"To live is to war with trolls." -- Henrik Ibsen

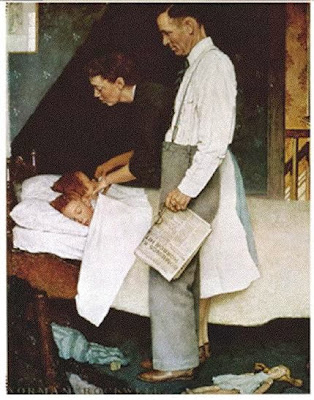

One of the most interesting stories from Deborah Solomon's new biography of Norman Rockwell involves his famous series of paintings, the Four Freedoms. During World War II, Rockwell wanted to aid the war effort but was too old to enlist and not physically suited to be a fighter. He set out instead to illustrate Franklin Roosevelt's "Four Freedoms" in a way that would inspire patriotism and encourage the purchase of war bonds.

After sketching his four paintings, Rockwell went to Washington to donate his art to the government but the government wasn't interested. Rockwell showed his drafts to the Office of War Information but the official in charge responded:

The last war, you illustrators did the posters. This war we're going to use fine arts men, real artists. If you want to make a contribution to the war effort you can do some of these pen and ink drawings for the Marine Corps calisthenics manual.

Solomon deduces that the official who rejected Rockwell's art was the "pompous" Archibald MacLeish, poet and Pulitzer prize winning playwright. MacLeish was the Assistant Director of the agency. He said he preferred to inspire the country with pictures from "real" artists such as Marc Chagall, Salvador Dali and Japanese artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi (6 months after Pearl Harbor!)

Rarely has a misguided act of cultural arrogance been so promptly, thoroughly and satisfyingly refuted.

Stung, Rockwell took the rejected paintings to the Saturday Evening Post which used them as internal illustrations. Editor Ben Hibbs later wrote:

The results astonished us all....Requests to reprint flooded in from other publications. Various government agencies and private organizations made millions of reprints and distributed them not only in this country but all over the world. Those four pictures quickly became the best known and most appreciated paintings of that era. They appeared right at a time when when the war was going against us on the battle fronts, and the American people needed the inspirational message which they conveyed so forcefully and so beautifully.The Post received 60,000 letters about the paintings:

Subsequently the Treasury Department took the original paintings on a tour of the nation as the centerpiece of a Post art show to sell war bonds. They were viewed by 1,222,000 people in 16 leading cities and were instrumental in selling $132,992,539 worth of bonds.

In the meantime, the imperious Archibald MacLeish lasted a mere eight months in his job at the Office of War Information. After he left, the OWI sent a film crew to Rockwell's studio and filmed a five minute newsreel about his Four Freedoms. The government's newsreel played in movie theaters around the country.

MacLeish was a brilliant intellectual but he let his reflexive cultural arrogance substitute for thinking about what type of art would be effective. In doing so, he became just one more of those obstructive trolls described by Ibsen.