But this Frazetta drawing...

...was taken directly from a Life Magazine article on a day at the beach:

The great illustrator Robert Fawcett warned his fellow artists against becoming dependent on photography: "photography has been abused, to the point where many illustrators are afraid to put pencil to paper without first photographing their subject exhaustively." Yet when he needed to draw a south sea island native...

...he relied on this photo from Life Magazine:

Norman Rockwell was one of the most successful illustrators in America when he secretly began using photographs. When his peers asked if he used photographs, he lied:

At a dinner at the Society of Illustrators, William Oberhardt, a fellow illustrator, grabbed my arm and said bitterly, "I hear you've gone over to the enemy." "Hunh?" I said, faking ignorance because I realized right way what he was referring to and was ashamed of it. "You're using photographs," he said accusingly. "Oh...well... you know...not actually," I mumbled. "You are ," he said. "Yes" I admitted, feeling trapped, "I am." "Judas!" he said, "Damned photographer!" and he walked awayI am interested in why some of the most confident, successful illustrators felt ashamed to use photos. And why, despite their shame, they thought the benefits were worth it.

Since those early days, attitudes about using photos have changed but the role of photos has changed even faster.

What started as using photos for reference evolved into projecting photos directly on the page, which then developed into light boxing, which changed to scanning photos, later altered with increasingly subtle filters that transform scanned images into a pastel drawing or a watercolor painting or a mezzotint. To make a caricature today, we have only to apply the Photoshop "liquefy" tool to a photo of a face. To improve a composition, we have only to employ the "divine proportion" tool. Technology has played an increasingly vital role in picture making, encroaching more and more on what was once the human core. It remains to be seen whether artists are following in the footsteps of John Henry.

Far from being resolved, the question "how much dependence on a machine is acceptable?" becomes a new question with each passing decade.

In this context, I think it becomes incumbent on each of us to make our own peace with the point along the spectrum where the role of the machine becomes too great.

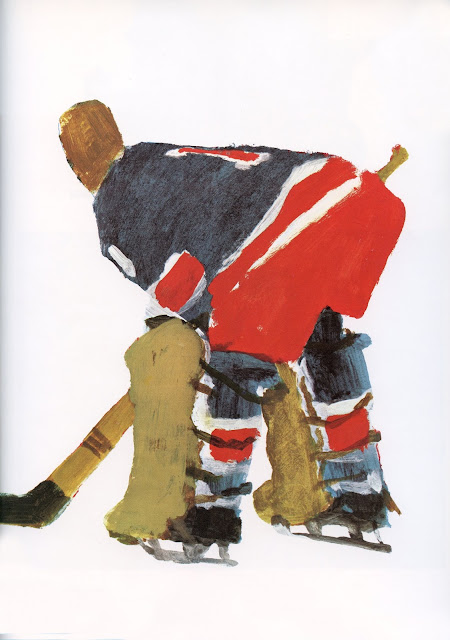

I think the talented Matt Mahurin is a prime example of an artist working interchangeably in traditional media, photography, and film:

I find his work, which blurs the line between photos and hand crafted images, imaginative, powerful and personal. Mahurin writes:

When a client decides to call me, it's not because they are in love with my color palette or feel they can't live without my sense of composition. I am hired for the way I think-- my ability to express clear thoughts and powerful emotions visually. Often the technique or style I use to complete an image is merely an afterthought, no more important than the physical act of typing up what already flourishes in the writer's heart and mind.But perhaps the real challenge to the boundary between art and machine-created images is posed by photographs that today seem to inspire more reverence and awe than more traditional hand made arts do.

|

| NASA's "pillars of creation" |

Pictures adorning Renaissance altars and palace ceilings were valued as high art in part because they elevated viewers by giving them a sense for the sublime. It has been a long time since traditional, hand made arts have aspired to that role.