" I don't know whether this is the best of times or the worst of times, but I assure you it's the only time you've got."

-- Art Buchwald

I recently attended a talk at the Society of Illustrators where the speaker declared that the 1960s were "the golden age of illustration."

But in the 1960s, illustrators believed the golden age was already over. The Society's Annual asked, "Is illustration over the hill?... I don't think illustration will ever regain the popularity it once had." Illustration historian Walt Reed explained why the 60s were actually wretched for illustration: "Television had stolen the fiction magazines audience and illustration's former position as a pace setter for popular culture was usurped....Illustration's role became more incidental and decorative."

It seems that every generation of illustrators is convinced they missed out on the good times.

Back in 1927 a prominent art critic insisted that the golden age of illustration occurred in the late 19th century, and that the field went downhill at the start of the 20th century. In his essay on the decline of illustration, he asserted:

[Illustration] soon departed from the decent standards of the old school, and so debased drawing into the cheapest form of mechanical ingenuity —slippery, sentimental stuff.... As connecting links between the old and the new orders, I may mention Charles Dana Gibson and Howard Pyle.

Gibson, he complained, "was limited and mediocre, and despite the most valiant efforts was unable to learn the first principles of draftsmanship." Pyle, he claimed, was a "prolific hack." He mourned that by 1915 the field of illustration was disintegrating because "the leading American magazines have discarded illustration."

In the following generation, another great historian-- Henry Pitz-- had a different view of the golden age. He claimed that the era of Gibson and Pyle had been the true golden age. He insisted that it was the next generation of illustrators in the 30s and 40s who had gone astray; they became obsessed with mere design. For these callow youngsters, "momentary impact was to be of more importance than leisurely scrutiny of content. Character delineation slips away from us-- no one over 21 has much right to appear on a double spread."

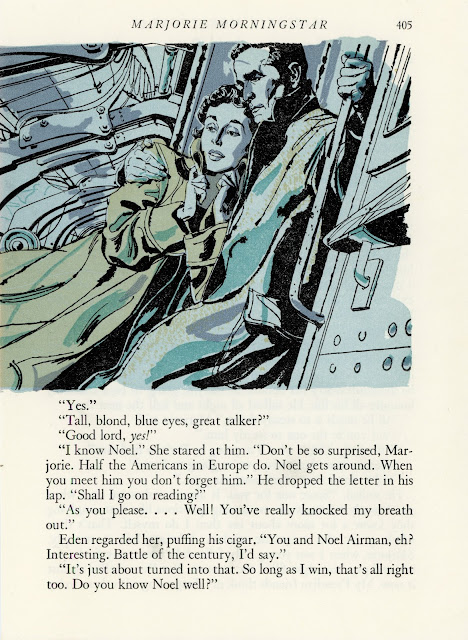

Yet, later generations would look back on the 30s and 40s as "the glamour years." By the 1950s, according to the Society of Illustrators Annual, "the glamour years of illustration had passed. The reading public was diminishing....The role of the illustrator as a means of enticing readership was dwindling." Gone were the big budgets and generous deadlines for illustrations painted in oil on big canvases. Gone were the deluxe illustrated books and the magazines filled with costumed adventure stories. Illustrators were painting in smaller scale on illustration board using fast drying paints.

Later generations saw things differently. They would look back jealously on the bountiful 1950s, the era of The Famous Artists School, with talented artists such as Rockwell, Briggs, Dorne, Fawcett, Ludekens, Parker, von Schmidt, Helck, Gannam, Sickles and others. Al Dorne drove a custom Mercedes with a burled walnut dashboard and a pull-out bar. His steering wheel had Dorne's initials engraved on a silver plate below a star sapphire. That sounded pretty good to later generations.

And so it went, on and on. The good years were always yesterday. The current market had always become terrible.

Scholar Walt Reed described the dire condition of illustration in the 1990s:

Recycling already-published images inexpensively through huge image banks is changing the financial foundation of the field.... [Illustrators] are increasingly replaced by a novice with Photoshop....the bread-and-butter work is vanishing.

Artists tried to keep up with the changing times. Pioneers of technology thought the future belonged to "internet art" but artists have already been warned that post-Internet art is the "new aesthetic era."

So what lies ahead? This cycle of destruction and renewal over the past 125 years of illustration should make us cautious about predicting the end of illustration. But can this history teach us anything about survival as illustration enters the brave new world of generative Artificial Intelligence?

|

| John Cuneo |

In the next few days I'd like to offer you some examples and pose some questions regarding whether this is really the end of the road for illustration as we know it. But even before we start, the one thing we can be certain of is that Art Buchwald was right:

"I assure you it's the only time you've got."