Another bright, shiny apple in the cornucopia of the 1960s comic page was Apartment 3-G (1961-2015).

|

| Kotzky and his son, Brian, who would eventually take over the strip |

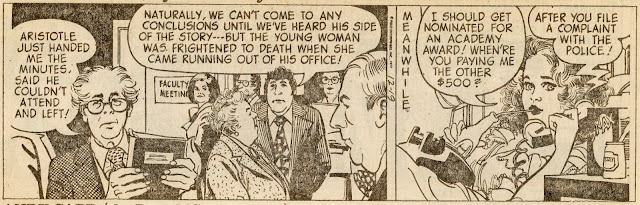

Kotzky spent years illustrating comic books, advertisements for the renowned ad agency Johnstone and Cushing before serving as a ghost artist on strips as varied as Steve Canyon and Juliet Jones, he finally landed his own syndicated strip, Apartment 3-G, and from that moment on he worked like a dog for the privilege.

The best history of Apartment 3-G and the other photorealistic strips of the era was Prof Mendez's beautifully written The Look of Love: The Rise and Fall of the Photo-Realistic Newspaper Strip, 1946-1970. In it, Mendez describes Kotzky's exhausting work process:

Kotzky would rough out the week from the script given to him by Dallis then would go off to find "the right reference files," four layers in all. The first layer was the use of celebrity photographs--celebrities because of the ample supply available--for faces. Whenever a new guest star was introduced, Kotzky would spend considerable time finding the right actor to cast then developing how his version of the character would appear in his strip, his vibrant line masking the identity of the real person used. The second layer was instant photographs for body positions, the animation of the gesture into story, drafting family and friends for posing duty. Brian noted his father didn't deviate from using the camera until the very end of the strip. The third layer, mostly for women, was the transposition of the latest fashions from glossy magazines, necessary because the girls always had to look stylish and up to date. The fourth and final layer was the use of photo scrap for concrete details-- telephones, lamps, desks, purses and briefcases, stairways and mailboxes.

It's no wonder that Kotzky's son recalled, "As far back as I can remember, Dad did nothing but work. No vacations, no hobbies, no sitting around reading the Sunday paper--it was a life spent at the drawing board." Kotzky died with an uncompleted Sunday page still on his drawing board.

Like every other illustrator who worked in the 1950s, Kotzky seems to have studied the great Al Parker's treatment of women:

Apartment 3G was never quite in the same league with the very top strips, such as Alex Raymond's Rip Kirby or Leonard Starr's On Stage, but that's not my point. It was a smartly drawn, tasteful strip which year after year, demonstrated skill and craftsmanship. There is no strip that comes close to it on the newspaper comic pages today.

Comics pages in the 1960s were overflowing with fine drawings. A young boy who couldn't afford 12 cents for a comic book could still receive a fresh gallery of free drawings every day. He could observe and learn from their use of line, their compositions, their solutions to problems, their anatomy lessons. He might even cut out the strips he liked and carefully preserve them in a special shoebox. Then one day in 2022 he might take them out again and fondle them, a little surprised by how they (and he) have turned brittle with age.

Sadly, this is what Apartment 3-G looked like when it finally crawled across the finish line in 2015:

As Shakespeare said, “sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

Young children who love pictures have to turn elsewhere for inspiration and guidance these days. This school is closed.