Many of the most famous fine artists of the 20th century aspired to be commercial artists. Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Willem deKooning, Roy Lichtenstein, Ad Reinhardt and yes, Claes Oldenburg (who passed away yesterday at the age of 93) all tried to make it as commercial artists but many lacked the skill or talent.

Unlike several of his famous peers, Oldenburg really knew how to draw.

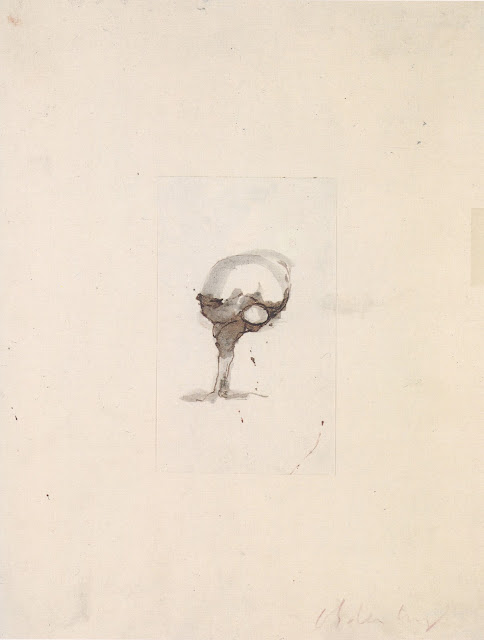

|

| Ironing board monument for the lower east side of New York |

His drawings are what I'd like to celebrate with you today.

As a young boy in Chicago, Oldenburg was thrilled by his mother's clipping of images from American magazines. After studying art at Yale, he found work drawing boll weevils for pesticide ads. He eventually moved from illustration to pop art, and then became internationally famous for his monumental sculptures and proposed public works. He proposed giant sculptures of unlikely subjects such as ironing boards, smoke, lipstick, and slices of pie. But I agree with art professor David Pagel who observed that "More often than not, [Oldenburg's] preposterous proposals were primarily great excuses to make great drawings."

For example, I love this drawing of immense dancers around a pile of other dancers:

Despite their bulk, the dancers are light on their feet. They remind me of the prancing hippos in Fantasia:

I salute any artist who can draw landscapes this well from the shoulder:

|

| Man carrying a large parcel |

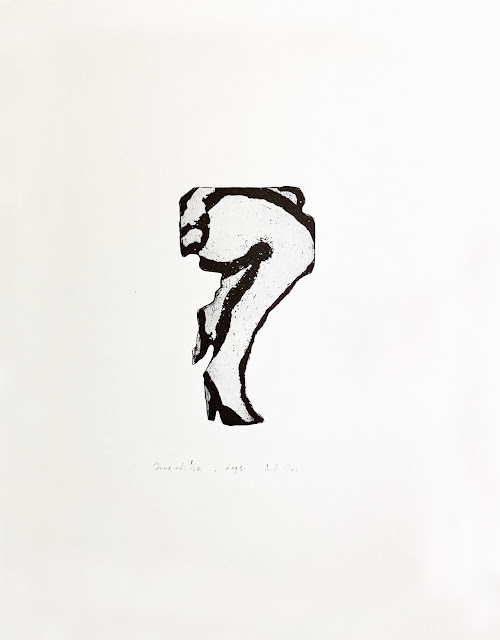

|

| legs |

|

| moon bop |

|

| ya bla with car |

Even with these child-like drawings he never lost his great sense of design.

45 comments:

I think the 'Drawing Of Immense Dancers Around A Pile Of Other Dancers' is the best of the bunch by far, but that's not saying much given the feebleness of the rest and the fact that most artists can pull out scores of sketches like this from their ideas-for-possible-paintings stash.

But thanks for the post David, it's always a treat to see a new one.

It's funny how looking at the small crops of the dancing ladies, barely legible, it's enough to see that the guy really can draw.

His line reminds of Bill Plympton's work.

kev ferrara and chris bennett-- I knew these drawings were likely to provoke a tussle, and that's fine with me. I hope to be pressed into sharpening my understanding of why they're so good.

kev ferrara-- I'm a big fan of coherence too, but we must acknowledge that coherence has let us down more than once in the 20th century. As the physicists have told us, "If you're not completely confused by quantum mechanics, you don't understand it." Surely you don't expect artists to be more slavishly deferential to an enlightenment ideal than scientists, philosophers, psychologists, or others who were dismayed to discover that the sun has set on the age of reason? There's a reason everyone isn't trying to draw like Ingres now, and it's not just lack of talent.

I'd say there are three types of drawings in this assortment from Oldenburg, and it would probably help our analysis to sort them out: There are drawings such as "legs" which I view as the work of a designer; there are drawings like moon bop and ya bla which have a primitive, instinctual violence similar to Dubuffet's; and last there are more representational drawings like the ironing board or the landscapes. Your criticism seems mostly targeted at this last category.

For me, Oldenburg's themes such as "a giant piece of pie" are not the source of his greatness, they're just an example of his light irreverence in an era when the priests of "fine" art were being overly pretentious. His monuments to a cigarette butt or lipstick were a way of flipping off the art critics, wealthy collectors, gallery owners and museum curators who took themselves SO seriously. Those groups also turned up their noses at illustration and comic art, so you can hardly expect me to fault Oldenburg for irreverence.

Which brings me to his more representational drawings. If you look at the giant ironing board, you can see from the perspective of the board, the shadow it casts on the city scape below, the treatment of the buildings and the winding river, that Oldenburg knew what he was doing. The same with the distortions to the anatomy of the immense dancers. But stylistically I especially like his great swooping lines in the clouds over the ironing board, or those bold, fluid landscapes. For me this is one brave draftsman, with strong powers of observation and a lot of character.

chris bennett-- Of all the adjectives I might consider for Oldenburg's work, "feeble" is probably the last in line. They strike me as works of great confidence. I've seen thousands of landscapes where an artist carefully chips away at a scene using a pencil point, but it's far less common to see the broad spectrum of marks in Oldenburg's landscapes-- purposefully using the flat side of a charcoal or litho crayon in combination with lines pressed hard and dark or light and feathery, parallel stripes, stray wisps or smears-- all rendered at breakneck speed while pinning down the essential features of a landscape.

The same with "ya bla," more potent, scary and striking than the later neo-expressionism that made Basquiat and others famous.

I don't disagree that Oldenburg's looseness bears some resemblance to "scores of sketches from [an artist's] ideas-for-possible-paintings stash," just as Dubuffet's drawings bear a resemblance to children's drawings or the art of the insane. But I think it's to his credit that he found elements of the wildness of those early stages worthy of display. How many of those artists you mention drained the life out of their early drawings with layered, intellectualized, introverted productions?

I must admit I admire your flights of eloquence most when you attempt to verbally elevate the rudimentary artistry of high-status frauds.

But, as was understood since antiquity, the thing speaks for itself. Even if it mumbles. (Maybe especially if it mumbles.)

----------------------

You claim that you are a “big fan of coherence” (and reason) but (both) have “let us down.”

Well okay, now and again, we get “let down.” But so what? Let's keep things in perspective: Words let us down all the time, yet you keep talking and typing. Medicine let’s us down all the time, yet you keep going for checkups and taking your meds. Your wheels will go bald sooner or later on your car, but you keep driving to work.

So what’s your actual claim behind all the science-tinted verbiage?

That because we don’t understand the quantum realm, a recently deceased artist’s inchoate mind burbles should be taken as signs of “greatness”?

What kind of argument is that for somebody who claims to be a “big fan of coherence”?

----------------------

Oldenburg's themes such as "a giant piece of pie" are not the source of his greatness

His “greatness” is entirely without a ”source.” It’s a dry well. Down which one only hears the echo of one’s own dulcet voice. As is the case with all Projection Tests.

xopxe-- It's funny, but that was one of my first clues that I shouldn't just brush this artist off. Those figures are drawn in loose, wiggly lines that dissipate into nothing, and yet it's unmistakeable: there is the turn of a wrist, a bicep interlocking with the muscles of the forearm, the spread of fingers, the tilt of a head, and most of all an understanding of the weight and balance of the body. It's all there in a quicksilver line.

nodnarB-- That hadn't occurred to me, but you're right! I'm a fan of Plympton too.

kev ferrara wrote: "So what’s your actual claim behind all the science-tinted verbiage?"

I suppose my claim is that we should take coherence as far as we can, and maybe even an inch or two farther, past the point where we've already fallen off the edge of the earth, but in the end we need to respect what fact-finding and truth-telling reveal about the tools of our coherence.

It's not just that quantum mechanics re-opened a closed world of physics to the hugeness of being. Around the same time, psychologists Freud and William James unearthed the subconscious underpinnings of what we once thought was a conscious thought process. And philosophers didn't want to go from the categorical imperative to existentialism, they were dragged kicking and screaming, and have been looking for a way out ever since. We should not expect art to remain static in the context of all that cultural change. I think I've previously quoted Bernard Wolfe here who wrote: "Art makes order out of chaos, do they still teach that hogwash in the schools? It’s liars who give order to chaos.... When do you see Dostoevsky laying out his reality with a T-square?"

I'm not suggesting that these fissures should become the central tenets of art. After all, quantum theory is only relevant at the far fringes of our experience. Their existence should not cause us to abandon our standards but they should remind us to be humble and open minded, to continue to explore and explore. Maybe we'll have to work a little harder to come up with meaningful standards in places where the wound in our coherence opens us up, without being fatal to coherence.

Applying that standard, as well as your standard that "the thing speaks for itself," I really like moon bop and ya bla. I like Dubuffet. I like Basquiat. I recognize that your mileage may differ, but that's what these discussions are for.

His monuments to a cigarette butt or lipstick were a way of flipping off the art critics, wealthy collectors, gallery owners and museum curators who took themselves SO seriously.

As far as ‘flipping off the art critics’ with his paper-deep Pop art, that’s the kind of reactive petulance (writ large and in public) that needs to be dustbinned.

Cynicism in the arts, especially when pushed upon and paid for by the public, is the lowest form of nihilism. A waste of human resources and an artistic dead end; no matter what apologetics or appeals to authority, theory, or status are marched out in its defense.

And philosophers didn't want to go from the categorical imperative to existentialism, they were dragged kicking and screaming, and have been looking for a way out ever since.

The ‘existentialists’ of various stripes starting sending out the memo to the global Arts and Letters and Education community in the 1910s that “Truth was Dead.”

Then the linguists stopped trying to kill Truth in the 1970s, finding that it was impossible to remove it from the study of language. (They didn’t bother to send out that memo, however, as is typical of those who mediate the smart sheep.)

We were told (TOLD) without evidence mid-century that – contrary to all prior aesthetic teaching about the essential similarity of the human perceptual basis as it pertains to the apprehension of pictorial effects, and significant abstraction - all meaning in the arts was based on prior exposure to style and genre. All art was thus, not ‘universal’ at all, but subjective and based on cultural/tribal programming.

Then just this past year, a study was quietly released saying, “oh, actually people react pretty much the same to basic aesthetic phenomena.” In other words, Mucha, Brangwyn, Fechin, Pyle and Dunn (among so many others) had it right all along. And Heidegger was an arrogant fraud who was believed because, well, he had the right things to say for his doctrinaire milieu.

If you want to give credence to credentialed hot takes delivered in the Voice of God style, you go ahead. But, as I see it, only truth deserves credence.

Bernard Wolfe wrote: "Art makes order out of chaos, do they still teach that hogwash in the schools? It’s liars who give order to chaos.... When do you see Dostoevsky laying out his reality with a T-square?"

The amount of strawmanning and BS that continues to pass as argument among supposed intellectuals is brutal to confront.

As if Dostoyevsky hadn’t supremely ordered his narratives to the point of orchestration. What is this Wolfe man talking about? Except arguing (victoriously of course) against his own denuded and reductive definition of order.

Point: Chaos and Order are intermingled. Ask any landscape artist (or philosopher) worth his salt.

When the narrative/fiction artist installs order – when the work is composed and orchestrated to produce its plot logic and desired effects, this composing is not “a lie”. For the fiction is not presented as journalism, but as contemplatory aesthetic experience that hints at something universal to human experience.

(When fiction is presented as journalism or vice versa, that is the lie.)

Most of what is thought of as “Chaos” is actually not. As has been demonstrated by the work in Emergence Theory, Systems Theory, Chaos Theory, and many other fields of inquiry. If it can be generated from something like source code, a rule set, or a suite of givens and algorithms, it is only seemingly chaotic.

The world is full of patterns, recurring and recursive, morphing and thematic, if we have the sensitivity to notice self-similarity through time, space, and scenario. Anybody who says differently is either gaslighting or blind.

To distinguish the significant patterns from the insignificant, at the basic level, is the pragmatic province of sanity.

At the profound level, it is the purview of genius. (Which one now sees written as “genius” – because such hierarchical words are to be held sniffily and with tweezers in the flatland of postmodern relativist ideology; where only the relativist himself is superior.)

kev ferrara-- I don't know why "art critics, wealthy collectors, gallery owners and museum curators" deserve an exemption from the world's insults. Subversion daily challenges everything else in the world; old values are constantly being eroded by new ones; granite mountains are eroded by wind and rain. Why should Oldenburg be "dustbinned" for his irreverence toward overblown organizations already famous for their cant, self-satisfaction and dishonesty? I can't think of a more deserving target.

Once upon a time Manet was criticized for his irreverence in painting working class girls when everyone knew that aristocracy was the only suitable subject. As long as the drawing is good, it doesn't bother me that Oldenburg offered a used cigarette butt as the subject for a monument.

You say, "the linguists stopped trying to kill Truth in the 1970s," but if there was ever a gelding school of philosophy it was the linguists. It's true that they did their level best to resuscitate truth and meaning, but their word games never advanced the ball. Their rational system started with an unexplainable miracle (the development of language) and ended with an unverifiable process that never offered prescriptive responses to any of the crucial questions that drove philosophy from Plato through Nietzsche.

I agree that "only truth deserves credence" and as soon as you work that out with Pontius Pilate please report back to me.

"As if Dostoyevsky hadn’t supremely ordered his narratives to the point of orchestration....When the narrative/fiction artist installs order – when the work is composed and orchestrated to produce its plot logic and desired effects, this composing is not 'a lie.' For the fiction is not presented as journalism, but as contemplatory aesthetic experience that hints at something universal to human experience....At the profound level, it is the purview of genius."

I assume by your comments you believe Dostoyevsky's greatness as an artist to be incontestable, at least on the technical level of narrative order, and that it is wrong and insulting to call him a "liar," given how exercised you are by Bernard Wolfe's statement that "liars...give order to chaos." Well, all aesthetic judgements are opinion, and even those with informed opinions disagree.

Vladimir Nabokov famously deplored Dostoyevsky, finding his novels to be carelessly made, sentimental, cliched, etc. Below are statements taken from "Nabovkov on Dostoevsky," an article from 1981 from the New York Times Sunday Magazine. (Nabokov had more to say in his class lectures on Dostoyevsky, one of many writers he lectured on to his classes.)

"Dostoyevsky never really got over the influence which the European mystery novel and the sentimental novel made upon him. The sentimental influence implied that kind of conflict he liked - placing virtuous people in pathetic situations and then extracting from these situations the last ounce of pathos.

"Dostoyevsky's lack of taste, his monotonous dealings with persons suffering with pre-Freudian complexes, the way he has of wallowing in the tragic misadventures of human English words expressing several, although by no means all, aspects of poshlost are, for instance, ''cheap,'' ''sham,'' ''smutty,'' ''highfalutin,'' ''in bad taste.'' dignity - all this is difficult to admire. I do not like this trick his characters have of ''sinning their way to Jesus'' or, as a Russian author, Ivan Bunin, put it more bluntly, ''spilling Jesus all over the place.'' Just as I have no ear for music, I have to my regret no ear for Dostoyevsky the Prophet.

"(A work of art) is a game because it remains art only as long as we are allowed to remember that, after all, it is all make-believe, that the people on the stage, for instance, are not actually murdered...."

In other words, makers of art are liars, taking the stuff of life and creating elaborate lies to which audiences are privy and in which they are complicit. Nabokov's opinion is that Dostoyevsky was a bad liar...yet, for all that, readers over time and around the world have been happy to believe his lies, however sloppy and slap-dash (as per Nabovkov) they are. You find Oldenburg's drawings and more finished works to be

"feeble...high-status frauds." There is no gain-saying your opinion of Oldenburg, just as there is no gain-saying Nabokov's of Dostoyevsky. But your opinion is not a fact that can be proved through your passionate argument...it is just your opinion. There are plenty of artists who I think are terrible, but there is no way I can objectively argue the truth of my opinion to those who take pleasure in those artists I dislike.

Oldenburg's oeuvre does not particularly beguile me, but I agree with our host that the drawings published here show Oldenburg to be a skilled draughtsman.

It has become common in the last 150 years to take what would have historically been an exercise for immature artists, or an early stage of a finished piece, and to hold it up on its own as a complete work.

Surely there is value in that process. We would not have fine art drawing, modern cartooning, paintings with large flat areas of color, or impressionism if artists did not question what constitutes a "finished" work.

Always, what wins the day is an artist of incredible vision and talent that stops at that unfinished state while still turning the piece into something so incredible that it speaks for itself.

Has Oldenburg done that here?

Eh, that's more than a stretch.

There's something nice in his planning and landscape doodles, he seemed to be aping several 17th century Dutchmen who's tiny sketches I'm quite fond of and I respect that. But any artist, even of middling quality, has accidentally made tiny thumbnail doodles of similar verve.

In his case, rather than trying to take those doodles to a next level, he spent his life making mind-numbing garbage "sculptures" and the post-impressionist ink drivel you included at the end of the post.

I don't think he deserves half of the praise you're throwing his way. But again, I believe in the idea that tiny sketches like this can be high art, and applaud the argument in spite of its misplaced direction.

Of all the adjectives I might consider for Oldenburg's work, "feeble" is probably the last in line. They strike me as works of great confidence.

Confidence in one's undertaking does not guarantee the results freedom from impotence. A quack can promote his wares with great skill and his patter will seduce the gullible into eagerly handing over their money. His potion is swallowed... but nothing happens.

...it's far less common to see the broad spectrum of marks in Oldenburg's landscapes--...-- all rendered at breakneck speed while pinning down the essential features of a landscape.

I'm afraid I see no evidence in these drawings of anything like "pinning down the essential features of a landscape", merely the mapping of the pareidolia instinct to elevate what are commonplace scribbles into art. Of which I've seen hundreds of thousands, many of my own included among them.

But I think it's to his credit that he found elements of the wildness of those early stages worthy of display.

I refer the right honourable gentleman to the comments I gave a few moments ago concerning the quack... :)

Mr. Cook,

Its amazing and disheartening the obvious things that keep bearing re-statement.

Not all assertions are opinions. Not all opinions are informed or sound. No two people are equally observant or learned on difficult matters.

"Skilled" is a relative term. One can be 'skilled' in a rudimentary way and still be insufficiently skilled (or talented or motivated) to do remarkable work.

One can appreciate rudimentary skills without overpraising them (as Richard does above). When we overpraise mediocrity we denigrate the truly deserving.

Although truly great work speaks for itself, many people cannot hear anything unless other people tell them what they should be hearing. And so those that denigrate greatness can completely blind many to it, which is a kind of evil in my view.

I assume by your comments you believe Dostoyevsky's greatness as an artist to be incontestable...

I didn't remark on Dosteyevsky except insofar as I pointed out that his works were supremely ordered to the point of orchestration.

In any work of narrative art, composing at the smaller scales is necessary to manifest the effects of the larger composition. So leaving aside greatness, even a merely coherent novel is necessarily orchestrated in its particulars.

And that wasn't even the point; it was Mr. Wolfe's reductive notion of order that I was attacking. As he equated artistic composing with the use of a T-square; as some kind of clunky easily observable architecture. Hogwash indeed.

"(A work of art) is a game because it remains art only as long as we are allowed to remember that, after all, it is all make-believe, that the people on the stage, for instance, are not actually murdered...."

First of all, this passage does not say "in other words" that "art is a lie." I have no idea how you arrived at that belief. And almost any talk of art as a 'lie' is signpost of posturing and petulance - unless the work in question only exists to trick the viewer into thinking he is seeing reality.

Secondly, the quoted passage is incoherent on the essential processes, qualities, and aims of 'games' versus those of Art.

Much posturing intellectualism comes from overly indulged narcissistic minds fixating on one aspect of a phenomena and building a theory out of it, while ignoring all the other aspects that rubbish the theory straight away. Yeah, Academic Mommy, who has become undiscerning in her menopausal days, will still put the theory up on the fridge. But that doesn't mean it's scholarship.

I do like "Man carrying a large parcel". It suggests the proof that Oldenurg could draw. 'Nuff said.

Wes

Why should Oldenburg be "dustbinned" for his irreverence toward overblown organizations already famous for their cant, self-satisfaction and dishonesty? I can't think of a more deserving target.

You think memorializing infighting among petulant midcentury culturistas is somehow worth filling up permanent public space with? Is worth funding?

I think that's clearly the wrong road. The whole artsy Basel fartsy milieu stinks; the most brutally pretentious and decadent tax scam going.

Visual culture cannot be in the hands of the resentful and performative talkers and creeps. They don't have attention spans, they're dismissive toward the past, they're narcissistic and status seeking and media-obsessed and mostly use Art Talk to draw attention only to themselves.

And worst of all, they're word people who can't even understand visual aesthetics - can't even see or feel it really - because the visual is not their native language. Thus they dismiss the old wisdom of real artists out of the twin terrors of ignorance and arrogance.

With any mediators in the arts we get the "don't think of yellow" problem. One gets led around by the nose as much by negative directives as the positive. And so those who seek to illustrate critical theories and those who react against them alike produce in the same cultural gamut: one line jokes, literary juxtapositions, grimdark surface effects, diagrammatic gibberish, political editorials, and other forms of postmodern banality and posturing.

As long as the drawing is good, it doesn't bother me that Oldenburg offered a used cigarette butt as the subject for a monument.

Seems you haven't thought very deeply about public art.

Old values are constantly being eroded by new ones;

Well you're half correct.

David posts a few crazy drawings and it gets crazy. Some nice comments in the exchange.

Poetry is sound and line drawing is line.

The line used in the dancers is as expansively drunk as the floating dancers and those tangled on the ground. The relationship between the line and what’s being described is what the drawing is about.

(An influence on Milton Glaser?)

The landscapes are also intentionally animated with gestural movement.

Drawings going after gesture and movement naturally want to extend beyond accurate borders and reveal relationships which often remain dead or unobserved in drawings pursuing some other authenticity. Going for gesture in drawing is a good place to learn about relational forces.

By giving the ordinary (ironing board) the Nietzsche treatment, pop art destroyed the intimacy that the ordinary had going for it. As argued above, the claim that representation in art was a but a symbol and therefore empty as was claimed all linguistic definitions, unleashed a destructive sophomoric craze which has yet to find relief and has only become more emphatically destructive as it lost its impulse control.

Beneath such arguments lives a desire for the self to reign supreme and in order to succeed it has to kill conscience and eventually impulse control. True, self and conscience are part linguistic and symbolic in nature but both are of understanding, just as recognizing shapes and everything else is of understanding, intelligible, even humbling in its complexity.

So big deal, words aren’t actual measurable objects but they parachute us into areas where imagination contends with forces of suggestion wrestling for dominance. The movie, The Sea Wolf might help shed light on the subject where at every step Edward G. Robinson attempts to kill conscience. No, it’s not a safe movie, people get hurt, but you can’t learn to ride a bicycle without a few scrapes.

Robert Cook-- Interesting. I was unaware of Nabokov's view of Dostoevsky, but I admit I find it entertaining when one great artist-- a member of the canon-- has the guts (or the audacity) to claim that another member of the canon has no clothes. Tolstoy blasted the work of Shakespeare, and Orwell came back and blasted the work of Tolstoy. I know Kev Ferara (above) insists on "the essential similarity of the human perceptual basis" and the universality of aesthetic apprehension, but I think these strong views of great artists lets a little daylight in, and encourages the rest of us to look at the gods of art with a closer eye.

Richard-- I agree with your point about what was once regarded as "unfinished" work. People have grown to see separate value and revelation in Rembrandt's quick sketches, in Toulouse Lautrec's "unfinished" sketches on crummy cardboard, in Peter Paul Reubens' preliminary studies which have a vitality that some (including me) prefer to his finished monumental paintings. I think this trend parallels a similar trend in music, literature and philosophy, as we seek truth earlier and earlier in the epistemological chain, considering our most basic tools in their most raw form.

I also agree that Oldenburg's soft sculptures are not my cup of tea (although I disagree that "he spent his life making mind-numbing garbage 'sculptures.'"

I don't know if it affects your judgment, but these are not "tiny doodles," most of them are great big drawings, which is why I said that Oldenburg drew them "from the shoulder." That is a large part of their boldness. He's not drawing the toenails on those dancers... heck, he isn't even drawing their legs straight, their legs squiggle like a 300 pound wisp of smoke, which is, I think, part of the concept here. He doesn't draw the leaves on the bushes, not because he doesn't have room in a tiny thumbnail sketch, but because those details would be adverse to the size and speed of the drawing.

chris bennett-- Don't you think that pareidolia (nice word by the way) is a very different game when we look at a painting (which, by definition has some intent) than when we look at a cloud or a rock? So much of art depends on the extent to which the artist makes that intent literal and explicit. So much of the quality of this type of art depends on the ability of the artist to suggest or imply meaning with incomplete clues and fragments, as well as on the ability of the viewer to meet the artist halfway. That's what makes the art bigger. (It never occurred to John Lennon that "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" suggested LSD, but once the work of art left his control, the interpretations of the audience made it something bigger than his intent.)

I think Oldenburg's suggestions of cows in that landscape is just about the bare minimum, but they're all that I need for the concept and I actually like them much better than many carefully drawn cows I've seen.

Drawings going after gesture and movement naturally want to extend beyond accurate borders and reveal relationships which often remain dead or unobserved in drawings pursuing some other authenticity. Going for gesture in drawing is a good place to learn about relational forces.

As so-called "Modern Art" began "eroding" prior artistic values during the 20th century, a cadre of teachers at the Art Students League made a point of discussing the long-understood relationship of poetics and integrity with their students.

An aphorism of that vital teaching moment survived: "It is one thing to get the energy in your work, but can you justify it?"

There's the rub. Saying something worth saying, articulately, and with energy in a perfectly plastic medium is no mean task. Rather, it is one of the ultimate challenges in all of the Arts. So much easier to deal with one mode only and not the other: to either get lost in the emotional splash of gesture, or become fixated on the technical-intellectual problems of reference and rendering. So much harder, by orders of magnitude, to mount the dragon of synthesizing the two; as much a problem of self-engineering as art engineering.

The great difficulty of meeting this challenge and successfully justifying gesture and graphic energy with objective information is hardly an artistic mandate to abandon justification altogether.

That's like saying; "Since it is so difficult to cook Beef Bourguignon well, it should be served uncooked." (Just the kind of unbaked cultural declaration one gets from sassy 60s sensationalists. Their dustbin awaits.)

The celebration of a thing half done is the victory of ADD ethics (a milieu where every petulant posture is really a desperate psychological ploy to keep hidden an inability to concentrate; the resulting values vacuum inevitably recoined the "New Values" and the resultant gibberish the "New Poety.")

Wes-- I like "man carrying a large parcel" too. It is a highly unorthodox selection of choices, and I don't think anyone could say they are choices dictated by an inability to draw. (Well, actually there's no telling what people around here could say...)

Kev Ferrara-- I think we agree that a common affliction of today's art world is that "they're word people who can't even understand visual aesthetics." That's a serious problem, but I don't think it's a problem for Oldenburg, whose drawings-- lush, impetuous, frisky, irreverent things that they are-- are mainly from the 1950s and 60s before the sickness of words afflicted much of art.

I don't think these drawings have anything to do with "memorializing infighting among petulant midcentury culturistas," I think they have to do with observing unobserved things in neglected places. I think they have to do with not caring one bit about the subjects that have traditionally brought wealth and fame to artists. I think they have the same playfulness that I admire in Dubuffet and Steinberg (the opposite of the pretentiousness that runs through much of the word art).

As for what's "worth filling up permanent public space," remember I am only talking here about his drawings, and I said, "I agree with art professor David Pagel who observed that 'More often than not, [Oldenburg's] preposterous proposals were primarily great excuses to make great drawings.'" I think I could support using public funds to construct one of his monuments just because they challenge our priorities, but I think the joke wears thin after that.

Sean Farrell-- Thanks for a most articulate contribution. I very much like the light you shed on the dancers and the landscapes. It helps me see what I intuitively like about these.

You write, "Beneath such arguments lives a desire for the self to reign supreme and in order to succeed it has to kill conscience and eventually impulse control." I understand the point, but it seems to me there's an additional complexity here.

Many of the artists I admire simulate the death of conscience and impulse control because that's the effect they're after. But they have learned through hard experience over the years that it takes a great deal of practice and knowledge to achieve that result. Artists such as George Booth or William Steig or John Cuneo, who sometimes aspire to distort their subjects with a child-like, uneven scrawl, go back again and again, re-drawing an image or cutting and pasting successful fragments from different drafts to get the effect they want. Their work takes discipline which seems antithetical to the illusion they want. When Bernie Fuchs went from painting tightly controlled, highly literal car illustrations to painting (what was at that time) wild, violent images he said the most difficult part was learning to "control looseness."

So many of the artists who genuinely don't care about "conscience" or "impulse control" just make a mess. Personally, when I look at pictures the difference seems clear as day to me; it couldn't be more obvious which artists have paid their dues and are trying to kill impulse control honestly, and which are just lazy slobs. I think many of the commenters here bristle at the latter category, and I agree with them. But I put Oldenburg in the former category.

David, sorry I didn’t make myself clear and I do appreciate your point about experimentation and controlling looseness etc. It’s a very good point. Yes students went to school with preconceived ideas and most really knew very little if anything.

I was referring to the crowd Kev was addressing who were using art as a political weapon or ideology for personal advantage. There were a lot of them in art schools as well as real artists. As a young student their mockery of the unwashed didn’t land well knowing I was taking the train home to sleep in a house paid for by the people they were referring. Many mothers in that time still sewed their own clothes and for their kids before getting their degrees and entering the work force. People had a real relationship with reality, things and objects back then. Thanks for your comments.

David and All,

Is there a good/best resource for discussion and analysis of art that appears unfinished (for any reason -- good, bad, phony pretentious, etc.)? I often find "unfinished" works more interesting to finished works as art, but its not clear to me when and why. These Oldenburg pieces seems mostly doodles to my untrained eye, so the discussion here has been illuminating. But the one I do like is the most finished piece - the man with the parcel, but even here, the image is mostly a sketch. What accounts for the power of unfinished images -- where one is aware that the image is just art, and not an intended depiction of some reality? For example, I enjoy the trompe l'oeil painting of Peto more than Harnett, though the latter is usually considered the superior artist in this genre. Harnett's painting are beautiful and emotionally powerful, but Peto's often appear more abandoned, half-intended, more tonalist and ambiguous -- at times appear unfinished. They "seem" more resonant in this genre precisely because they seem unfinished. Does that make sense? I'm curious if the "better" intention of artistic unfinishedness was corrupted by the 20th century nonsense that is so often discussed here. Is there a more noble use of unfinishedness in art (musical fragments, doodles, abandonded landscapes, etc) than would be expected? Even accidental unfinishedness seems more interesting e.g, Athenaeum portrait, Venus de Milo, some Pinkham paintings. How does that come about?

Kev, thanks for thoughtful comments.

I’m not saying that a painting isn’t a more complex undertaking than a pencil drawing, or a gesture drawing isn’t different than a study or one part of a complex composition on multiple levels.

David asked if anyone could add to why he liked the drawings. I looked closely at the drawings and could see the line was being used according to the subject and its movements as I described. It’s not something achieved through indifference whether the line is drawn quickly or slowly.

My point about gesture drawings wasn’t to encourage indifferent energy. For example, the rhythms of anatomy aren’t visible in a medical image, but start talking their own language once they start moving with the whole figure. Forces of rhythm start interacting in ways that align with other forces of drawing, large to small, dark to light, line weight,varying speed, overlapping, line sensitivity and various accents. Gesture drawings can be done with a felt force or a delicate line. A gesture can be powerful in an intimate way, the half drop of a head to a side, a shift of the eyes or slight forward movement of a shoulder. Discoveries reveal themselves in a never ending variety of ways. Gesture drawing in art school was about a figure leaning into a hip. It meant drawing quickly to get something for a one of two minute pose and was barely a subject. That’s not what I was referring to.

But to trash a drawing because it’s not part of a larger work isn’t for me though I agree your subject of more complex narrative pieces is neglected. Still, if one draws out of their head, go at it and show us what’s inside. If there’s a model, the same. There are many artists who can kill it with photo reference and even have a vision, but who have much less in their own hands. I looked at the three drawings and saw something that showed an understanding of line that was too developed to be pulled out of a hat.

I know Kev Ferrara (above) insists on "the essential similarity of the human perceptual basis" and the universality of aesthetic apprehension, but I think these strong views of great artists lets a little daylight in, and encourages the rest of us to look at the gods of art with a closer eye.

You are skewering me, my dear gentle fellow, with your own incorrect interpretation of my point.

I specifically referenced the basics of aesthetic feeling being universal. That's the old, even ancient, claim, what my research has long led me to (if that matters to anyone), and what the latest science has caught up to.

Literary work cannot utilize the same primal ground of direct intuitable effects of suggestive and significant form (which straightforwardly affect the imaginative intuition) as Art. For even to feel the rhythm of a sentence requires its words first be decoded and then sung in the mind's ear.

Writing is mostly predetermined as to form; a ready made symbolic lexicon and grammar that one must be trained in to comprehend, written in one typeface, in linear sequence all the way through, tribal (in the sense of requiring a great deal of culturally specific information and references to understand), and almost wholly pre-determined as to most of its form at all scales.

Which is to say, regarding that last point, a book's gotta look like a book, a chapter like a chapter, a page like a page, a paragraph like a paragraph, a sentence like a sentence, a clause like a clause, a word like a word; all through.

Whereas, as one Brandywine student put it about Pyle's compositional teaching, "Sooner or later one realized that the idea itself formed the basis of the design." That's a level of plasticity that cannot be coded for. It can only be sensed. Thus it is truly aesthetic by nature. Thus universal.

David wrote,

"As for what's "worth filling up permanent public space," remember I am only talking here about his drawings(...)"

I had thought these previous comments of yours told otherwise...

"His monuments to a cigarette butt or lipstick were a way of flipping off the art critics, wealthy collectors, gallery owners and museum curators who took themselves SO seriously. Those groups also turned up their noses at illustration and comic art, so you can hardly expect me to fault Oldenburg for irreverence."

"As long as the drawing is good, it doesn't bother me that Oldenburg offered a used cigarette butt as the subject for a monument."

We are in agreement that building out one of his jokes is fine. But creating an armada of giant cynical one-liners in the mode of Jeff Koons would be a negative act.

Just to be clear, I am not so much running broadsides against the drawings you have posted as the overpraise of them. As Chris Bennett has pointed out, many studio floors are littered with similarly unformed trifles. I'll cop to the same.

Although my versions of the "man under the weight of the heavy package" are thumbnail size. I was very surprised to hear Mr. Oldenburg's was so large, as there really isn't enough content there to warrant expansion. Which points to a pattern, where Mr. Oldenburg blows up trifles far beyond their merit, creating giant aesthetic vacuum balloons instead of works worthy of contemplation.

> I don't know if it affects your judgment, but these are not "tiny doodles," most of them are great big drawings

You buried the lede here! The drawings are worth contemplation if for nothing else than that he is doing the sort of mark making most artists do at 1” X 1” at an unfathomable 11” x 17”.

I’ll say this, while it doesn’t particularly make me want to look at them, it does make me want to go mess around in the studio which is certainly something

A large light doesn’t fight a lesser light because they’re made of the same stuff. A small observation of unity can be as poignant as a larger one as they serve the same unifying purpose.

The arguments between quantum and relativity prove but that these two haven’t found their unity possibly because they’re of different languages. Just as common sense shares the same reality but by itself has access to neither.

We started out thinking the computer was a convenience, but are suddenly told there isn’t the energy to run a computer world and are being asked to drop essential basics, like food and even money, a measure of trade and work. So in some sense the question is what is serving what?

Achievement is an accumulation of small bits of understanding (towards a deeper understanding) and each bit is a joy and as pleasant to learn from a teacher as if self observed because it’s in the understanding that each resonates, making sense. Seeking unity is a long and sometimes mysterious process. But an artist has to make many observations on their own before they gain the confidence to believe what they’re seeing with their own eyes and become their own person.

What Pyle’s student said above isn’t going away because it was there before he said it and it will find its way again. Irreverence is a strange theme after a lifetime of trying to achieve something but such is the nature of warring parties. Looking up from the underside of a piano in tribute to Milton Glaser and the underside of an ironing board from the late Mr. Oldenburg, I’m starting to get the sinking feeling that the unity in drawing may never be reconciled with unity in greater works of art on this venue.

Don't you think that pareidolia (nice word by the way) is a very different game when we look at a painting (which, by definition has some intent) than when we look at a cloud or a rock?

Yes, in that a work of plastic art utilises something of the pareidolia effect brush mark by brush mark to build illusions as a hierarchy of metaphorical meanings that stack up in relation to one another to communicate a grand sensual meaning experienced in the physical frame of the beholder.

So the meaninglessness of a work is in direct proportion to the lack of relation between its parts. As a consequence, in the case of these drawings which I consider to be very low on the meaningfulness scale, I think one is pretty much left only with playing the game of pareidolia pursuits you mentioned.

So much of art depends on the extent to which the artist makes that intent literal and explicit.

And you follow with:

So much of the quality of this type of art depends on the ability of the artist to suggest or imply meaning with incomplete clues and fragments, as well as on the ability of the viewer to meet the artist halfway.

These two propositions are in contradiction with one another other.

The first I believe to be completely false.

But the second I largely agree with except for your phrase "this type of art". I believe all art to be implicit in nature.

That's what makes the art bigger. (It never occurred to John Lennon that "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" suggested LSD, but once the work of art left his control, the interpretations of the audience made it something bigger than his intent.)

Bigger yes, more meaningful, definitely not. The psychedelic, mind-altered, out-of-one's-tree theme pervades the whole song, the words and musical structure embody it right from the get-go. The LSD thing was implicit all along, saying out loud is just a delightful wool-gathering observation post hoc.

I think Oldenburg's suggestions of cows in that landscape is just about the bare minimum, but they're all that I need for the concept....

But David, poetry, being a meta-language addressed to the feeling for the unknowable does not deal in concepts.

I agree that "only truth deserves credence" and as soon as you work that out with Pontius Pilate please report back to me.

Do you share wisdom you do not believe is true?

Wes-- I don't know of any books or online material devoted to "discussion and analysis of art that appears unfinished," although other here might. Usually the discussion of unfinished work shows up as a few paragraphs in a work devoted to larger subjects. But quite frankly, I think you're more likely to get a smart, practical and candid discussion of the subject from some of the brainiacs who comment here than from museum curators or PhD art scholars.

You write, "I'm curious if the 'better' intention of artistic unfinishedness was corrupted by the 20th century nonsense that is so often discussed here." Actually, my view is just the opposite-- that art over the past 150 years has distanced itself from the perfect glass-like finish of Bouguereau and Boris in favor of spontaneity, directness, simplicity, expressiveness and immediacy, all of which helped legitimize "unfinished" art and rescue art from becoming too mannered and stilted.

". . . you're more likely to get a smart, practical and candid discussion of the subject from some of the brainiacs who comment here than from museum curators or PhD art scholars."

Exactly! That's at least a big part of the value of your blog. Oh, and of course, the art.

thanks!

The whole concept of "unfinished art" is rather suspicious to me.

I was told once that I should finish my drawings (many years ago when I was silly enough to show them), and my gut reaction was to say "if you know what that does even mean, then finish them yourself".

Those were my drawings, and wether they were finished or not was only for me to decide, thank you very much. I took the critique as just passive-aggresive trolling.

(Of course they were actually unfinished because I knew my limitations and that had i kept working on them they would just get worse, but anyway, the principle stands)

Kev Ferrara wrote: "Do you share wisdom you do not believe is true?"

Returning to our science analogy, Niels Bohr wrote, "The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. The opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth." My point in citing Pilate was to suggest that your comment, "only truth deserves credence" begs the question, "whose truth?" a question over which people have been slaughtering each other since Biblical times. A little humility is warranted, please.

In my praise for Oldenburg's drawings (not actual physical monuments) I was trying to address his drawings of monuments, 95% of which were never constructed and (I believe) were never meant to be constructed. They were audacious concepts on paper, but who believes the city of Chicago would build a huge monument to smoke? Sorry if that wasn't clear. I would not waste public funds building more than one or at most two of his monuments.

chris bennett-- you write that my statement, "So much of art depends on the extent to which the artist makes that intent literal and explicit" is completely false.

That wasn't intended to be a controversial statement. Let me try again: I'm sure you don't believe that art should answer every question it raises. Just like arsenic, ambiguity is a stimulant in small doses but lethal in large doses. My point in saying that "So much of art depends on the extent to which the artist makes that intent literal and explicit" is that an artist can wreck a picture at either extreme on that sliding scale. Whether the artist spells out his or her intent too completely, or doesn't give the viewer enough clues, the inevitable result is an inferior picture. Finding the just the right sweet spot in the middle is one of the real tricks of getting a picture right.

Do you still think my point is completely false, or only partially false?

With respect to Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds, if "The LSD thing was implicit all along," Lennon swears that he never thought of it. After a point, when an artist lets go of a work it takes on a life and a meaning of its own. The artist no longer gets to control it.

Niels Bohr wrote, "The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. The opposite of a profound truth may well be another profound truth."

"May well" indeed. May well not also, one presumes from the construction.

Where does Bohr's equivocal hypothesis get us in the realm of Art? How is it a response to the question I asked?

Maybe you'll deign to offer an example of "two opposing truths" as it relates to the subject at hand? For example, which set of 'opposing truths' tell us that Mr. Oldenburg's work is not unfinished and vague? Or that it is 'great' for being so?

You are also encouraged to circle back to the question you sloughed off:

Do you share wisdom (with your children, say) you do not believe is true?

My point in citing Pilate was to suggest that your comment, "only truth deserves credence" begs the question, "whose truth?" a question over which people have been slaughtering each other since Biblical times.

Yes, that was obvious. That's been your go-to tactic on the question.

Also obvious is that you are confusing 'perspective' with truth. Perspectives naturally clash, truths naturally nest within each other, overlap or superpose without incident, or merge.

Why this conflation of perspective and truth ALWAYS happens when dealing with those indoctrinated into postmodernist sophistry is no mystery.

But this philosophical Street Joke, nonetheless, leads us into a multipolar trap. One that, writ large, sends us all to the hell of warfare, unreason, addiction, and savagery.

My Truth is that vandalism is industrious, so I'm going to destroy your house.

My Truth is one can be mature and still think and act like a bratty teen.

My Truth is that only laws I think are valid should be obeyed.

My Truth is that mimicry is originality, and stealing is creative.

My Truth is that if heroin makes me happy, then it is a good habit to have.

My Truth is that everything you say that I disagree with is an intentional lie.

And so on.

You speak of being humble. Sure.

But we must also not be hypocrites. And that will help us be humble in turn.

Since each of us acts on the basis of what we are forced to believe is true - since we are yoked to our unspoken embodied axioms - wholly internalized understandings based on our undeniable experiences with recurring phenomena - there is indeed no escape from that which is true.

Regardless of postmodernist cant.

____

Incidentally, trashing the linguistic turn in philosophy as a "gelding" mode of inquiry is no more an argument against their conclusions than Pomo's assertions are defeated by pointing out that several of its founding fathers were admitted pedophiles.

But doesn't this helps a little bit?

. . . "Pomo's assertions are defeated by pointing out that several of its founding fathers were admitted pedophiles."

Or is it a truth that ad hominen attacks are aways wrong? I try to remind people that Trump was well trained by Roy Cohn. And that is (or should be) "Nuff said".

"The whole concept of "unfinished art" is rather suspicious to me."

Nice story. I only meant apparent "unfinishedness" - not whether they should or not be finished - aLa Athenaeum portrait or incomplete -- like the Venus de Milo. These have a certain charm -- why?

After a point, when an artist lets go of a work it takes on a life and a meaning of its own. The artist no longer gets to control it.

Eh?

The artwork remains the artwork. Its effects are part of an aesthetic engine built by the artist to run into perpetuity. Interpretations come and go, only somewhat quicker than civilizations.

Most people who have heard Lucy In The Sky with Diamonds probably don't know the LSD interpretation. They do know that Lucy in the Sky sounds otherworldly and strange, because they've experienced it.

For the first 30 or so years that that song was in my life I'd never heard the LSD interpretation. And since I've never taken LSD, the interpretation was mostly meaningless to me anyhow, except insofar as I already recognized that the song sounds otherworldly and strange and I've heard enough stories about hallucinogenic use to put the connection.

Since it is now becoming more widely known via the internet that Lennon never intended that interpretation, only the most stubborn passengers on the LSD train would still insist on it.

I happen to have heard Lucy In The Sky on the radio last week. It sounded otherworldly and strange. Same as it ever was.

I'm sure you don't believe that art should answer every question it raises.

Well, I can't say I believe that a work of art asks any questions. I mean, what questions does Constable's Hay Wain or Whistler's Mother ask? OK, someone might say, "doesn't The Mona Lisa make us ask why she's smiling?" But this is not a question asked by the work itself but by the person looking at it. They may as well ask if the hay wagon was stuck in the river or if Mrs Whistler's son liked her... or any question whatsoever that floats into one's mind when happening to look at anything at all. To put it in technical terms, a work of art cannot be paraphrased.

My point in saying that "So much of art depends on the extent to which the artist makes that intent literal and explicit" is that an artist can wreck a picture at either extreme on that sliding scale. Whether the artist spells out his or her intent too completely, or doesn't give the viewer enough clues, the inevitable result is an inferior picture. Finding the just the right sweet spot in the middle is one of the real tricks of getting a picture right.

Do you still think my point is completely false, or only partially false?

I'm afraid so David, because of the nature of what you are applying it to. The artist's intent does not start with the surface language they employ, because the surface language is only the conveyor of meaning, not the meaning itself. Failing to realize this is why so many inexperienced painters fixate on style rather than trying to discover (non-verbally and by participation in their craft) what they are try to 'say' and then developing a paint handling language to communicate it fluently and directly.

So any idea of there being such a thing as a 'sweet spot' between, let's say, implicit and explicit, chaos and order, lost and found, messy and neat, mystery and clue is to believe that intent is governed by its realization (surface appearance) rather than the other way around.

A way of exampling what I mean is to think of the early and late Pietas of Michelangelo; the Vatican and the Rondanini. The former is clear and polished, the latter is half-formed and rough, and its meaning seems dependent on the shape it was before revision. Both are sublime and breathtakingly beautiful to behold, yet if Michelangelo had continued to live he would have pressed on with the Rondanini towards clearer realization. So how does any notion of a sweet-spot between the two poles you mention apply?

With respect to Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds, if "The LSD thing was implicit all along," Lennon swears that he never thought of it.

I understood that. I think you should, if you care to, read my answer to this a little more closely.

...when an artist lets go of a work it takes on a life and a meaning of its own. The artist no longer gets to control it.

The life and meaning authored into the work remains locked into it, unchanged. The interpretations, deconstructions, cultural framings and historical context revisions of bottle-lensed critics and all whom they influence are no more than the barnacles under the hull of a great ship.

chris bennett and kev ferrara-- you both object to my point that "when an artist lets go of a work it takes on a life and a meaning of its own. The artist no longer gets to control it."

When Kev objected I assumed he was just being his normal contrarian self. After all, he'd just gotten through saying, "as was understood since antiquity, the thing speaks for itself. Even if it mumbles," so how could he possibly claim that an artist continues to speak for a finished work of art? In fact, Kev has always railed against artists who prop up their art with long windy explanations of their underlying intentions, and I've agreed with him on that. But when chris also chimed in that an artist's meaning controls the work forever and that viewers are "barnacles under the hull of a great ship," I thought maybe kev wasn't just being disputatious to be difficult. Perhaps we need to revisit what I assumed was well trod ground.

There are two points to make here. The first (which I assumed everyone understood) is that an artist has to let go because no matter how noble or profound his or her intentions, an art object has to stand or fall on its own. It either communicates or it doesn't. The viewer in the gallery should be under no obligation to read an artist's manifesto or research their personal history before viewing a picture. In my experience the viewers who try the hardest often have the most tiresome, narrow reactions to art.

Artists don't always understand consciously why they do everything they do, and even if they did, artists die and their explanations are erased by the wind; when an artist is no longer around to argue on behalf of their picture, art must be able to stand alone and account for itself to the viewer in the museum. The artist has no permanent choke hold on the meaning of his or her art and that's usually a good thing.

Matisse said that artists should have their tongues cut out before they start explaining their work.

This brings me to the second point: art which presumes to answer every question is usually inferior art. Art's questions may be constant and eternal, but the answers change over time, at least in living, breathing art. Chris writes, "The life and meaning authored into the work remains locked into it, unchanged." By that standard, Beethoven's second symphony might be eternally about his gastric distress, a musical rendition of his hiccups, belches and flatulence during a period of emotional agitation. But fortunately, the music remains with us as a thing of beauty.

I think art forms the strongest connection with viewers when it doesn't presume to answer every question, and it leaves room for curious minds to personalize the artistic experience and flesh out the meaning with the background they bring to the picture. If Kev can tolerate one more analogy to science, I suggested the following in a post long ago:

"Chemistry tells us that the strongest bond between two substances is formed when their molecular structures are not too complete, and thus they are receptive to sharing pairs of electrons between them. A substance with gaps in its electrons can fill those gaps with the electrons of another substance. In this way, two molecules can unite into one bigger molecule-- a connection called a covalent bond, heavily crosslinked and powerful in a way no mere glue can match. (This is why epoxy, which combines the electrons of two ingredients, is so much stronger than regular glue applied unilaterally to a surface.)

No matter how much scientific data we compile to understand and capture an art object, we will never bond with it the way we might if we kept our outer electron ring open and receptive. If we come to art fortified with too much information, we have fewer free electrons available for the new combinations that make so much of art worthwhile."

(For anyone who cares, this is from: https://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2012/12/against-scholarship-in-arts.html )

After all, he'd just gotten through saying, "as was understood since antiquity, the thing speaks for itself. Even if it mumbles," so how could he possibly claim that an artist continues to speak for a finished work of art?

The problem is not that I am contrarian, or argumentative my good fellow. And I certainly haven't contradicted myself, as you have accused me of doing.

Rather, it is apparent that you are simply unable to understand me. And, one presumes, you are absolutely sure the problem is on my end and not yours. (It is worth considering that you just might be wrong on that count.)

Re-explained, re-integrated, for the twentieth time:

A work of art is a work of engineering. Composition was often called an 'engine' by practitioners in the 19th century. The aesthetic engine of an artwork only needs an eye to run and a brain to receive the data.

When the eye runs the artistic engine, the engine actually runs the eye. Like the needle on the record, the needle inserts into the groove, but the groove is what vibrates the needle and sends the complex signals back through the sensory apparatus. We are told that we 'play' records, but the reverse is obviously the truth.

As the eye and the compositional engine interact, the eye is taken through a densely multilayered and multidirectional journey of colors and tensions and contrasts, etc.

In the process of playing the artograph with our eye, the engine "says" (expresses via sensual symbolism through plastic form and effect) what it has been composed to "say" back through the needle of the eye.

A compositional engine does not "say" in a way that makes its message readily translatable into words. As Dean Cornwell said, if I may repeat the key truth once more with feeling, "Art is a language separate and distinct from literature."

Aesthetic communication has no verbal corollary. No surface corollary either. That's why its so difficult to grok for the uninitiated. "Composition is the thing that haunts," remarked N.C. Wyeth once upon a time. Indeed, it haunts because it has symbolized itself in its own language. And if one can't experience that language on its own terms, there are no other terms.

Since an artistic engine only needs an eye to run, the work - any artwork - only needs a single human for the artist to "speak" again anew.

In fact, so long as the art exists, and people are still people with eyeballs, the work will 'speak' into perpetuity by the force of the aesthetic messages engineered as the work. This is the sense in which one understands that the artist will continue to speak through the work.

The chatty "sophisticated" folk who encounter the work - who may or may not be able to connect at the aesthetic level with the work, or who may or may not have a conscious mind that is actually hooked up to their intuition, or who simply can't shut up the voices in their heads - they can get taken away (after the initial aesthetic effect has worn off) by whatever fancies and fantasies, by whatever art theories, philosophical mumbo jumbo, or critical theory bullshit they wish.

It doesn't matter.

All the talk will fall away with the fallen vigor of the talkers; in good time. Meanwhile the aesthetic engine remains the same for as long as the work exists. And thus its song remains the same into perpetuity, regardless of interpretation.

Chris writes, "The life and meaning authored into the work remains locked into it, unchanged." By that standard, Beethoven's second symphony might be eternally about his gastric distress, a musical rendition of his hiccups, belches and flatulence during a period of emotional agitation.

David, I'm disappointed. Why you should draw this idiotic conclusion from my statement given what I've been trying, in good faith to carefully explain, is beyond silly. And further to this, rather than address the specifics of my challenges to your claims you just hop back to restating them. Consequently, there's little point in my replying further. That said, thank you for the discussion, such as it was.

PS: Just noticed Kev's reply above that was posted as I was typing mine. He certainly isn't a contrarian or argumentative, but he certainly has patience and a lot of stamina! His eye's needle playing the artograph is a beautiful metaphor/analogy for the aesthetic mechanism that is created when an artist authors a work. My thanks to him for taking the trouble to lay out again, for the umpteenth time, the core understanding being discussed here.

No more big hamburgers. Where's the beef?

Post a Comment