Andrew Wyeth painted this picture shortly after the muscles in his shoulder had been severed. He couldn't even hold a brush without supporting his hand using a sling suspended from the ceiling.

Wyeth suffered from bronchiectasis, a frequently fatal disease, and had most of a lung removed in a major operation in which he nearly died. During the operation, doctors severed his shoulder muscles and it was questionable whether he would ever paint again. While recuperating from his operation, Wyeth struggled to paint this picture. Every blade of grass must have been painted in pain.

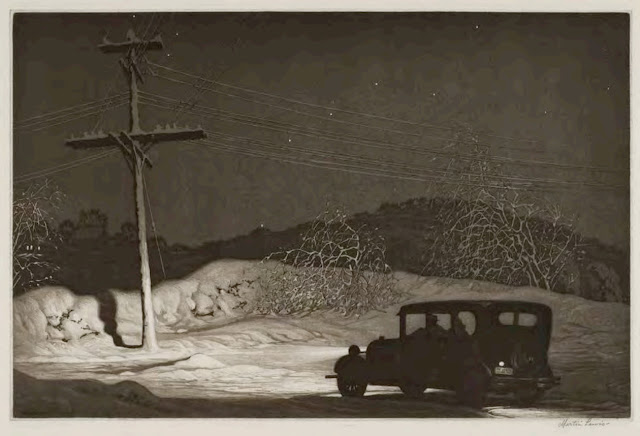

Bernie Fuchs painted this next picture seven years after three of his fingers had been sliced from his drawing hand in an industrial accident.

When he got out of the hospital, he couldn't even figure out how to hold a piece of charcoal with his remaining fingers. No one believed a career as an artist was remotely feasible.

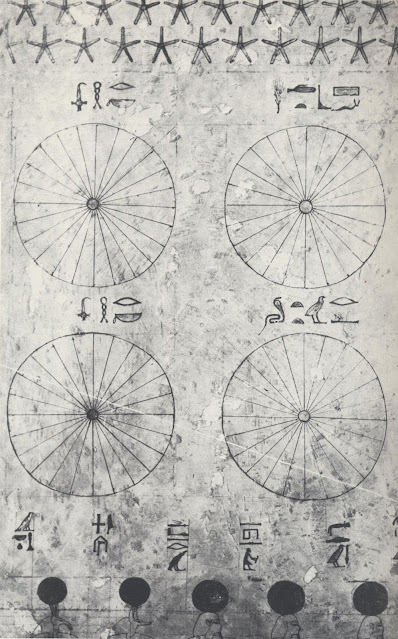

Degas suffered from poor vision his entire adult life, and by his forties was virtually blind in his right eye. By the time he turned 60, he frequently wore spectacles that were completely blacked out except for a small slit in the left lens. It was under these conditions that he painted several of his masterpieces, including this picture:

It's amazing how many great artists started out with bad breaks and terrible odds.

The fabulously successful Al Dorne was born in the slums of New York and grew up fatherless in abject poverty. As a child suffering from tuberculosis, malnutrition and heart disease, it appears that he only survived because a social worker ordered him removed to a charity hospital. Dorne quit school after 7th grade to support his mother, two sisters and younger brother by selling newspapers on a street corner. He taught himself to draw by looking at the pictures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Even the aristocracy of illustration such as Norman Rockwell or Mead Schaeffer or Henry Raleigh scratched and clawed to overcome the odds as starting illustrators after their peers had become daunted and gave up. Rockwell spied on his idol J.C. Leyendecker to learn his techniques. He lied to the art director of Collier's, claiming to be from San Francisco because he heard the art director favored artists from San Francisco. Mead Schaeffer snooped on an art director's desk and intercepted an assignment intended for another artist.

Perhaps because they grew up in a dog-eat-dog world with no illusions about what it took to survive, these great artists also tended to seek out the toughest most demanding teachers they could find, teachers who'd regularly beat the stuffing out of them.

Robert Fawcett went on a pilgrimage to London to study for two years at the Slade School, which was in those days a grueling, medieval type institution famous for teaching students to draw through old fashioned traditional methods which Fawcett described as "torture." Norman Rockwell took lessons from the demanding George Bridgman who scolded his students that they'd end up shoveling coal for a living. Rockwell also valued the critiques from Leyendecker who taught by "tearing my pictures to pieces." Rockwell said, "You never ask [Leyendecker]... what he thought of your painting unless you wanted a real critique; he thought nothing of [saying]...You'd best scrap it and start over." Mead Schaeffer walked away from a scholarship at Pratt to learn by cleaning Dean Cornwell's brushes for free because he valued Cornwell’s blunt criticism: “[Cornwell] didn’t pull any punches. I learned so fast that I did three years in one. It was a great stroke of luck.... Dean Cornwell was the single most important contributor to my development.”

Andrew Wyeth said that he submitted himself to not one but two harsh masters: "Jesus, I had a severe training with my father, but I had a more severe training with Betsy [his wife]."

Perhaps these artists had heard the call from Walt Whitman:

Have you learned the lessons only of those who admired you, and were tender with you, and stood aside for you? Have you not learned great lessons from those who braced themselves against you, and disputed passage with you?

I've thought about this in recent years as I've read about disputes at some of today's prominent art schools for illustrators. I've read complaints on social media from students who say that their instructors don't make them feel "validated" and aren't sufficiently "encouraging." I've read web platforms that have been set aside as "safe spaces" where art students can complain about their schools or instructors without the school or instructor being permitted to respond or dispute the story. I've read complaints that instructors have given poor grades without due consideration to how students have felt traumatized by the recent political environment.

As a general matter, I think everyone should treat everyone else with sensitivity and fairness. I also think the priorities now being expressed are likely to increase the number of art students who feel validated. However, looking back at the types of artists who not only survived but thrived in changing markets, these recent exchanges don't seem destined to foster resilient, successful illustrators.

Perhaps an art history class on basic survival skills should be added to the modern curriculum.