The possessions would have to be auctioned off to pay Rembrandt's debts. Moving from room to room, it didn't take long to figure out why Rembrandt had gone bankrupt. As Anthony Bailey wrote in his book, Rembrandt's House:

The house was crammed with pictures, stacked against and hanging from the walls.... [T]he collecting trait appears to have become an ungovernable compulsion.Bailey reports that these pictures included "bits and pieces," scraps and sketches that Rembrandt fancied by his contemporaries, drawings from Italy, paintings from different periods in a variety of styles.

In part he collected... pieces that he could use in his works, not just for themselves but as pointers and touchstones. [B]ut his collection of pictures was huge and diverse. Rembrandt's collection was almost a museum.I thought about poor bankrupt Rembrandt recently when I viewed the current exhibition at the Society of Illustrators of the art collection of the illustrator Peter de Sève. The exhibition includes work from greats such as Rackham, Searle, Kley, Frazetta, Frost, Sullivant, Disney artists, Winsor McCay and many others.

Unlike a typical museum exhibition organized by a curator or art historian, de Sève has assembled work that appeals to his artist's eye.

He includes working drawings that reveal the thought processes of the artist:

|

| Jules Feiffer |

Preliminary sketches that reveal the original spark of inspiration before the concept has been refined and diminished.

|

| Frazetta |

|

| Frazetta |

|

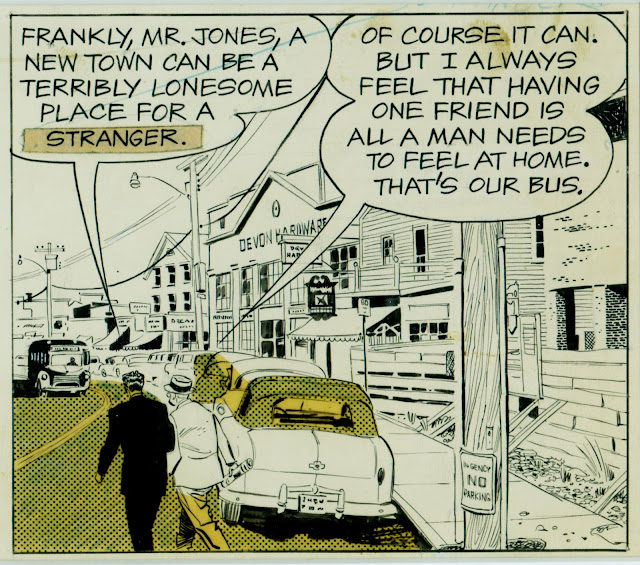

| A dog racing down the road... |

|

| ...leaves disaster in its wake. |

and moving on to Winsor McCay's Gertie the Dinosaur at the dawn of animation...

...before turning to great Disney art such as Preston Blair's famous hippopotamus ballerina from Fantasia and art from Lilo and Stitch.

There's strong pen and ink work by artists such as Heinrich Kley:

... and work by Arthur Rackham that reveals the artist's underlying sensitive pencil lines:

|

The exhibition also contains final work with interesting solutions by fellow illustrators:

|

| As fearless with watercolor as he is with ink. |

|

| Valentine from de Sève's daughter Paulina when she was five years old. |

Paulina's picture exemplifies what makes an artist's exhibition so interesting. De Sève isn't misled by the pretensions and superficial considerations that preoccupy so many curators and art historians. Instead, he hones right in on the nutritional content; all marks on paper are judged on a level playing field.

At the entrance to the exhibit, De Sève writes: "The artist I've become is a result of the things I've learned, and continued to learn, from others."

When the Amsterdam Insolvency Office finally shows up at de Sève's door, you'll want to be there for the auction.