I always wondered if his painting meant that Schwartz felt trapped in his career as a commercial artist.

Friday, October 28, 2022

DANIEL SCHWARTZ EXHIBITION

Sunday, October 23, 2022

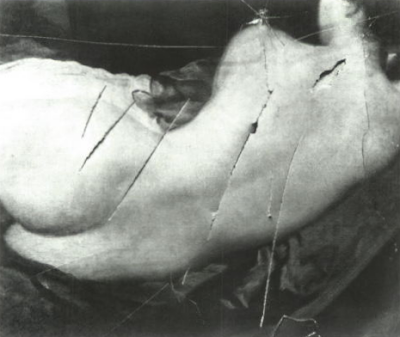

CRIMES AGAINST ART, part 2: MARY RICHARDSON

I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history.... If there is an outcry against my deed, let everyone remember that such an outcry is an hypocrisy so long as they allow the destruction of Mrs Pankhurst and other beautiful living women, and that until the public cease to countenance human destruction the stones cast against me for the destruction of this picture are each an evidence against them of artistic as well as moral and political humbug and hypocrisy."

Richardson was imprisoned for six months, which was the maximum penalty under British law for destruction of an artwork.

As we've previously discussed on this blog, the ability to create great art is very rare, yet any moron has the ability to destroy it. Perhaps that's why accountants never make good artists: art's odds are so terrible, a career in art would make no sense to anyone who understands math.

Tuesday, October 11, 2022

CRIMES AGAINST ART, part 1: SCRANTON, PENNSYLVANIA

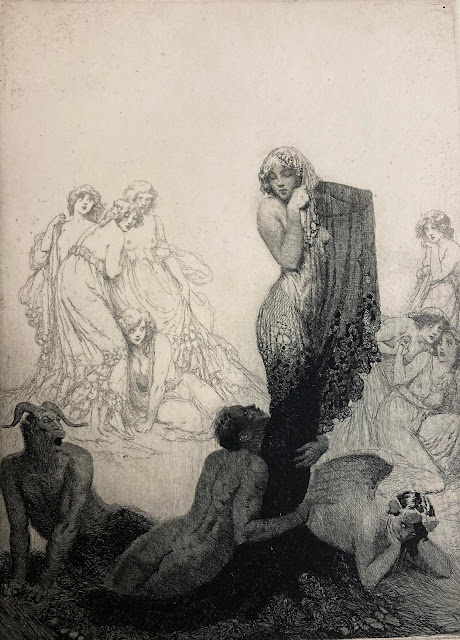

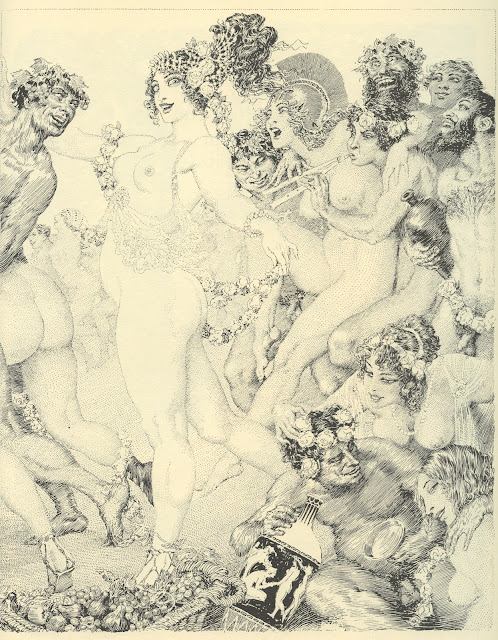

The Australian artist Norman Lindsay may have been the most randy illustrator of the 20th century.

|

| Norman and Rose Lindsay |

Fearful that they would never return to Australia, Rose brought all of her prized possessions with her, including 20 years worth of Norman's best work. Her daughter Jane recalled, "Large crates were specially made and into them she packed everything which she cherished as beautiful and valuable-- hundreds of exquisite watercolours, pen drawings, etchings...."

The couple docked in California and made their way across the country by train. The crates with art were loaded onto a wooden freight car immediately behind the engine. When the train reached Pennsylvania the freight car caught fire. The train pulled off into the small town of Scranton where the good citizens helped put out the fire and saved as much of the art as they could on the train platform.

However, when they saw the scandalous pictures they had saved, the citizens became so upset that they piled up the artwork and and set it back on fire again "before corruption could set."

Lindsay's artwork survived a world war and a fire, but it couldn't survive the morality of the citizens of Scranton.

Friday, October 07, 2022

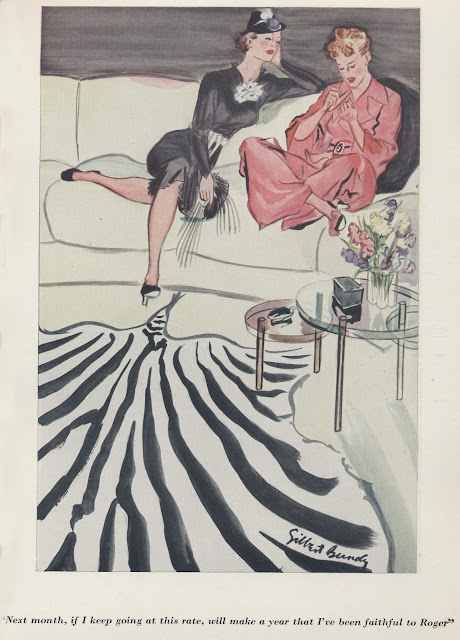

ANOTHER CHANCE AT PICTURE MAKING

|

| Bundy sketching his daughter at home, circa 1947 |

|

| The dog in front of the mural was named Emmett Kelly. |

... but it eluded his grasp. Bundy began drinking heavily. His daughter recalled hearing him weeping behind closed doors and threatening to commit suicide. One day he held her close and said, "War is never worth it." His marriage fell apart. He moved out and his wife painted over his mural, sealing that chapter forever.

,_1647-51,_01.jpeg)

.jpeg)