For the last few days, the comics world has showered tributes to the great Neal Adams who passed away on April 28. There are many different reasons to celebrate this talented artist who transformed the comics industry.

Personally, I've always admired his fearlessness.

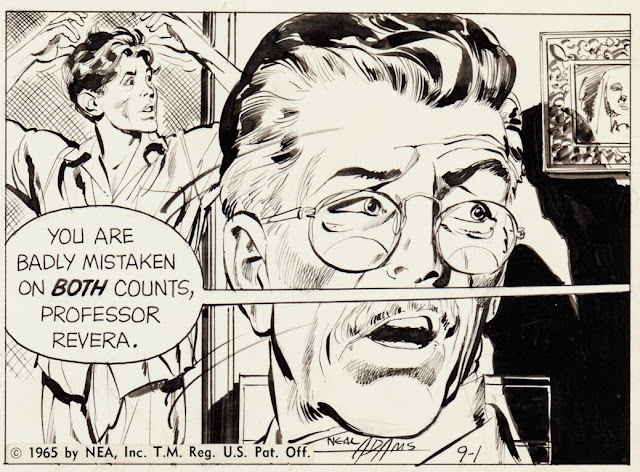

Adams applied black ink quickly and boldly-- a high risk activity. His eye invented ways to squeeze dramatic black shapes into pictures-- shapes that did not come from photo reference.

But Adams seemed to enjoy showing off his talent. Few could touch him.

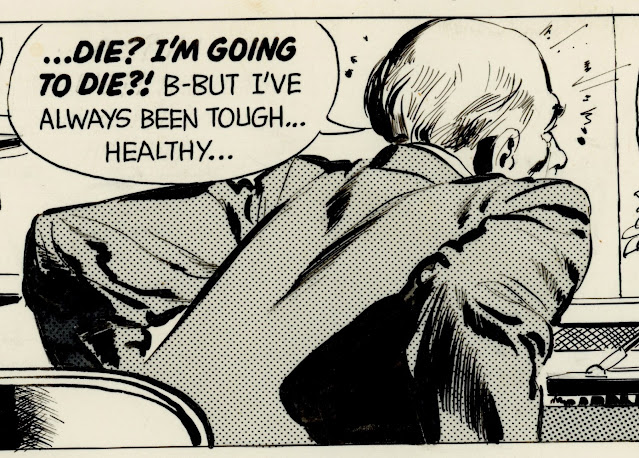

This is not to say Adams was perfect. Especially in his early years his glib, lightning fast draftsmanship sometimes trapped him in a corner, as with the placement of this word balloon:

And his brashness sometimes missed the mark in other ways. A more cautious person would've been reluctant to propound some of Adams' loony scientific theories. But that's part of what I liked about Adams-- his utter fearlessness when it came to drawing the line as he saw it.

He was a remarkable talent who made good use of his life. He shall be missed.

23 comments:

Adams was a breath of fresh air when he hit the comics scene. Along with Steranko and Smith, and a few other visionaries, comics became really exciting.

Compare this compelling stuff to the amateur presentations(wretched line work)regularly at say the New Yorker or The Nib. And folks think that's acceptable.

Adams was truly great; a certified artistic genius, a tremendous teacher and mentor, a hugely influential figure, a solid businessman, and a moral leader as well. And yeah, he was flawed. So what. So were the people he met up with. We live in a world of innumerable useless 'unflawed' people tearing down from afar and in anonymity the real achievers of society, who must necessarily be bold and a bit messy, and so always at the threshold between ambition and arrogance, achievement and belly flops, righteousness and self-righteousness. The perfectly behaved may do great and beautiful work, but they cannot lead from the front lines. Altering reality by force of will demands iron toughness; homebodies and wallflowers need not apply.

Adams' style was the apotheosis of the realistic strip illustrator style; he found the perfect level of draftsmanship, detail and abstraction for being both a realistic illustrator and a sequential comic book artist at once. Yet he never stopped respecting those who did good work in other styles.

There are so many stories about Adams worth telling, but none of them matter next to the gift of his work. For my money, he was the greatest American comic book artist.

Rick-- I agree. I remember when Adams first began to show up in Deadman and The Spectre. I didn't know who he was or where he came from, but it completely transformed my comic buying habits. I scoured the newsstand each week for more of those lovely drawings.

Higgs Merino-- Agreed. I'm open to a wide variety of styles in places such as the NYer or Nib, and I find some of them very good, but you don't see a stand out talent like Adams. Nobody even tries.

Kev Ferrara-- Yes, I agree Adams was "truly great" in many ways. He did great things for the industry and for some of the more vulnerable artists who were mistreated by the industry. I don't know if you ever had a chance to sit and chat with him at a comic convention, but it was always time well spent. Some people found him arrogant but my personal experience was that he was always humble, friendly and accessible. I was once at a comic convention when fans were swarming over Al Williamson and Gil Kane for free sketches, and Williamson said, "It's a shame that Neal Adams isn't here because Neal is very good and very fast. He could take care of all of you."

I would say that Adams was "the greatest American comic book artist" working in that style ("the apotheosis of the realistic strip illustrator style"). There are others who made big contributions in a very different way (such as Jack Kirby's muscular style, so good at force).

I don't know if you ever had a chance to sit and chat with him at a comic convention, but it was always time well spent.

I assume your conversations with him were different than mine. Back when I was first showing my work at conventions, it was nowhere near the pandemonium it is now. You could spend the day getting direct feedback from not only editors, but also the likes George Pratt, Jeff Jones, Al Williamson, Mignola, Schulz, Hughes, etc.

At Neal's table there was always a crowd standing around listening to him holding court and it was a lot harder to get to talk to him. To get your work under his eyeballs and hear his advice you had to get through a gauntlet of Continuity associates (some of whom were his kids) who did preliminary checks on the art to see if it was even worth his time. Once you got through and you were talking comics, art, and your precious precious work with the master, it was like being in the eye of the hurricane. Because he was a tremendous force both intellectually and physically; had no time for bullshit and said everything straighter than anybody you'd ever met. And a whole crowd was standing around for the show.

I had the great good fortune of getting his advice on a number of occasions. Some of the penetrating things he said still ring in my ears; that which made we wince no more or less than than that which bolstered me. All gold in retrospect.

Some weren't so lucky. I'll never forget the experience of witnessing from only a few yards away a friend who came to Neal's table for artistic advice and a pep talk. As Neal was joyfully and boisterously expounding about the history of Batman's costume to those gathered around, my friend's work made it through the Continuity gauntlet and his pages were dutifully plopped into Neal's mitts.

Neal stopped holding court, glanced down, and frowned at the first page. Then the second. Then he started flipping through the stack, almost robotically, clocking each page in precisely two Mississippis, then flipping to the next and re-clocking. And you could see his mood get darker and darker with each passing moment. With three pages to go in the pile, he gave up and laid down the lot.

He tilted his head to one side and slowly looked up at my friend and glared, the whole crowd silent and still.

"What is this shit? Do you think this crap is going to get you work? Are you falling asleep at your drawing board?" My friend froze. The crowd stared at him, aghast. He went ghost white and his hands started to shake.

Neal then raised his voice and began berating; barking everything I know my friend secretly did not want to hear; all his most deep and dreaded fears about his work and life and in front of thirty strangers hanging on every word. It was just brutal. And sad. And embarrassing. And every word was true. (I knew it was all true because I knew my friend. Neal just intuited the whole story correctly from one glance at him and his work.)

When Neal finally got around to technical matters, he told my friend to immediately abandon everything he was ever taught. "Use only photos! Never draw from your head again!" he told him. Then after a few more points he also commanded him to "never draw with ovals again." To "only use straight lines and sharp angles from now on."

"Why?" my friend shakily asked, the first word to escape his shivering body since the verbal barrage began.

"Fuck you! Because I'm Neal Adams!" came the explosive reply in a shout that was so loud it actually echoed twice in the hall.

when I think "artist should be insane" he is what I mean. RIP to a genius

Kev Ferrara-- yes, our conversations with Adams were very different (although it seems you agree that the time was still well spent.)

I believe in tough love for artists, and that was certainly Adams' style, but it sounds like he could be gratuitously cruel, and that I don't agree with. Perhaps he was tired or exasperated that day.

I was surprised to encounter Adams sitting alone at a hotel breakfast shop before Comic-Con opened. I made some joke about discovering "a star in the firmament of comic art at a breakfast buffet," and he responded with a big smile, and paused for a brief "aw, shucks" conversation. Very self-effacing and congenial. If I'd started sketching on a napkin and asked him for a critique, I'm sure the temperature would've dropped rapidly. On another occasion, I was with a member of the press who Adams wanted to impress, so he had reason to be on his best behavior. That was a long, smart interview and it even covered Baldo Smudge.

As for, "Fuck you! Because I'm Neal Adams!"... Wally Wood once gave a similar response to an editor at MAD Magazine who questioned a drawing Wood turned in during his declining years. And Stan Drake gave a similar response to another talented cartoonist who tried to make a helpful suggestion about an approach in the 1960s. Maybe a hermit's job erodes our social skills.

Caterina Gerbasi-- Yes, RIP to a genius indeed.

I'm a 'warts-and-all' kind of guy. Everybody I respect, and everybody I know and love/appreciate has huge faults including me. As long as somebody doesn't screw me up and over in a material way (stealing from me, usurping, reputation savaging, rumor-starting, arrogating unwarranted authority over me and what I am allowed to do and say, etc.) I'm fairly unfazeable.

I like big characters; real personalities. I like the boisterous; the tummlers and goofballs, the hilarious slobs as well as the incisive wits. For me talent, joie de vivre, humor, playfulness go a long long way. I can withstand a ton of insult for a few funny gems.

Humorlessness, self-righteousness, pearl-clutchers, 'Karens', the timid-but-hateful, the obsessively political, and would-be Cassandras of all stripes... they can all go play in traffic next to a volcano. I'll take the gruff genius who actually cares and does; the Neal Adamses of the world any day.

Which is not to say I'd like to spend too much time in that lane. Big personalities fatigue me easily. But I wouldn't give them up for the world. As far as I am concerned, we need every different type of person we can get to make the world interesting. If everybody was just like me, what fun would that be?

At the time of Neal Adams' evisceration, that friend of mine was still helpable. I knew exactly what Neal was trying to do with him and why; a form of electroshock therapy. Had he actually ingested Neal's advice and embodied it, in every regard, really, he would have been far far better at art as well as life for having done so. Maybe that was impossible for him, I dunno. Some kind of characterological thing; blood from a stone and all that. But Neal sure cared enough to give it a go.

So your friend was not Frank Miller ?

Kev what did your friend do? Was Neal's advice helpful or hurtful?

Al, no, nobody you would have heard of. (I understood that Adams and Miller were friendly and had mutual respect for one another. Is that your understanding?)

MORAN, the advice tucked in with the electroshock was good stuff, hard to come by at that time pre-internet. In fact, I learned about drawing with straights and angles (had no idea about Bargue and Bridgman at the time) from eavesdropping on that bomb-dropping.

But my friend couldn't do anything with the advice. He was a steady low level journeyman type who worked in independent comics for garbage money. He just didn't have 'it'... nor the drive or will or something to make up for not having 'it'. He seemed to have almost a mental block about doing research, yet he tried to draw realistically. Meanwhile his imagination couldn't parse even sculptural form or pictorial space, he couldn't sense haptically (feeling objects in your mind as solid and voluminous).

It was just as Howard Pyle said: "If you're meant to be an artist, all hell can't stop you. If you're not, all Heaven can't help you."

It was purely by accident that I was by the table when my friend was getting his skewering. He didn't know I was there. So I immediately walked away after hearing the FU line, so my friend wouldn't see that I saw and heard that happening. So I never knew how the meeting ended.

I had another art acquaintance trying to break into comics, another big boisterous character (with a nickname that sounded like it was out of the Tarzan books). He also met with Adams' wrath in front of a crowd at the Continuity Comics table. But instead of withering under the stress, this friend went on the attack, called Neal the worst names and fought like hell with him for a good five minutes. Then took his stuff, turned on his heels and left. A complete waste of everybody's time. I believe he became a tattoo 'artist.' Which, no joke, is exactly what Neal said he should do during their fight.

He was truly great. I was blown away when I first saw his interpretation of Batman. The only other who had the same affect on me was Frazetta with his Conan covers.

Hey Kev , I didn't really think he was , but recalled an interview with Miller recounting meeting Adams repeatedly and being excoriated by him , and working from his advise and evolving . Later , Adams was asked if he would like another crack at Batman , after Miller's had come out , and said he didn't think he could have added anything . There was an interview in the Comics Journal with Hogarth in which Hogarth and Adams had a clash . Spoke with Adams on the phone , along with Steranko and Ditko in the late 70's , all were very nice .

Do I recall you are planning a book on Howard Pyle ? If so , would look forward to that greatly .

Al McLuckie wrote: "Hogarth and Adams had a clash"

This raises a crucial point, I think. The problem with big egos is that arrogance is charming when it's deserved, but irritating when it is not. Unfortunately, having a big ego blinds you from recognizing when it's warranted.

Adams was certainly entitled to be proud of his artistic achievements. On the other hand, Hogarth was at best second rate (in my opinion). He couldn't stop pontificating to others about how they should draw, and cranked out one instruction book after another of bad advice. His book on drawing folds strikes me as a monument to horrible drawing. The idea of a clash between Hogarth and Adams strikes me as very funny.

In an old Comics Journal interview with Hogarth he described a portfolio project which was to feature himself . Frazetta and a few others including Adams . Adams was late with his contribution , Hogarth threatened suit , apparently didn't reach out to you , Adams sent a stick figure on a piece of typing paper as his piece . Hogarth said he went to his office with the intent of taking a chair to his head , but his daughter or someone kept him from entering .

In the interview Hogarth mentioned always keeping cash on him and that any hand that reached out to him never drew back empty - " two possibilities exist , he needs hope and I need practice ,"

In one of his early books he printed some personal work unlike his manikin figures , loose wash illos of a bull , Beethoven and stuff that hinted at more depth .

Agreed. Adams and Hogarth shouldn't be mentioned in the same breath.

Adams surely told Hogarth exactly what he thought of him. Which could not have been well met. Given Hogarth's loud self-regard and authoritarian didacticism, Adams probable enjoyed harpooning the bloat immensely.

(Hogarth's) book on drawing folds strikes me as a monument to horrible drawing.

Absolutely. We used to howl at that book. Especially the cover with Swastika Man, which was and is a 'running joke'.

Hogarth was an 'intellectual' in the worst sense. So far up his own left hemisphere he couldn't sense broadly on a bet. The few bits of his lectures online are like Maoist training camp videos. Horrifyingly rigid and controlling; breaking down everything into weirdly distorted dogma. Gave me instant claustrophobia. For a man who taught anatomy, I can't help but wonder if he ever took a life drawing class. What a grind of a mind; an Artzybasheff who thought he was a Hal Foster.

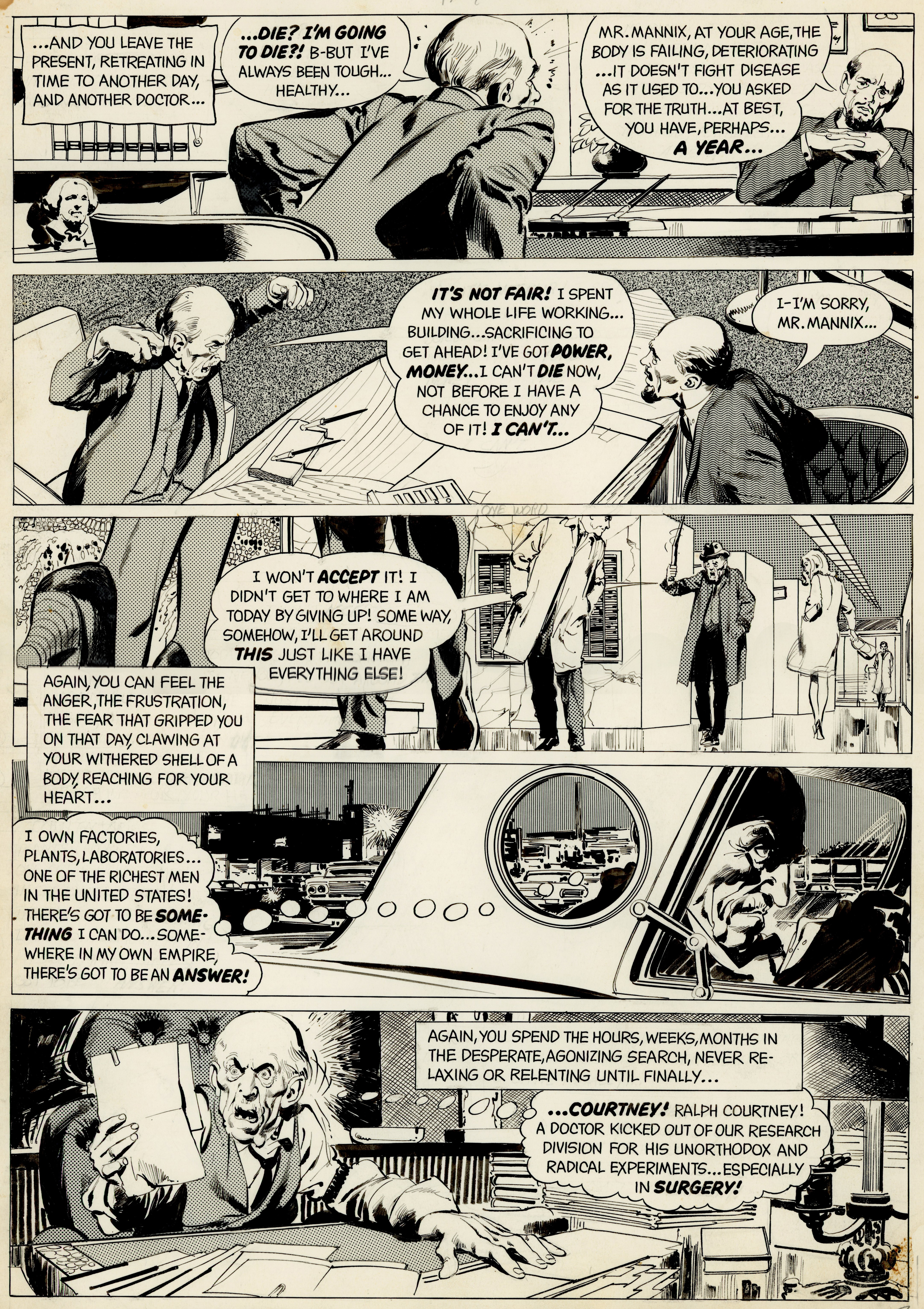

On the other hand, when I break out my Adams X-Men books it still surprises me how much he had going on at top level. He blew open the doors of the medium; he took the action and compositional romanticism of the Golden Age artists and scaled it out so it not only applied to the panel, but to the page as well. Nobody was on that compositional level, not even Kirby. (Well, Toth was.)

Then he also brought along the expert realistic drawing of the 40s and 50s literalists, the inking conventions of Raymond (plus a bunch more of his own invention), added in camera distortion as an expressive tool, and also translated cinematic techniques into his work (only some of which Krigstein and Steranko had already pioneered). How could he have not revolutionized the industry?

I'm a fan of Adams , but as soon as he started inking with rapidographs , beginning with his Ms Mystic I believe , his work lost something that came from inking with a dip pen .

Oh - and in a Batman story taking place in a desert , he actually drew a lens flair in line, and it worked .

I found the Continuity Comics stuff that I looked at disturbing and ugly, artwise and story-wise. It's 'world' seemed to be heaved into being rather than developed bit by bit.

Say what you want about Stan Lee but he really had a human side to his ideas; all the great Marvel Characters were beautifully grounded. People saw themselves and their troubles reflected in Peter Parker, Ben Grimm, Matt Murdock, etc. And the story-world of X-men as a metaphor for the plight of society's gifted outsiders (however we fill in that blank) is a profound literary achievement.

Although a professional artist I have zero knowledge of the practical side of comic-book art and only a touch above that of comics in general. But one of my most cherished possessions is a beautiful original Modesty Blaise strip by Jim Holdaway for the Evening Standard newspaper in the UK - so I put my money where my mouth is when it comes to quality. All to say, I judge that complete page you shared by this Adams guy to be an astonishing work on so may levels.

Thanks for the post David!

Al McLuckie wrote: "I'm a fan of Adams , but as soon as he started inking with rapidographs , beginning with his Ms Mystic I believe, his work lost something that came from inking with a dip pen."

I agree-- that's why the theme of this post is Adams' astonishing bravery in using dramatic black inks. I think the period you describe was still admirable for its clean, tight line (better than the vast majority of comic artists) but clearly a step down from his peak. What can I say? I'm willing to forgive the Beatles for their misstep with the Magical Mystery Tour movie because on average their experiments turned out very well.

I think that in the end his frustration with the economics and the inequities of the comic art business drained some of the potential of his brilliance. He began selling fans those repetitive one page portraits of popular super heroes grinding their teeth; he tried leveraging his skills with a stable of apprentices to handle the more mundane parts of drawing. He was justifiably distracted by the theft of and profiteering from his old originals. He also tilted at some very worthwhile windmills.

Whatever his missteps, I think his legacy as a brilliant draftsman will always shine through.

chris bennett-- I don't draw a bright line between comic art and illustration (or between illustration and fine art, for that matter) largely because of talented artists such as Adams who can pretty much go where they want to go. I'm glad you share my regard for the dense page reproduced here, it has an amazing atomic weight.

Wow

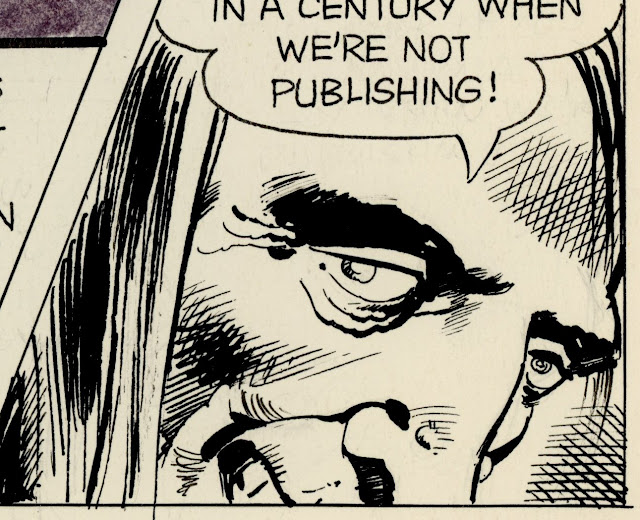

I think it's a well thought out choice. I understand that is kinda strange seeing a balloon's pipe that covers a face, but it has a reading reason: the balloon is placed there because Adams was working with Western reading direction, from left to right, which also happens inside a single panel, and at the same time he wanted to have a close-up of the person who's interested by the text, so he placed the balloon to force the viewer to read following these steps:

- to read the text inside the balloon;

- to see the surprised expression of the man and the rotation of the head, and simultaneously to follow the pipe;

- to get to the next panel.

He could have drawn a curved pipe that goes to the bottom of the panel, under the chin of the face, but I think his goal was to use the direction of the pipe to highlight the rotation of the head, and to highlight the expression of surprise of the man somebody is talking to.

Unconventional, experimental, as always Adams has been.

Post a Comment