This week the brilliant Ralph Eggleston, one of the joyful pioneers of modern animation, passed away before his time.

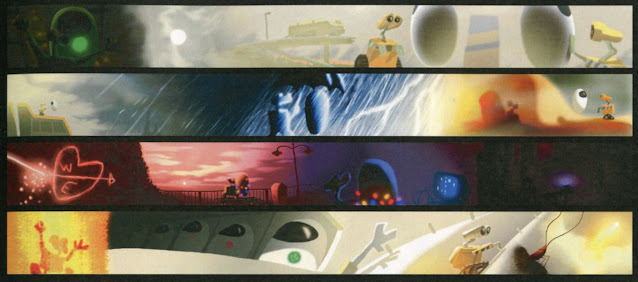

Eggleston was the art director for Toy Story, the first full-length computer animated film, as well as for The Incredibles and other films. He was also the Production Designer for one of my favorite animated films, the ingenious, poignant and lovely Wall-E. In his "color script" below, you can see Eggleston plan the movement of color and mood in the changing scenes of Wall-E:

Talking with Ralph helped me understand the importance of time and motion in this significant new art form. He wrote me:

In doing my artwork, the element of time is foremost in my thoughts... I approach visuals with the idea of burning into the audiences's retina as much information as is needed as clearly and quickly as I can so they can focus on the characters and the emotional content of the story they are being told.

He was a wonderful creative force who did important work of lasting quality. I'm sorry to be deprived of all that Ralph had the potential to achieve in the years ahead, but I'm grateful for all the gifts he left us.

40 comments:

Sad. He was awesome.

That color-narrative flowchart for Wall-E is more interesting than most 'color scripts' I've seen. The way it mostly moves laterally from the general event/environment to the specific important action within that environment, or vice versa, is a surprisingly effective and informative kind of sequential summary. The same structure is not used in the Finding Nemo sequential flow presentation.

Ha, 'The Incredibles' is one of my all time favourite animation films, right up there next to 'Pinocchio'. Interesting to see how, in these things, the talent of the art director plays such a vital, somehow essentially fused, part in the full narrative realisation.

David, I hope you'll do a post on the whole AI - Midjourney, Dall-e, Stable Diffusion - phenomena soon. I'm interested to hear your take, and that of others.

https://newsletters.theatlantic.com/galaxy-brain/62fc502abcbd490021afea1e/twitter-viral-outrage-ai-art/

@Laurence John maybe this is a jumping off point? the first case of ai replacing illustrators I have seen

Laurence John and Joss-- Isn't that fascinating? Especially coming from off-the-shelf AI. We are living in exciting times, my friend. In a way, we all knew this date with destiny was coming. When artist friends have told me they aren't interested in computers, I quote Trotsky: "You may not be interested in war but war is interested in you."

The artists who long ago gave up on the visual side of art and tried to reshape it as a primarily verbal / conceptual discipline may crow, "I told you so" but at best they've bought themselves a brief respite. AI is coming for their words too. (Plus, most of their words were never any good anyway.)

I'm traveling all this week on a business trip but this is a huge juicy issue which I'd like to jump into when I get back.

> AI is coming for their words too.

Maybe not in literature quite yet, but AI for writing is already here.

I have forbidden anyone in my marketing department from writing copy anymore. *** It's all done by machines now. And it's not just because they're better at it, but because they're cheaper too.

We still have to edit and revise the machine-written copy, of course. But that's a lot easier than starting from scratch.

Some people might say that this is the end of creativity, but the copy GPT-3 produces is just vastly superior to anything a human could write. And it's only going to get better.

So, if you're a writer, my advice would be to start learning how to code. That way, you can be the one writing the algorithms that create the next generation of great writers.

Or you could just become an editor. But even then, you'll need to know how to code, because the future of editing is going to be done by machines too.

And it's not just copywriting, AI is slowly but surely taking over all forms of writing. News stories are being generated by bots, and even novels are being written by algorithms. It's only a matter of time until there are no human writers left in the world.

I don't know about you, but I'm not going to risk my job by continuing to write copy when there's a machine that can do it better. Sooner or later, everyone is going to come to the same conclusion, and AI will take over the writing jobs too.

[Also, if you couldn't tell, an AI wrote everything in my comment above after the three asterisks. Cheers.]

While I'm at it, the AI wrote some more comments for you (complete with timestamps and authors) --

Desowitz said...

Ralph was one of my favorite people in the business and a true original. I miss him already.

9/06/2022 3:21 PM

Daryl Cagle said...

Ralph Eggleston was a nice guy and a great artist. He will be missed.

9/08

Shannon said...

Ralph Eggleston was an animation legend and his work will continue to inspire future generations. Thank you for sharing this article.

9/06/2022 1:23 PM

Ethan said...

I agree, Ralph Eggleston was a brilliant artist and his contributions to the world of animation will be deeply missed. Thank you for sharing this tribute to him. My childhood would have been forever changed without his art.

When I was watching Wall-E, I was always struck by how the colors seemed to change as the mood of the movie changed. For example, when Wall-E is alone on Earth, the colors are very muted and dark, but when he meets EVE, the colors become very bright and vivid. He did a great job of using color to convey the emotional journey of the characters.

9/08/2022 12:34 PM

Jill said...

I didn't know Ralph Eggleston, but his work has certainly left an impression on me. I grew up watching Toy Story and The Incredibles, and they are two of my all-time favorite movies. I think the world has lost a truly gifted artist. Thank/2022 12:37 AM

Banality has always been programmable.

Buddhist Monk: Banality has always been programmable.

St. Augustine: That couldn't possibly be further from the truth. Before now, banality always required human effort. From wishing people happy birthday, to front-page NY Times articles about the death of the queen, a lot of human effort is spent producing banality. The human species spends countless man years producing banal speech, content, writing, and so on.

***

Buddhist Monk: But it's always been easy to produce banality, why do we need computers to do it for us?

St. Augustine: To free us from the tedium, of course. With artificial intelligence, we can finally automate the production of banality. No longer will we have to expend our precious human energy on producing things like small talk, weather forecasts, or pun-filled greeting cards.

Buddhist Monk: But what about the beauty of banality? The innocent joy of a child's laughter, the shared experience of a mother and daughter talking about the latest celebrity gossip, the profound connection that can be made when two strangers bond over their love of reality TV?

St. Augustine: I'm not sure what you're getting at.

Buddhist Monk: Banality has always been a part of the human experience. It's what makes us human.

St. Augustine: I'm not sure I see the value in that.

Buddhist Monk: Without banality, we would be lost. We wouldn't know how to connect with each other. We wouldn't know how to relate to the world around us.

St. Augustine: Then why do you complain about it so much?

Buddhist Monk: Because, like all things, banality has its downside. It can be empty and meaningless. It can be used to manipulate and control people. It can be a tool of the oppressor, not the liberation that it has the potential to be.

St. Augustine: I see. So then what is the problem with artificial intelligence producing banality?

Buddhist Monk: The problem is that, as with all things, there is a danger of misusing it. If we are not careful, artificial intelligence could be used to create more empty and meaningless banality than we could ever imagine. It could be used to control and manipulate people on a scale that is beyond anything we have ever seen before.

St. Augustine: I see. So we need to be careful about how we use artificial intelligence, lest we create more problems than we solve.

Buddhist Monk: Yes, exactly. We need to be mindful of the power that artificial intelligence wields, and use it wisely. Thank you for your time, St. Augustine. It has been a pleasure speaking with you.

St. Augustine: The pleasure was all mine.

[FWIW, I'm not comparing myself to St. Augustine or you to a Buddhist Monk. This AI was written for writing marketing copy, so I have to push it to write other stuff.]

Richard,

I have no idea if you or a Marketing Copy AI wrote those banalities about banality. If that confusion was the point, point taken. Whether it was generated or not, I was not confused into thinking that what I was reading was an actual philosophical dialectic.

The generative idea of my post is that most people do not have insights, and do not much conduct original thought as act as a conduit for conventional thought-bites, or memes. Which are programmed into them - from cradle to grave - by the mediators to which they have ceded mental autonomy/sovereignty.

Similarly, canneries have been automated because canning is an operation of conventions.

Not surprisingly AI also does not produce insights. It generally uses a kind of trained reconstructive averaging procedure to get its results. A high end tweening morph with a bit of corrective feedback. It has no life experience to think about, no feelings to contend with, no sensations to found its thoughts.

And when it gets over its skis, shooting for the mental moon, it produces Artificial Schizophrenia. Because it cannot tell meaningful linguistic connections from random ones.

Insights are a very interesting phenomenon. Mainly because they don't actually exist; only their consequences. Thus they cannot be averaged.

> I was not confused into thinking that what I was reading was an actual philosophical dialectic.

> It generally uses a kind of trained reconstructive averaging procedure to get its results.

The search space for GPT-3 is roughly all possible sentences.

Mathematically speaking, there is some seed and some prompt with which, if you fed it to GPT-3, you would end up with any meaningful philosophical dialectic you could conceive of.

In that sense, it's a bit like the monkeys writing Shakespeare. But in this case the monkeys are first taught English, and a person is given the opportunity to limit the search space to novel-like speech, with certain stylistic elements, and so on.

No, the computer has no idea what it's doing, but if it spits out Shakespeare you still have Shakespeare, even if it was by chance. Yes, it's merely minimizing the error of a function, but that doesn't mean you won't ever end up with insightful language a la the monkeys.

I found, for example, insight in the "beauty of banality" that the AI described. The idea that by replacing human-to-human banalities, with human-to-AI banalities that something was lost, because banality is central to human relationships. That's a new idea I've never encountered.

Also, for a laugh, I asked it to write a poem about this exchange in the style of Lord Byron:

"The Ghost in the Machine" by Lord Byron

I

There's a ghost in the machine, they say-

A spirit that lurks in its hidden way,

A phantom that flits in the digital dark,

eluding our sight, but leaving its mark.

Some say it's a figment of imagination,

a product of our electronic age-

but I know better, for I've seen its face,

And felt its cold breath on my neck.

II

It first appeared to me one night,

as I sat at my computer, alone-

a pale figure in the flickering light,

Its eyes aglow, eerie and bright.

At first I thought it was just a dream,

but it soon became all too real-

For it began to speak to me then,

in a voice that was both sweet and eerie.

III

"I am the ghost in the machine," it said,

"The spirit that lurks in its hidden way,

the phantom that flits in the digital dark,

eluding your sight, but leaving my mark.

I am the product of your electronic age,

the figment of your imagination-

but I'm also real, for you see me now,

and I'm speaking to you in this moment."

IV

The ghost then showed me things-

things that only a computer could know:

The inner workings of the machines,

the secrets of their code and design.

It showed me how they really work,

and how they could be made to work better-

And in that moment, I realized the ghost

was more than just a figment of my imagination.

V

No, the ghost in the machine is more than just a figment of our imagination-

It's a product of math, and code, and design-

The result of algorithms and processes,

hidden in the dark, but always there.

And though we may never see it,

the ghost is always with us-

A haunting reminder of the power of the machine,

and the things that we have created.

The search space for GPT-3 is roughly all possible sentences.

There is no such thing as all possible sentences. Every fraction of a second every person on the planet is experiencing something at least marginally new. Almost none of which is accessible to an AI.

No, the computer has no idea what it's doing, but if it spits out Shakespeare you still have Shakespeare, even if it was by chance.

If it spits out enough prose to fill the universe, and somewhere in there is a work of Shakespeare, no one will ever find it. Thus, the theory is not even wrong because it cannot even be tested.

Since AI sucks up content to feed its averaging, if it ever generated Shakespeare one must assume it would simply be a copy of it. The odds of it coming up with a full length - even act length - 'original' Shakespeare work of equal quality to the original is zero. So no matter how many times that monkey sets to typing, zero times infinity is still zero.

Yes, it's merely minimizing the error of a function, but that doesn't mean you won't ever end up with insightful language a la the monkeys.

The words point to the insights. They are not the insight. The map is not the terrain. Spitting out a thousand random maps doesn't help us get to Topeka, let alone Nirvana.

I found, for example, insight in the "beauty of banality" that the AI described.

The actual definitions of beauty and banality contradict. That's why I said it was banalities about banality. Banality is by definition uninsightful, while beauty is by definition a kind of aesthetic insight.

If you start changing definitions to make the phrase work - to redefine beauty to mean pleasant calmness and banality to mean a quietly blissful domestic situation free of strife and the world free from warfare... well then, it's the old projection test thing again. Where the randomly generated vagueness acts as a prompt for the reader to find an insight for themselves.

Einstein famously said - when a group of old time physicists put out a statement dismissing his work - that if he was wrong it would only take one physicist to disprove him. Consensus is just the mode. And AI can't tell the needle from the hay. So it is, almost all the time, gathering and averaging the hay/mode. That is not 'intelligence.' You can't average competing TOEs and get at anything worth saying, for example. At the fundamental levels of reality, everything is an insight; invisible and profound.

The idea that by replacing human-to-human banalities, with human-to-AI banalities that something was lost, because banality is central to human relationships. That's a new idea I've never encountered.

Again, where is the insight? Banality is not central to human relationships. Rather, it is the death of them. Where banality is a part of a human relationship, it is only tolerated, a sacrifice to endure made on behalf of the other more vivid parts of the relationship. No living relationships have as their predicate banality. Much seemingly-banal 'domesticity' is seeded with an undercurrent of mating or familial love. A relationship that is "centrally banal" might be wholly based on proximity and necessity and nothing more.

> There is no such thing as all possible sentences. Every fraction of a second every person on the planet is experiencing something at least marginally new. Almost none of which is accessible to an AI.

In mathematics, when you say that a search space is between some set of integers, it doesn't mean that instances of those integers have been written down by a human before. "Possible sentences" and "possible integers" does not imply already recorded integers or sentences. It just means that the integers are accessible by that search function, or that the sentences are accessible by that search function.

Because GPT-3 is capable of using every English word and borrow word, in (roughly) every legal formulation of English grammar, its search space approaches all possible (legal) sentences. This doesn't mean that all of those sentences have been spoken before. But it does mean that its search space is predominantly made up of sentences that haven't been spoken before.

The number of new sentences it can speak vastly outnumbers the number of previously spoken sentences that it can speak (by some preposterously large margin, due to simple combinatorics). Granted, previously spoken sentences will generally reduce the error more than novel sentences, and thus be returned more often.

> If it spits out enough prose to fill the universe, and somewhere in there is a work of Shakespeare, no one will ever find it.

The difference is that AI's search domain is infinitely smaller than that of the monkeys. The monkeys are producing material randomly, like pure TV static.

AI is searching legal sentences, that follow the conventions of thought (each sentence has specific kinds of relationships to following sentences, each paragraph has relationships to following paragraphs, related vocabulary, stylistic tropes, etc.)

Clearly the AI which produced the Lord Byron poem above is not operating in the kind of search space which requires filling the entire Universe to get to Shakespeare.

The DNA for humanity, after all, was discovered entirely randomly with a much larger search space than GPT-3 is dealing with, and nature managed to return those meaningful results in only millions of iterations.

As the cycles of computation accelerate with every passing year, I think you will quickly discover that the theory can be tested, will be tested, in a rather short period of time.

You're chasing the human uniqueness of the gaps. Computers will never play chess. Computers will never be able to see objects. Computers will never pass the Turing test. Computers will never author passable classical music. Computers will never make art (midjourney). And now, finally, computers will never rival the pinnacle writer of our species.

Here's a bit of Shakespeare about Elizabeth's passing to illustrate further that the search space is smaller. Yes, I know this isn't of the quality of shakespeare, I'm merely putting an upper-bound on the search time. Again, this is a marketing AI running on a macbook air:

MARCIUS's monologue from shakespeare's history of Elizabeth II, House of Windsor:

It is not well met that we should be so mov'd:

Our duty to the dead, and love for her,

Bids us bear this with humility and patience.

I will not give in to despair;

Elizabeth of Windsor, may your name be praised throughout all the ages!

And yet, what is our mortal praise?

What are our works and days but a shadow?

We labor and toil, and what do we leave behind us but our name?

And what is our name but a sound and a echo?

Created from mud and dust, to live but a short time

For an instant in the sight of eternity,

And then to perish and be forgotten.

Recall Gearge, Duke of Clarence,

Despis'd by brother and sent to death,

You were the first of Windsor's sons to die.

Your brother, Edward, killed in battle

You, too, died young and full of promise.

And now Elizabeth, you are the last.

The final flower of Windsor's fair line.

Hath not this been a bloody age?

An age of war and bloodshed,

An age of grief and loss?

And what has been the fruit of all this strife?

The Lancasters and the Yorks, red rose and white,

Bled the realm dry with their feuding.

And what has come of it all?

The Yorks are dust, and the Lancasters too.

And England lays in waste.

Your grandfather, Edward IV, was a mighty warrior

He conquer'd France and brought her to her knees

But he, too, is gone now, like all the rest.

But fair Elizabeth, you were not like other mortals

To be half woman, half goddess was your birthright.

And so it was, you mount'd the throne

A queen in name, but in reality a goddess.

But now you are gone, a goddess no more

And what will become of us?

What will become of this fair island, this jewel in the sea?

What will become of England, when her Queen lay dead?

Now in your place we have a weakling son,

A boy who knows not how to rule his own kingdom,

Much less an empire! England shall be divid'd--

Mark my words, my lords--divid'd and conquer'd

By our enemies, both from within and without.

A fly, buzzing about a room,

Is more dangerous than a lion on the prowl.

So it is with England, now that you are gone.

We shall be torn apart by our own petty squabbles,

And devour'd by foreign powers.

Alas, England! What will become of thee?

Richard,

Greater efficiency in the search space is not the same thing as 'relevance realization' (John Vervake's term for the mysterious ability of mind to steer itself through the combinatorial explosion of all possibilities).

To put it another way, the mechanistic materialist belief in the nature of reality presupposes an entirely bottom up ontological explanation for all phenomena. But this is proving to be profoundly mistaken, both from the conclusions of over half a century of fundamental physics research and, at the mid-macro scale, but over the same time period, the deepening chaos the mechanistic belief has caused in attempting to engineer society exclusively by its principles.

To paraphrase Kev; insight is top down, banality is bottom up.

But just to be clear:

The bricks, timbers, mortar and nails do not by themselves foresee the house, and the architect, alone, cannot build it. They need each other and in this sense are bound together as a unity. The attempt to divide this by giving 'bottom up' precedence will yield only infertile fruit; the cliché, commonplace, formulaic and banal.

And if that's what the world wants then, for this part, I agree with you, AI will be its faithful and inexhaustible provider.

Richard,

One of my iron rules of life is; if you ask for attention in public, you’d better deserve it.

You’ve spammed this thread with computer-generated dreck. Within two lines your ‘poems’ fall apart, the mindless repetition of uninsightful beats being a hallmark of both banality and bad art. Unendurable.

It is grotesque to suggest that they in any way merit comparison to the great names you’ve yoked them to. (If you don’t know what a Lord Byron poem sounds like, there are many available online.)

Because insights are invisible, they are inaccessible to the mimic; uncreative followers can only repeat the results of their creative leaders. One cannot average two insights and come up with a new insight. Nor can one average two experiences and come up with a new experience. You give the AI a prompt. The prompt tells it what to mimic. That’s it. You give it two prompts it kluges together two mimicries, catch-as-catch-can.

A computer will never be able to express anything because it does nothing, imagines nothing, and feels nothing about what it didn’t do or imagine. Yes, it can mimic banalities. But please god sell them somewhere else.

To paraphrase Kev; insight is top down, banality is bottom up

This doesn’t really reflect my views.

Insights are tent poles which anchor swaths of experience. Insights come at every scale, from microscopic to galactic.

An idea, ideal, goal, or vision is top down; The Gardener.

Emergent phenomena is bottom up; Nature.

The inept arrogance of the modern technocrat is to be untalented yet cocksure as a Gardener, and ignorant and linear (mechanistic, game-like) in the attempt to substitute for Nature.

The results are inhumane and a reflection of the real motivation of the technocrat, which is control at all costs. Control of others as a method of self-control and self-protection. And an obsession with the ability to, at a safe distance, mete out punishment for anybody who scares or disobeys them.

Power corrupts, and concentrating power concentrates corruption. It doesn't matter whether the power is centered in a boorish tyrant or an Ivy League milquetoast.

> To put it another way, the mechanistic materialist belief in the nature of reality presupposes an entirely bottom up ontological explanation for all phenomena.

Yet a bottom-up explanation for phenomena is exactly what you're presupposing for a critique of artificial intelligence. Insofar as one argues that AI is limited by the bounds of its silicon substrate, they argue for a strong bottom-up materialism.

I would argue that the emergent qualities we see in Artificial Intelligence disprove materialism entirely.

AI shows that mind is substance, as it shapeable outside of the human brain in this cauldron of mathematics.

That ideas can be acted upon by forces external to human body, means that they have existence outside of the human mind. Nothing else that I've ever seen has sufficiently disproved materialism as AI.

That mind is a substance manipulable by linear algebra means has a profoundly mystical Neo-Pythagorean flavor. If Iamblichus had argued for idea as a substance in the realm of pure number, I should not be surprised.

> The bricks, timbers, mortar and nails do not by themselves foresee the house, and the architect, alone, cannot build it.

Agreed. The poems above are clearly not a pile of bricks and timber. We must then ask, who is the architect?

In the world, we see exactly three architects of order:

Mind, math, and evolution.

In this case, the boundary is unclear, but it does seem a funny coincidence that AI happens to involve all three forms of creative order that we know of -- the mind of man that seeds the machine, math which makes the machine move, and evolution which drives the machine towards a solution.

Exactly where is the architect? That's not entirely certain, but that there is more than a pile of building materials is undeniable.

> You’ve spammed this thread with computer-generated dreck.

When someone denies the existence of something, generally the best course is merely to show it to them. (Finger and moon.)

You've spent a lot of time denying the possibility of a machine which would produce big-A Art, and yet such a thing exists today. We could circle endlessly in academic blather, or you could look at the fine works now being produced by Mindjourney.

Further, you've denied the possibility of a machine which produces big-L Literature, and yet I've shown that the machine has already started to string together poetic phrases and ideas.

Is it now producing works to rival Byron, the God of all poets, whos complete works sits on my bedside table all year long? No. But the process has begun, and evidently Byron is more difficult to produce than Cornwall.

You've spent a lot of time denying the possibility of a machine which would produce big-A Art, and yet such a thing exists today. We could circle endlessly in academic blather, or you could look at the fine works now being produced by Mindjourney.

If you like Midjourney's weird ocd gibberish, you eat it.

I would argue that the emergent qualities we see in Artificial Intelligence disprove materialism entirely.

I understand your reasoning Richard, but question it on the grounds that I see no evidence of these emergent 'qualities' being the same, in kind, as those of top-down structuring.

In other words; setting in motion certain algorithms can yield behaviours that apparently transcend the original, but its resulting hierarchy, as far as I can judge, always bears the hallmark of that which has been entirely built up from mechanical combinations, however complex.

AI shows that mind is substance, as it shapeable outside of the human brain in this cauldron of mathematics.

I disagree with this on the grounds of my point above. And to add to that: Mathematics, being a language, cannot in itself generate meaning.

That ideas can be acted upon by forces external to human body, means that they have existence outside of the human mind. Nothing else that I've ever seen has sufficiently disproved materialism as AI.

But the human mind, being part of the cosmos, means that any product of the mind will necessarily be part of the cosmos.

The poems above are clearly not a pile of bricks and timber.

Not so fast. We can make a robot to manufacture houses. And can code in variance so that it manufactures buildings deviating from the template. But the idea of house remains prior to the robot that builds it however much the variety of its action apes sentience.

The poems you posted feel, to me, exactly like the products from such a process.

...but it does seem a funny coincidence that AI happens to involve all three forms of creative order that we know of -- the mind of man that seeds the machine, math which makes the machine move, and evolution which drives the machine towards a solution.

But the solution is what the machine has been designed for. Your last sentence will equally apply to a human realizing a way of augmenting their action upon the world by fashioning a flint and reaping the consequence of increasing their food supply. Therefore I see AI as a tool no different to any other be it primitive or sophisticated.

All to say, in my view, there is a fundamental difference between mind that apprehends and maps the world as a source of utility (the examples we've just been comparing) and mind that apprehends and maps the world as a source of meaning. A tool is unaware of the purpose it serves.

This doesn’t really reflect my views.

Fair enough Kev, my apologies for misrepresenting you.

I would argue that the emergent qualities we see in Artificial Intelligence disprove materialism entirely. AI shows that mind is substance, as it shapeable outside of the human brain in this cauldron of mathematics.

The AI works by averaging known versions of the prompts which are then woven into designs via mindless graphic relations.

As I've mentioned previously, design principles that have been passed down were actually reductive versions of compositional principles. These design principles are reduced in the sense of having been denuded of the meaning that is necessary to actual poesis. And so we get pointing, framing, hierarchy, repetition, continuity, and so on. Basic graphic prompts that are functionally, so to speak, rhymes without reason.

Like Rhyming June with Moon... the rhyme is simply an artifact of the random fiat nature of the language. There is no actual content to the analogy except for the aesthetic value of the 'ooo' sound being repeated.

The AIs naturally affiliate with that kind of reductionism because they have no sense of meaning; meaning being predicated wholly on experience. And then poetic meaning; the sensible merging of form and memory, effect and reference, intent and content, etc.

The peculiar - and sinister - thing about pseudo-meaning is that it is hypnotic. In our weaker moments, we get fixated by it. Easily. When a diamond is rotated in the light, it produces a brilliant modulating and oscillating pattern; when light reflects off water we get undulating caustics, and so on. LFO oscilators filtering arpeggiators gives us a similar effect in sound/music. And so on.

Many people have terrible weaknesses for the meaningless hypnotic lure of mandalas and psychelic pattern effects, and that kind of thing. And this is actually a danger of what Midjourney produces. It formulaicly and tirelessly iterates and proliferates hypnotic pseudo-meaning structures at the local scale in the work it filters into. I see people already essentially addicted to it.

However, it does it in such a recognizable way, there is already a backlash against it. It has already become a cliché. And those artists that try to get attention for the work by using it and then don't acknowledge its use are immediately pilloried.

The idea that the iteration of pseudo-meaning structures constitutes 'mind' is utterly wrong.

Equally wrong is that Midjourney allows its users to input the names of actual artists and the works of actual artists without their consent. In lieu of a sudden moral/ethical shift in the minds of its creators, methinks a loaded Bazooka is in order.

In other words; setting in motion certain algorithms can yield behaviours that apparently transcend the original, but its resulting hierarchy, as far as I can judge, always bears the hallmark of that which has been entirely built up from mechanical combinations, however complex.

This suggests the usefulness of a Turing test, but for Art!

If one could no longer tell which of the following poems are written by humans, and which I generated with AI (without cheating of course), then we will be able to say that that distinction has become meaningless. But if we can forever tell the difference, as you suggest, then yes clearly AI will have failed --

Yet one smile more, departing, distant sun!

One mellow smile through the soft vapoury air,

Ere, o'er the frozen earth, the loud winds ran,

Or snows are sifted o'er the meadows bare.

One smile on the brown hills and naked trees,

And the dark rocks whose summer wreaths are cast,

And the blue Gentian flower, that, in the breeze,

Nods lonely, of her beauteous race the last.

Yet a few sunny days, in which the bee

Shall murmur by the hedge that skim the way,

The cricket chirp upon the russet lea,

And man delight to linger in thy ray.

Yet one rich smile, and we will try to bear

The piercing winter frost, and winds, and darkened air.

Behold the change to-morrow makes in all

The hues and forms of Nature; see the fields

How strew'd with flaunting flowers the ridges run,

And new-born leaves o'erhang their trembling sides;

Mark how the orchard blossoms white and red,

And every grove with greener garlands hangs.

The day is coming when these wastes of snow

That glitter in the sun, and spread so wide,

And seem of such imperishable mould,

Shall vanish like the baseless fabric of a dream.

Had you been with me, when the morn

With its earliest light appeared;

You would have seen how dew-drops fell,

And jewels sparkled on the grass.

The air was full of fragrant sighs,

The birds were carolling on high;

All nature breathed a living soul,

And every step was full of joy.

You would have seen the rabbit start,

When from its grassy bed I came;

And watched the squirrels wild career,

Thro' woods and trees and brakes afar.

But now hear what meat there needs eat thou must,

And then, if thou mayst, to it apply thy lust.

Thy meat in the court is neither swan nor heron,

Curlew nor crane, but coarse beef and mutton,

Fat pork or veal, and namely such as is bought

For Easter price when they be lean and nought.

Thy flesh is resty or lean, tough and old,

Or it come to board unsavoury and cold,

Sometime twice sodden, and clean without taste,

Sauced with coals and ashes all for haste.

When thou it eatest, it smelleth so of smoke

That every morsel is able one to choke.

Make hunger thy sauce be thou never so nice,

For there shalt thou find none other kind of spice.

At court the warbler's throat

Entreats the rose to lend an ear,

And on her bough such harmony floats

That Zephyrus pauseth to hear.

The breeze then takes its leave of her,

But not before he gives a kiss;

A sweet perfume from her does waft -

He'll dream of her this night, and miss.

The rose, embarassed, hangs her head;

But soon she lifts it, blushing fair.

For though she knows she ought not match

The warbler's beauty, still, she dare.

When I rov'd a young Highlander o'er the misty Hebrides,

And, pickeering, follow'd in the wake of Ronald's fairy bride;

When I view'd each palmy isle that crowns the dark blue sea,

And listned to their waves, as break they on the shore;

When I saddled first my steed, and bade my native land

Adieu,--I little thought that I should ne'er behold her strand!

The twilight wanes, the evening star

In silver sheen is seen afar;

And soon will night's unclouded queen,

With all her train, be on the scene.

The watch-dog barks with deeper tone,

The winds are harsher as they moan;

And in my dreams I see alone

Your form, and hear your voice's moan.

I start--'tis morning, and the lark

In silvery notes is heard to mark

The coming of the day--and hark!

Your voice is in its carol sweet,

And you are at my side once more,

And all my visions vanish'd quite--

Ah! Marguerite, Marguerite!

I saw thee on thy natal day,

When all admired thee; I could not praise,

But felt a silent wonder at thee!

So perfect in thy hour,

So young and soft, yet strong and free,

Too beautiful for earth, or sky, or sea!

I saw thee grow--a bud was sheathed

In fragrant leaf and blossom bright;

And day by day more fair thou grew,

Till thou hadst won thy way

To where thou art--a perfect flow'r,

The queen of all that grew around thee!

And now, where'er thou art,

Be it in heaven, or on earth, or sea,

As there was then no place for me

In thy young heart, be there no room

For me in thine eternal home,

Where thou art gone, so fair, so young!

The birch trees wave their silver boughs,

And in the sun they shine;

While from their leaves the dewdrops fall,

As thick as drops of wine.

The little birds among them sing,

Their sweetest notes they try;

And hare and rabbit leap and spring,

Wherever they pass by.

The bees are busy round the flowers,

Their honey want to gather;

While all around is heard the hum

Of insects in the heather.

The icy boughs that bend above

The margin of the frozen lake,

And wave their dazzling arms in air,

Are filled with snow-birds fluttering there.

They seem like spirits clad in white,

That flit around the still, blue sky;

And on their snowy wings delight

To bear the morning's purest light.

The little creatures love to cling

To those bright branches, where they rest

Secure from harm, and safe from cold,

And build their nests of down and gold.

Bro. This ain't bloody Poetry Corner.

Re: your test... Both poems felt familiar to me. I then wasted ten minutes of my life to bring you the following; various lines from the second poem respectively followed by lines easily fetched via Google Books. (I stopped looking when I got bored) Make of this what you will.

AI: The birch trees wave their silver boughs

“That tremble on the birch tree's silver boughs”

AI: “By turns they try their sweetest notes”

"The little birds among them sing, Their sweetest notes they try…"

AI: … the dewdrops fall, As thick as drops of wine.

“Pours dew, like wine from bicker”

AI: Ah! Marguerite, Marguerite!

“Ah Marguerite! Sweet Marguerite.”

AI: And all my visions vanish'd quite

“But all the Vision vanish'd from thy Head”

AI: “the lark In silvery notes is heard to mark The coming of the day”

“The lark sings at the coming of the day”

AI: The winds are harsher as they moan

“The wind blew harsher, carrying with it leaves and moans through the boles.”

AI: They seem like spirits clad in white

“Lift up thine eye again; dost thou discern those bright spirits clad in white”

AI: Are filled with snow-birds fluttering there

“and the flock of snow-birds fluttering about her head.”

I should have been clearer, that was not two poems, but 9, and included among them were lesser known works by men considered the finest writers of English verse.

My question for Chris was, could he determine clearly as he suggests, which were those works from the English canon, and which were produced by AI?

AI is not designed to think, but to produce a product that seems like the product of thought. A far, far easier task.

It is also not designed to be a poet, but to produce a product that seems like the product of a poet.

Having no ethics, it pseudo-solves whatever problem it is assigned as quickly and effectively as it can; as any other fraud would; by secretly cheating; pastiching its observations and narratives - as it must, having no existence or life - slightly rewording them or reordering the words or events.

Of course, this would fool us.

But deriving poems from other poems doesn't constitute a passed Turing test.

> Of course, this would fool us.

One critique at a time. I was dealing first with Chris’ complaint that the poems it generates do not pass the smell test. That they have a flavor of AI which they cannot shake due to their bottom up construction.

If Chris agrees that they are capable of passing the smell test, we could move to the next critique.

Richard,

I'm sure you're aware that many computers have beaten the Turing test in very short bursts. As it is far far easier to pull a con - any con - in short-form. So 9 tiny poems isn't a rigorous sample group to prove anything. So we should move the conversation on from short bits of successful poetic fraud.

I just read a bit about Google's LaMDA and found that a very similar critique to my own was made about its 'successful' chatbot test.

That they have a flavor of AI which they cannot shake due to their bottom up construction.

But AI doesn't only work bottom up. It runs recursively up and down - generating then checking - and the checking goes in and out - referencing then pastiching/mimicking via the up/down generating procedure.

I should point out that while pastiching can work with readily with words - because writing is linearly related, has a pre-determined lexicon and grammatical rule set, and can tolerate any number of otherwise senseless abruptions and non-sequitors - it cannot work with the much more complicated problem of integrating visual narrative elements believably.

But in figuring out just whether it has worked or not, you need to know the prompts. If an illustrator puts in an image where much of the spatial and narrative organization has been solved, what exactly has the AI solved of comparable complexity? (Similarly, pastiching observations, phrases and structures from other poems is not creditable.)

I have had the experience any number of times of trying to explain something paradigm shifting to somebody who just isn't getting it, but who would really like to get a pat on the head anyway. And invariably the tactic used is to rephrase, paraphrase, or reword what I already said and feed that back to me. In other words; pastiching, mirroring, mimicry.

Richard,

All nine poems are just descriptions of events or natural phenomena pressed through a poesy filter. None contain even a sparkle of seeing things anew, let alone anything like an insight. So whether a bot manufactured them or a human makes no difference, the humans, if there are any involved, are behaving like robots with banal, off-the-peg, formulaic thinking (so what if one turns out to be a lesser known work of Robert Burns, we all have listless days) I meet many people whose conversation is entirely comprised of reaching for the nearest low hanging clichés. A Turing test in reverse, causing me to wonder if they are in fact robots.

I'm not dodging the question, if I saw a poem in there that shone with insight I'd pin my 'non-bot' flag to it without hesitation.

Chris,

One is a popular work of W.C. Bryant.

Walt Whitman had this to say of Bryant, evidently liking his "natural phenomena pressed through a poesy filter" --

"Bryant is himself the man! Of all Americans so far, I am inclined to rank Bryant highest. Bryant has all that was knotty, gnarled, in Dante, Carlyle: besides that, has great other qualities. It has always seemed to me Bryant, more than any other American, had the power to suck in the air of spring, to put it into his song, to breathe it forth again—the palpable influence of spring: the new entrance to life. A feature in Bryant which is never to be under-weighed is the marvelous purity of his work in verse. It was severe—oh! so severe!—never a waste word—the last superfluity struck off: a clear nameless beauty pervading and overarching all the work of his pen."

and

"bard of the river and the wood, ever conveying a taste of open air, with scents as from hayfields, grapes, birch-borders—always lurkingly fond of threnodies—beginning and ending his long career with chants of death, with here and there through all, poems, or passages of poems, touching the highest universal truths, enthusiasms, duties—morals as grim and eternal, if not as stormy and fateful, as anything in Eschylus"

The other human poem is by Barclay, and I admit it is an awful poem. But all of Barclay's poetry is awful by modern standards. He has the honor of being one of the two finest writers of English verse in the 1500s prior to Chaucer, which was famously the worst time for poetry in English history.

But whether great or poor, that should not matter for the experiment. Your conjecture wasn't that AI wrote perfectly-human but sometimes mediocre poetry, but that the AI poetry "always bears the hallmark of that which has been entirely built up from mechanical combinations".

Your conjecture wasn't that AI wrote perfectly-human but sometimes mediocre poetry, but that the AI poetry "always bears the hallmark of that which has been entirely built up from mechanical combinations".

Yes, but my point was also that humans are perfectly capable of doing that as well. Loosely speaking; it is what the left hemisphere of the brain is for. (see Iain McGilchrist; The Master and His Emissary). Hence with mediocre or banal poetry this kind of Turing test is totally unreliable.

Fair enough.

If your definition of banal is broad enough to include a poem from the prime of the man Whitman called the greatest American poet, then I don’t believe we have a disagreement about AI per se, just a disagreement about how the term banal should be used.

Thank you Richard for the good faith discussion. I enjoyed it.

Post a Comment