic or as the five letters which spell woman. I may never understand women, but thoughts of women almost always trigger some subjective image or feeling, often of a particular woman, while an info graphic clearly infers to some generic without subjective meaning.

Info graphics tell us what we are rather than giving us an opportunity to be or find ourselves in an image. Such is the problem with ideologies which renounce and pretend to transcend subjectivity while reveling in the elated notion of transcendence itself.

The info graphic is a concept of mass design, a tool of the masters of the universe who see in terms which non-designing people find instinctively repulsive. Whether we really exist or not in any important way is something many people now doubt as the result of a fascistic info graphic type academic environment which only allows us to agree with what we are told.

How can one verify themselves if subjectivity is renounced at the outset? We are a mystery because we exist in relationship towards things, but not in a vacuum. Developed pictures and writing allows our personal memories to be triggered as pictures and feelings. But the info graphic mindset lacks the subjectivity and empathy by which one's distinctive personal life participates or is verified.

An info graphic type image can be personalized and such may be cute, but it is still telling us what we are, rather than allowing us to participate in the image.

Tom wrote: "It's everywhere David."

That photo of the barriers is depressing. You'd think that, after the proposal left someone's drawing board, there were 50 stages of review where people could have said, "This is a really bad idea." From the committee who approved it to the taxpayers who funded it to the construction company who bid on the job to the guy who poured the concrete to the poor slob who had to install them, why didn't someone ask, "Are you nuts?"

Laurence John-- If you will stick with me on this-- and I truly hope you will-- I would like to push deeper on your point because your views are probably shared by the majority of modern literate fans in this field, and I have been unsuccessful in cracking the code.

When the new "The Best American Comics 2014" arrived, I looked forward to reading editor Scott McCloud's explanation of Ware et al. After all, McCloud normally loves to analyze the hell out of everything and I was a willing student. But all he offered was the same unhelpful babbling that seems to infect everyone around Ware: "On almost any critic's list of North American cartoonists, Chris Ware's name is bound to land at or near the top. I know he's atop mine.... Cartoonists joke about the 'Chris Ware effect.' No matter how puffed up we get, no matter how pleased we may be with ourselves from time to time, one look at the latest efforts from the House of Ware and we all slink off to our inky sunsets, under gloomy thought balloons reading: 'I suck.'" For those of us who don't yet see the magic, McCloud's kind of drool is unhelpful (and carefully spending time with Ware's contribution to the book didn't help). So I am back sincerely looking for a navigator here.

I wrote to you, "Well, if that's the sum total of the idea of sex being contributed [an identifying symbol such as a man on the men's room door] "why bother with a visual medium?"

You responded: "simple cartoons can express complex and / or funny ideas very quickly and effectively. they can illustrate a concept that might take a paragraph of boring looking text to explain. they can also make a complex visual idea instantly graspable which would be bogged down with more and more realism."

I agree that simple cartoons are capable of doing that (look at Saul Steinberg) But what is the "complex or funny idea" being illustrated by the men's room door sign? What is the "paragraph of text" necessary to describe what is happening in the Brunetti scene ("They copulated.") What is the "complex visual idea which is made instantly graspable" by Brunetti's "Tommy Trainer?" I need someone who understands this kind of material to hold still and, with an example of their own choosing, explain the complexity and humor to me, rather than skittering out of reach the way McCloud did.

I agree when you say, "really, it's a miracle we recognise anything in ["Tommy Trainer"] at all, since it's so abstract and un-life-like. yet, it's a testament to the anthropomorphic power of the human imagination." As a result, I am prepared to give kudos to the anthropomorphic power of the human imagination, but why am I giving kudos to Brunetti?

(to be continued)

Laurence John (continued)-- You asked Kev if he could think of any other way to deliver the "sheer amount of info on the New yorker 'new year' cover." My quick and easy answer would be: Gluyas Williams, who specialized in simplifying his characters down to the most basic geometric forms for huge complex crowd scenes but also knew how to draw and had a marvelous sense of design. After a moment's reflection, I'd add: Sergio Aragones. W. Heath Robinson. Heck, even Wally Wood. All of them specialized in digesting the quantity of information on the New Yorker cover, but were able to draw from a wider range of picture making tools than Mr. Brunetti in order to accomplish it (at least in my opinion).

How many of the children who worship Brunetti even know these names?

David: " I need someone who understands this kind of material to hold still and, with an example of their own choosing, explain the complexity and humor to me, rather than skittering out of reach the way McCloud did."

for me, the way Ware draws and the lays out his pages is all part and parcel of the emotional tone of the work. it reminds me of directors such as Stanley Kubrick or Ingmar Bergman who deliberately choose an emotionally cool, detached viewpoint in which to watch the petty squirmings of their characters. i genuinely find moments in Ware's work as chilling as moments in the work of those two directors. or as bleakly funny.

i also think that with the more diagramatic layouts such as this, Ware is genuinely going into new formal story-telling territory, something that neither words nor traditional film language can do (most comics, despite the fact that they're drawn and not filmed, basically use conventional film grammar to tell the story. establishing shot, close up, reverse angle etc).

the detached point of view is going to put off a lot of people who want to be entertained in a more straight forward way. the fact that the layouts can be difficult to navigate and the bleak tone of the stories is also off-putting for many. but you can't please all the people all of the time.

Tom wrote: "The airplane information makes feel like I am still reading not looking."

I had the same reaction. That cover overtaxed Brunetti's organizational abilities, and reminded us why choosing priorities (and being able to implement them) is one of the most important roles for an artist.

Kev Ferrara wrote: "the robotic-infantile style actually isn't bringing all that much clarity to bear. What it is bringing, I think, is comfort to those who spend their lives immersed in text."

Kev, I have struggled against that kind of explanation. After all, the fans of this material are very bright people, people of good will who are capable of appreciating, at least intellectually, that visual art forms are not a subset of words (just as dance or music are not). So what you say should not be correct. Yet, every year it becomes harder to come up with an alternative explanation.

One might postulate several reasons for the rising appeal of this text centric art, primarily that in an information age managing information requires a short attention span and visual symbols with the shallow functionality of icons on a computer monitor. The audience for Brunetti et al was raised on the flat screen where knowledge is less important than the accessibility of information (As Karrie Jacobs wrote, with information technology our reach is infinite but our grasp is weak).

The initial spoils from making this trade off are so impressive (in terms of wealth, ability to influence the world, and the options for amusing yourself) that it is difficult to say they've made a bad bargain-- at least so far. All one really might say at this stage is that this audience is ignorant of the scope or value of what they are leaving behind (and therefore that some of their adulation and smugness is premature.)

Another catalyst for the change of course might be globalization. The image on the men's room door may not communicate much of an "idea" but it is immediately recognizable in airports around the world, regardless of the language you speak or whether you know how to read.

Chris Bennett-- I'm not sure we have fully resolved that vocabulary issue about the difference between an idea and a fact. You say that the sign on lavatory doors conveys "the idea of ‘male’ and female" but I would have thought that an "idea" required more than a physical division between X and Y chromosomes. You say that Brunetti's image of people having sex "is very basic, but that doesn’t stop it being an idea." I suppose for our purposes we might agree that there is a middle range where idea and fact overlap, but for me the litmus test then becomes, "assuming it's an idea, what does that idea get you?" If it doesn't inspire or illuminate or enrich you, if it doesn't suggest a path or a solution or give you something to build on, but merely says "humans with a Y chromosome can enter here," then what good is its status as an idea? For example, why would we hold ideas in such reverence or study them or pay so much for art with them?

Responding to your progressive list, I tend to like Sargent's watercolors more than his oils (and I feel the same way about Homer's watercolors over his oils). Also, I tend to prefer Michelangelo's preliminary drawing of the Libyan Sybil more than I like his finished painting on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. That could just mean I'm weird but isn't it also possible that a perfect example of a drawing, the Platonic form of a drawing, is better art than a B+ oil painting?

Kev: "Are all the physically robust, life-charged intellectuals dead?"

you mean has 'high culture' gone all milquetoast on us ?

almost certainly.

but this is the modern existential dilemma. if we're all just fearful, trembling creatures in a godless, indifferent universe, then what exactly is there to make manly, heroic art about ?

David Apatoff-- A division between X and Y chromosomes is a distinction. And I would say that to distinguish between one thing and another is an idea. I say this because distinctions are decisions of the mind made in order to facilitate its comprehension and thereby its manipulation of nature. Whether an idea fits the facts or not has nothing to do with its existence as an idea. The facts remain the facts whether distinctions have been recognised by a sentient being or not.

“If it doesn't inspire or illuminate or enrich you, if it doesn't suggest a path or a solution or give you something to build on, but merely says "humans with a Y chromosome can enter here," then what good is its status as an idea?”

An idea may have low status in this sense (for example: a ring of Condor feathers hung above the bed to catch one’s dreams is an idea that is utterly useless), but I can’t see how that disqualifies it as being an idea.

“That could just mean I'm weird but isn't it also possible that a perfect example of a drawing, the Platonic form of a drawing, is better art than a B+ oil painting?”

Yes, absolutely. That’s what I meant by the Klimt drawing being better than the academic mural of The Wreck of the Hesperus. My contention was that an A+ masterwork using the full gamut of graphic means available is by definition going to contain a more comprehensive range of depth than an A+ drawing. Otherwise, why bother messing about with nasty smelly oil paint and expensive canvas and big studios? Why not just do it all with an HB pencil on a scrap of newsprint?

The style Ware and Brunetti use tries to evoke something else that is not in the page, that is located in our memory. They are inviting us to do the famous "closure". But I think they fail to see the drawing in comics as a thing in itself.

The same happens with sound it music. It may evoke memories, feelings and new thoughts, but they are also sounds in themselves.

The drawing as typography thing, that is meant to be seen and read and the same type is comics trying to be words, literature. But what comics does best is representing the imagination, not just evoking memories.

If you want to really undestand what Ware is loosing with his approach to comics read one good strip of Amy and Jordan, by Beyer.

He is evoking feelings and memories, he is clear, he has rythm but at the same time he is showing you a world with lines that is a thing in itself.

That is not looking like a typographic catalog. I agree with the author of this post that what Ware and company are loosing is the INDIVIDUAL approach to the drawing in comics, which is what defines, mostly, art. The individual.

I think that that kind of approach is a popular art trying to be high art again. The same old story once again.

I think what the article is missing is a real understanding of how comics work (up to the date at least).

MORE DETAIL: Is good for an author who wants to represent his imagination. Or an author who doesn´t want to use too much words in his comics.

LESS DETAIL: Is good for an author who wants to put all the strength in the idea and doesn´t care too much about his imagination being represented. Also good for someone that uses a lot of words in his comics and wants to have a nice balance.

Ware is not someone who wants to tell you too much about his imagination. He just wants to share the basic ideas. Curiously he loves Herriman and Crumb.

I don´t agree he is not too good at drawing. Read his sketchbooks.

but this is the modern existential dilemma. if we're all just fearful, trembling creatures in a godless, indifferent universe, then what exactly is there to make manly, heroic art about ?

This "cosmic perspective" is quite a presumptive one for a human being to take. It is the fallacy of scientism that whispers in our ears that we know much of anything about anything. Rank foolishness, as I see it. We don't understand the present or the past any better than we understand the future. We don't understand reality in the least whether it is computed, holographic, all in our heads, recursive, refractive, paradoxical, merely energy trapped by geometry, or what have you. We don't even understand how gravity keeps us from flying off the planet. In the great long run, with unfathomable epochs of time, who is to say that we can't defeat aging, defeat physics, defeat the weaknesses of biology, transcend the smallness of our scale, defeat the heat death of the universe, and on the way defeat this terribly corrupting meme of meaninglessness which saps the will and joy of so many...

In the meantime, in the only real perspective we can know, meaning (Pragmatist version) is the consequences we intend to produce on ourselves, those around us, our town, our society, our world, our solar system... There are still battles to be won on so many fronts it boggles the mind. And thus still heroes to champion, and opportunities to develop metaphoric heroes to represent the struggles of our tribes and species. Just as Tarzan represented a particular kind of struggle during the peak of industrialization; as Batman did for corrupt and cramped modern metropolises that towered up during the 20th century.

This is not to say that there is no drama in the quotidian events of the everyday. There is. But the emphasis on the quotidian and childlike seems to me to be evidence of an abdication of the larger responsibilities we have before us. And the larger thoughts, the steelier determination, and the greater physical and mental courage required to tackle them. If all our "unacknowledged legislators" are pusillanimous twerps, the future of the west is doomed. And what of that infant... that meaningful intrusion into all Ware's meaninglessness. How narcissistic to bring a child into the world to fill up his emptiness, only to bequeath a meaningless hell to them outside the walls of the home? A hell that they must eventually meet. This is why navel-gazing is selfish and immoral and why it is to be despised.

The information graphic tells us something in a way that no actual conversation can take place. It's like answering recorded computer prompts on a telephone where the conversation is not really a conversation at all, though there is some kind of transfer of information.

Art is a third person between two people where subjectivity plays is central to what makes it art and what makes conversation a conversation. We communicate with this tertiary intermediary place called a conversation or art which doesn't quite exist in either party.

The New Yorker cover with the isolated people in a park is telling us how each is seeing the world through a different gadget or their own lens, filter or training. It's an ideological speech made with info graphics and moves like someone just learning to read. The-cute-people-are-all-looking-at-the-butterfles-through-a-gadget-tee-he. Do-you-get-it? See-the-scientist-in-the-uniform-seeing-through-his-education? He-is-seeing-something-differently-than-the-artist. It's pedantic and exclusionary because it simply dictates to us what's going on. It might be appropriate for Highlights Magazine, or a Weekly Reader, where the young reader is being aided in learning to notice differences, but why for an adult magazine? I think Kev is correct that there is something infantile and condescending going on here.

The same is true with the scientists and engineers working on the new designer baby. It reads at the same clunky pace, golly-gee-whiz-look-2009-is-now-so-old. Tommy Trainer is also simply telling us what is going on. The cryptic Wares are a conflict in motion, both visually exclusionary and a kind of pretentious Where's Waldo, inviting us to figure it out, but with a hopeless ending as Kev points out.

By comparison, the Nancy comic strip was drawn from a child's horizon line, an effective device for entering Nancy's little world. It wasn't dismissive or exclusionary as are the info graphic or robo prompt. And though its vocabulary was incredibly simple, it spoke to its readers without talking at them.

Hmm. Words versus images. Maybe Tom Wolfe in "The Painted Word" wasn't exaggerating after all.

David,

Thanks very much for this. I always look forward to a new post here.

I know this isn't very generous of me, but I might have more patience for Chris Ware's deliberately ugly drawings if they expressed an idea more interesting than, "Boo hoo life sucks."

That's a really boring idea that has been done to death already and the critics who fawn over him are embarrassing to read.

Thanks again for the great blog; I've lost track of how many great artists I've discovered here.

Best regards,

Lee

Donald, yes, I know it sounds like that because I am using the word conversation as an example of a complex medium between two people to help visualize art as a complex medium between artist and the viewer, to demonstrate that art isn't like a simple binary piece of information like a chemical reaction, but that art is a separate reality made up of the work of the artist and the experience of the viewer.

A conversation is similar in that it is different than the two individual people. An info graphic can't act for this capacity as its visual is too dead and limited to trigger complex imagery and feelings.

Information graphics act in the opposite way of Tom Wolfe's criticism of endless words substantiating vapid images.

The image of the man and woman doesn't say restroom, but we literally or verbally understand or at least recognize the images as restroom for men or women. So the info graphic is acting as a replacement for the words and is not art, which is a complex medium between people.

I apologize if that was torture. Thanks.

Kev,

I've been admiring the Walter Everett you passed along my way, Sisters Pacing Two and Two. For anyone not familiar with it, it is a very tender painting of some nuns taking some physically challenged children out for some fresh air and it's a wonderful work filled with theological and mystical meanings and basically these meanings involve very delicate but quietly heroic virtues, now long dismissed and forgotten.

As I've been thinking about this painting I was reminded of a trader on the floor of the NY Stock Exchange who boasted proudly that “Capitalism had done more good for the world than all the acts of corporal mercy in history combined”.

It's a very serious statement, despite the huge amount of schools, hospitals and even some universities founded and staffed by just such sisters, many of which have since been secularized and taken over by corporate collectives. There is merit in the statement, but in short what it attests to is the vast economic, scientific and medical superstructure which has grown up around us since WWII.

I don't think the superstructure is about to give up on its goals and there are as many honors students at top science schools as available spots. Yes, many are from China, but more schools will be built and numerous state schools now have higher academic standards.

The loss of meaning Laurence John mentioned is part of the infantilism you have described so well on this post and it began in earnest with one of the triumphs of the west, the nuclear explosion at Hiroshima. It made me wonder how the delicate virtues attributed to supernatural concepts such as self giving in the Everett painting could ever have survived the world economic superstructure. Then I came across an article on 8 curious survivors of the Hiroshima blast. “Here is a Wikipedia account on the survivors who were still alive and well in 1976. Wikipedia".

I agree it is immoral to despair.

PS: Sorry, I meant to delete the word plays on a previous comment.

The problem is that thes artists look like thy can't draw, maybe they can... but from wht i see here they've given it up completely.

The aforementioned Steinberg, or i can think of some Searle stuff or of illustrator Quentin Blake or Comic artist Hugo Pratt, all show a certain Gusto and passion in bringing it down to the essentials.

These round head cartoons show no love nor passion, they are just dead flat.

Ed from Italy

Laurence John and Kev Ferrara-- I'm not well positioned to criticize pictures for their content... I like too many illustrations of dumb content myself (Coby Whitmore illustrations of 1950s women's magazine fiction, 1930s covers to Spicy Detective pulp magazines, Kurt Schaffenberger art for Lois Lane comics, etc.).

The problem is, the artists we're discussing force us to appraise their content because there's nothing particularly remarkable about the pictures. Any competent artist could easily replicate these images-- no special skill or talent required. Girls in high school have been drawing characters similar to Brunetti's in the margins of their notebooks for decades. Laurence's "diagrammatic layout" from Chris Ware strikes me as technically indistinguishable from the airline information card I posted: circles and arrows direct the flow of information, small sequential boxes with little scenes containing geometric figures with a minimum of detail, all on a white background.

So if the difference between a sensitive genius and a staff artist is not their drawing ability, it must be in the inspired content-- the message (and what Laurence might call its cinematography). Well, if we're forced to turn to the content to evaluate what's special, let's go there, and let's focus on Laurence's diagrammatic layout as a useful example.

Ware's page seems to me like a cross between a genealogical chart and a shoebox full of memorabilia. It inspires feelings of wistfulness over the fact that children grow up, old people die, and each individual who comes and goes has a personal story with its own sights and sounds and smells. It's pretty clear that Ware is a sincere fellow with melancholy moments and that he likes to ruminate about such feelings. (It is also clear that he has a better work ethic than many of the 3 billion other people on the planet who share those ruminations).

OK, so I get that Ware taps into those feelings. Where I have trouble is with the artistic value of what Ware contributes to them. I suspect I could look through any stranger's random collection of faded photographs and pressed flowers in an old shoe box and experience the same feelings that Ware tries to evoke. How do his painstaking little drawings and circles and charts enhance our experience? Does he shape the direction, timing or depth of our experience in some way? Does he explain something we wouldn't understand from the original items? Ware empties out the shoe box and lingers over its random contents (often at a slow, lugubrious pace) but do you feel illuminated by his diagrammatic layout of those contents?

Let's be specific about Laurence's linked image. Ware shows us an informational graphic of a bible in a separate panel. What does that do for you? He also has an offshoot from the timeline to show that the girl picked a flower which was later pressed in a book. Where does that go? What does it do for the viewer / reader? Fondling old army photos, medical records and baby pictures evokes feelings but it only takes us so far. I'm not looking for a linear story, but would expect to find a stronger hand of the artist (or voice of the writer) before I start crediting Ware with some worthy artistic insight. Remember, poets have been grappling with this same tristesse since Neanderthals walked the earth. If someone was hungry to be enriched by the arts on this subject, why on earth would they turn to Ware? Why not turn to Emily Dickinson or Walt Whitman (unless of course words without pictures are too steep a hill to climb these days)?

Laurence (or others who have succeeded in decoding Ware), can you point to something profound or poignant in Ware's diagrammatic approach?

Sean Farrell-- Thanks for your comments. I agree that these images seem to be "generic without subjective meaning" that seems to makes shapes more approachable and interesting. Lotte Helinga wrote a very interesting article about the transition from handwriting to printing books in the 15th century, where she described the trade offs when moving from personal, subjective letters to generic forms: "through the first half-century of printing we can see a relentless process of simplification of graphic form at work. This simplification consisted of a selection of those features of script that were essential for communication, and, conversely, the rejection of the endless variation in form and function that the writing hand can create. Written script forms can be ambiguous; there can be innumerable small distinctions in, say, the value of a capital as expressed by graphic means. In typography, on the contrary, such variation is impossible, once forms have become fixed in metal they force you to make decisions...." We may be witnessing something similar with information graphics.

Anonymous wrote: " I think they fail to see the drawing in comics as a thing in itself."

One interesting thing to me is that many of these artists-- Brunetti, Spiegelman and Ware, for example-- are true lovers and appreciators and historians of the drawing in comics and illustrations. They love that stuff, and I suspect they love it so much they have found a way to insert themselves into that world with words and thoughts, because they just can't do it with pictures.

Another Anonymous-- Apart from brief contacts in Raw, I was not very familiar with Amy and Jordan. While the words are not always to my taste, I see what you mean about the visual images. There is more humanity and definitely "world with lines that is a thing in itself."

David,

i should point out that the page i linked to that you're discussing is just one page of a 380 page graphic novel (Jimmy Corrigan). it's not intended to work as a stand-alone one page strip.

i was just using it as an illustration of the type of diagramatic layouts that Ware occasionally uses, and which i personally think are doing something new (as a narrative device) within the comic medium.

David: "How do his painstaking little drawings and circles and charts enhance our experience?"

if you really want to know the answer to the above question i'm afraid you'll have to read the whole book.

as for Ware's style (or lack of) and how it works (or doesn't, as the case may be) my first comment in this comment section explains my take on it.

After taking a good look at that piece that Laurence linked to, the info-graphic sequential-fiction genealogical representation... and thinking about that bird one (where it threatens to be run over in the last panel) I think Laurence's view has to be accepted into the overall view.

I think the merit of Ware's work is not related to illustration. And it isn't great writing, in the sense that I also don't find it insightful. It does stake out new territory in terms of developing the diagrammatic end of the comic book language. Even though, in many ways, it isn't all that effective diagrammatically.

The bible that David flagged up is an interesting entry-point into another problem with the navel-gazing egg-head mentality... their endless recursive searches for minute connections within a very small purview. Now, I haven't read the book, and maybe Laurence you can correct me on this... There is the bible with the pressed flower on the shelf in the end table, and then it is isolated out to the left, and then it is opened up, and then we see the flower inside, and then we see the flower before pressing, and then we see the blue-dressed mother as a young child picking the flowers, and then we pull back to the long horizontal (backgrounded panel) of the homestead.

Essentially what Ware is doing here is unpoeticizing or untranslating something that is much more economically said in english as approximately; "the bible with the flower she had pressed, the one she had picked from the lawn as a child, was tucked in the kitchen end table as she raised her own child." And I believe he is diagramming this out in visual prose in order to demonstrate that anything you can write in English can also be written in graphics without resorting to words.

Now, a great many illustrators, comic book artists and graphic designers have understood this down through the years. To demonstrate it is actually a merely academic matter. And this demonstration by Ware feels academic for that reason. It seems to me to serve very little except to prove that graphics can be used as prose. This diagrammatic prose should not be mistaken for cinematic expression, although Ware is always using cinematic sequences too.

Laurence John-- The page I was referencing was not the page from Jimmy Corrigan (your first link) but the second page, the one you cited for its diagramatic layouts. That's not from Jimmy Corrigan, I believe. (I would not feel comfortable mouthing off about Chris Ware's work if I had not paid my dues and read Jimmy Corrigan from cover to cover. I found it very slow going, in part because the drawings hurt my eyes-- literally.)

I think Ware's drawing has improved since then, and his later work, such as Building Stories, comes in smaller doses so I don't find it as stultifying. Your diagramatic layout piece, which is apparently from a later period, was more interesting to me than the Corrigan page.

Don't abandon me on this, I beg you, because I view you as my single best opportunity to "get" Ware's work. The vast majority of the critiques of his work on line are so fatuous they just make me angry at Ware. (For example, take a look at http://blog.1979semifinalist.com/2007/11/02/hands-down-the-greatest-movie-poster-of-all-time/ where the writer begins, "Chris Ware is a god among men, it’s good to see EVERYONE is finally getting this." This sentence is her opening to an article on why Ware's first movie poster is "Hands Down The Greatest Movie Poster Of All Time." But there's no effort at honest analysis, no thoughtful comparisons to other relevant artists or to historical styles, just adolescent drivel. Angry commenters who have written in to this blog in the past haven't done much better. ) I assume there must be something special in Ware, and like Diogenes I am looking for one honest man who can help me with it. So far you are the brightest, most articulate and patient advocate I've come across so you're stuck with the job.

David,

the diagramatic page is from Jimmy Corrigan too... it's about 20 pages from the end.

more soon.

That's what I was trying to get at, that the info graphic is literary in function but a pre-verbal language of grunts and groans, simple recognitions, directives without visual relief or inflections and so instinctively repulsive.

I guess some people find these same raw qualities cryptic and fascinating.

Laurence John-- I found the page in Jimmy Corrigan, thanks. Good golly, that's ol' Amy Corrigan! It has been so many years since I read Jimmy Corrigan, I didn't recognize her but I took advantage of this opportunity to go back and re-read the 50 pages leading up to the page you linked, thinking they might shed some light on the page we're discussing. In my view, you definitely picked the best of the 50.

I though Ware's snow effect was nice, and most of those pages with snow had a nice mood and palette to them. I was also grateful that none of figures were from his "circle head" period which is the subject of this post. But other than that I had a hard time finding a single drawing in those 50 pages that I enjoyed or respected.

A huge percentage of them were repetitive drawings to slow the passage of time-- a pacing tool which I think could work well if it was used judiciously as a contrast to "normal" pacing, but which, when overused, turn the reading experience into the Bataan death march. I think that long, slogging march is part of my problem with Ware that I should attempt to put aside for purposes of this exercise-- he asks such a mountain of effort for what seems like a mole hill of a pay off, it's difficult for me not to feel cheated for my time commitment. That, plus I am trying to get over being irked by the fawning "Chris Ware is god" crowd that is so laughably ignorant of the recent history of graphic arts. Those two ingredients have probably combined to put a chip on my shoulder that isn't helpful for any kind of objective analysis.

David, i think if you don't 'get' Ware by now there's very little hope that i can change your mind at this stage. He seems to be one of those artists you either 'get' or don't.

i could place Ware in a tradition of writers such as Vonnegut, Camus, Beckett, Céline, Dostoevsky, Kafka etc. writers who also take a look at sad, pathetic, desperate individuals. but that might sound like i'm trying too hard to attach some of their cult status to him. it might sound too fawning. besides, if you're not a fan of writers who deal in the existential, the absurdist, the alienated, you're not going to like Ware.

a lot of people complain that his work is all just misery, and why should they spend their time reading about an insignificant loser such as Jimmy Corrigan ? well, do we steer clear of fiction containing murderers, rapists, madmen, thieves and good-for-nothings simply on the basis that we don't wish to spend time in their company ? of course we don't. literature is full of wretched creatures.

so how would i validate his work to those (like Kev) who say that there's nothing heroic or insightful or illuminating about any of it ?

well, i don't think that the sad lives of losers is what the work is really 'about'. nor do i think that the message is "everything is hopeless". there are frequent digressions which contrast the petty / ultra-mundane aspects of modern life with the beauty and dignity of nature. there are many passages which linger on the passing of time, weather, or the changing of seasons. (what would be called 'the sublime' in other artist's work seems to go unnoticed in Ware's). the sad, unfulfilled lives of most of the characters are always juxtaposed with a zoomed-out viewpoint of something far grander; the whole universe. it reminds me of something like this from Ernest Becker's 'the Denial of Death':

"if he gives in to his natural feeling of cosmic dependence, the desire to be part of something bigger, it puts him at peace and at oneness, gives him a sense of self-expansion in a larger beyond, and so heightens his being, giving him truly a feeling of transcendent value"

it's as if Ware is saying "this is what life is. the mundane and the cosmic. both happening side by side, but usually oblivious of each other"

---

anyway, that's why i think he's a good storyteller. more on the drawing part later.

Laurence John-- This is a language I can relate to. I do admire the writing of Vonnegut, Camus, Beckett, Dostoevsky, Kafka etc. (I've never read Céline, but looked into him and now I understand why. That boy was cray cray.) Perhaps my admiration for these authors is part of the problem-- I see how beautifully and intelligently the alienated and the pathetic can be handled, and it makes me wonder why anyone would settle for Jimmy Corrigan.

For example, Vonnegut (who for me is the most enjoyable read of the bunch) may write about sad disaffected people but he captures their predicament in a sharp, coruscating prose laced with humor. There are gems on every page. Dostoevsky is slower and tougher going for me, but each sentence is incisive and you always sense a shining intelligence and profundity behind his writing. None of the writers you mention make the mistake of portraying bleak, desolate lives in real time. There is a firm, discriminating editorial hand behind each of their works.

I wouldn't expect Ware to try to use the full vocabulary of these authors in a comics medium, but I would expect him to make effective use of grouping and sequencing and economy and staging. Do you see some compensating strength in Ware in these categories? Ware's pacing makes me restless. In Jimmy Corrigan, he stretches a visit to the doctor's office into 450(!!!) panels. (And if you think it took a long time for me to count all those panels, imagine how I felt about reading them the first time.) Some of those 450 panels are devoted to fantasies about the nurse or comments from Jimmy's father, but Ware also devotes a huge number of the panels to a bird outside the window, or to the crinkling of the paper on the examination table where Jimmy sits. Whenever Jimmy's father coughs, that's a whole separate drawing. In fairness, sometimes Ware squeezes a "koff kaff" into one drawing. (Panel one: doctor enters the examining room. Panel two: doctor moves a chair ("squeek squeek"). Panel three: doctor washes his hands ("sssshhhhh"). Panel four: doctor opens a drawer labeled "towels." Panel five: doctor dries his hands with the towel. Panel six: doctor disposes of towel in a drawer labeled "used towels." Panel seven: the doctor finally begins to speak.) Which of the authors you mentioned would pace their stories that way? Dear god, carbon based life forms aren't meant to survive at that pace.

It is possible that the quality of the drawing makes me more impatient. I have infinite patience for spending time in the company of rich, rewarding drawings. But Ware clearly doesn't want us distracted by (or taking refuge in) the images that move his story forward. His flat, hardscrabble drawings truly are informational graphics. Ware has to label those drawers "towels" and "used towels" because readers couldn't tell what the doctor was doing from the drawings alone.

I think it's fair to ask whether I am being too impatient with Ware because I don't like dwelling on the sad lives of losers. I do have a natural fondness for heroic responses to squalor (Kollwitz over Grosz). Yet, I love Dostoevsky's Notes from Underground, and you can't beat that for degradation and squalor. If Ware's pages were numbered, I would ask you to point me to the "grander," "sublime" passages. (After all, I missed Amy Corrigan on your diagrammatic layout page.) The theme you've distilled into one short passage ("this is what life is. the mundane and the cosmic. both happening side by side, but usually oblivious of each other") seems to me a very worthwhile subject for a book the length of Jimmy Corrigan. I only wish that Ware wrote with your focus and ability.

Anonymous / Lee wrote: "I know this isn't very generous of me, but I might have more patience for Chris Ware's deliberately ugly drawings if they expressed an idea more interesting than, "Boo hoo life sucks."

I have that same ungenerous impression of Ware's overall tone-- that he tends to offer a cringing view of the world which high school literature students mistake for sensitivity. But Laurence John, who impresses me as a straight shooter, writes, "i don't think that the sad lives of losers is what the work is really 'about'. nor do i think that the message is 'everything is hopeless'" Since I am here to learn and not just to talk, I am looking forward to focusing on Ware's take on "beauty and dignity of nature" and his "zoomed-out viewpoint of something far grander; the whole universe." Those elements, even in limited quantities, have potentially great redemptive power.

Anonymous / Ed from Italy wrote: "The aforementioned Steinberg, or i can think of some Searle stuff or of illustrator Quentin Blake or Comic artist Hugo Pratt, all show a certain Gusto and passion in bringing it down to the essentials.

These round head cartoons show no love nor passion, they are just dead flat."

That, for me, is the heart of this post. We can put aside Ware, and politics, and the words and themes of modern stories, and just focus on the marks on paper. There is indeed a gusto and passion to the lines of artists you mention that is simply absent from the circle heads of Brunetti, Gauld and Ware. I am certain that the current artists love the artists you mention, and the New Yorker used to hire such artists, but I agree that today's circle head work is "dead flat."

David:" But other than that I had a hard time finding a single drawing in those 50 pages that I enjoyed or respected"

David, when i buy comics it's usually for the art rather than the storytelling. i own foreign comics which i cant even read which i bought just for the art. when i flip through the 380 pages of Jimmy Corrigan i'm also hard pushed to pick out a single panel i like in terms of drawing. there's nothing in it that makes me think "i want to draw like that !" so Ware is something of an exception for me in terms of the comic art i admire, and he's clearly doing something different to other artists i admire for their 'style'.

it all goes back to my first comment about 'transparency' of style. when we look at a drawing that has more expressive qualities, that shows variety in the width of line, and the tremor of the human hand (and a myriad of other expressive variables) i think we always view that work as having a more 'subjective' point of view. it's as if the artist 'takes us with them' into their inner state of mind as they drew the image. because Ware is trying to maintain this objective, dispassionate point of view i mentioned above, i think he's deliberately chosen the least noticeable style possible to aid that transparency.

the cool, detached point of view is necessary for the particular type of storytelling he does. the storytelling is the point. the 'art' resides not in the line-work of each individual figure. it resides in the way the story is told, in the narrative devices, the page layouts, in the cumulative effect all of those tiny panels as part of the overall experience. when i read his work i feel rather like a scientist looking through a microscope at a civilisation i don't quite understand. it's as if the events are taking place behind glass and i'm powerless to intervene. i'm sure this is due to the many distancing devices already mentioned and also the smallness of the panels. the effect can be uncanny.

i admire the overall construction of an entire Ware book, rather than each individual drawing. the same way i might not notice a particular brick in a building's facade, but when viewed in totality the building might be a beautiful thing.

Thanks for the interesting exchange on Ware and existential writers. Ware isn't one for breathing life into the mundane which is the beauty going on in the Everett image, Sisters Pacing Two and Two.

The stripped down pre-verbal, grunts and groans work as commands; look here, go there, no stop, see, think, remember, go back and so on. It's similar to the robotic prompts, computer related directives and also mind control techniques, all of which are a growing part of an unavoidable dialogue with a new existential reality.

Laurence John wrote: "i admire the overall construction of an entire Ware book, rather than each individual drawing. the same way i might not notice a particular brick in a building's facade, but when viewed in totality the building might be a beautiful thing."

I can relate to this way of viewing work. When I hold Jimmy Corrigan in my hand and flip through the pages, the totality of the building is impressive. But how do you deal with the fact that in order to experience the story, you must go through every brick, brick by brick, in sequence? How do you deal with the fact that somewhere, once every 200 bricks, is an inconspicuous brick with some minor variation that has special significance? I picked up speed because I couldn't stand the plodding pace, but then some Ware groupie would inevitably say, "Didn't you catch the significance of that bird in that small panel about 2/3 of the way through the book? It just reinforced my first impression that Ware had no clue how to prioritize, which for me is a fatal weakness in an artist or a writer.

If people were applauding Ware's elaborate constructions, ornate typography, quality materials, I would agree he is a marvelous craftsman. And based on our discussion, I'll go one step further and say he builds an excellent wall. But he doesn't seem to know how to make an interesting brick. It is hard for me to get interested in the sum total of uninteresting bricks.

What is lost if the efficient processing of information dumbs down our appreciation for visual form?

A great question and the answer is our humanity. David, Ware's merits as a mechanical illustrator and preliterate existential storyteller aside, the absence of the human hand in the geometric imagery you selected was a masterstroke of instinct and questioning regarding our new post literate and post substantial world.

The enlightenment ripped language form substance and rendered all, even morality to pragmatism and self interest. As idea began losing its substance and was deconstructed until all meaning was eviscerated, so too was the substance of art reduced and now eviscerated as well.

The sad result is such imagery, post substance visual grunts and directives. Is it a wonder people are married to their vices which remain the only substance left to them, or so people feel and are taught to believe?

This post has verified what Kev has been saying and trying to elaborate on as well as clarifying your own particular love affair with art. For me it verifies instincts which have haunted me for decades regarding pragmatism, which now appears to be increasingly replacing basic forms of manners and humanity as well as art. I know that sounds like an exaggeration, but I wanted to say this post has given a visual face and clarity to certain things which I previously understood largely by instinct and for this I'm very grateful. Also, thanks to the other commentators here too who helped sort out one thing from another.

If I may, I think the brick-by-brick metaphor is just narrowly missing the critical issue. Which is that narrative structure and architectural structure are two different things, which respectively bring different properties into a work. For the story, structure provides far more than just scaffolding upon which to loosely hang or house events. The structure itself pervades everything and has tremendous implicit meaning in terms of how the argument of the play is being articulated. This goes from the general level to the act level to the sequence level to the scene level to the beat level to the dialogue or action level of each exchange. The design is controlling everything at all levels.