In 1952, Norman Rockwell did the exact same thing with his cover painting for the Saturday Evening Post, "A Day In The Life Of A Girl."

A less observant artist might use the same skin tones and hair color throughout the painting, if only for continuity in a complex composition. Not Rockwell. His power of observation was exceeded only by his work ethic.

The only way to appreciate Rockwell's accomplishment is to view the original painting at the Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass. Unfortunately, I have only a scan of a dull print to reproduce here. Perhaps it will give you enough of a taste so that you will find it worth your while to check out the original. If you like Monet, it will be well worth your time.

The opening vignette is gilded with a brilliant yellow white color (that unfortunately does not show up well on the printed cover).

Next he shows the children illuminated by the light of the silver screen:

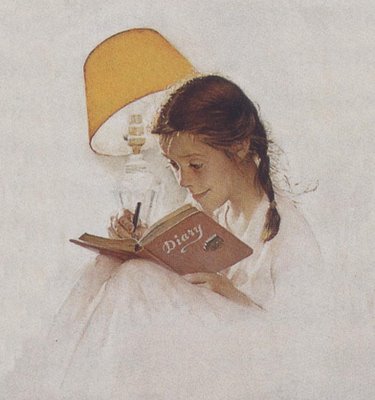

Contrast the cool light of the moon above with the warm glow of the bedside lamp as the girl fills out her diary:

Comparing Rockwell and Monet solely for their studies of light (without all the distracting smoke and mirrors from overfed publicity agents and Manhattan auction houses) I think Rockwell's painting accomplishes more than Monet's. Rockwell portrays more variations in natural and artificial light, working in a smaller, humbler space, with more sensitivity and technical skill than Monet. Rockwell's handicap was of course the sappy story line, which was designed to please the 1950s readers of the Saturday Evening Post. But if you put aside the content and pay attention to the things that matter to an artist, you will see that Rockwell's artistic challenge was the same as Monet's. The real subject of Rockwell's painting, like Monet's haystacks, is the effect of changing light. If you're looking for a safe commodity to invest in, pick the Monet. If you're ready to learn something about light, pick the Rockwell.

6 comments:

Monet painted his haystacks in the 1890s, and it wasn't about capturing the photorealistic details of the effects of light on skin. It also wasn't simply about demonstrating "how light and atmosphere transform an object." (Other artists, such as J. M. W. Turner, Casper David Friedrich, Caravaggio, the majority of the Romantics, and the Dutch still life painters were doing the same thing, many decades before Monet.)

Rockwell's paintings have nothing to do with the concerns of Monet's paintings, except for the effects of light on a surface (which most artsits, throughout history, have been obsessed with). To compare Monet's haystacks to Rockwell's painting is grossly unfair to Rockwell. Rockwell was going for one day in one life and the color changes that you highlight are subtle and fall within the same muted tones and limited color palette. Monet's haystacks were done at various times of the day and the year, and resulted in vividly colorful paintings, all of which had wildly varied and different palettes.

Monet's paintings were also about painting itself, and represented a severe break from the studio based landscapes that were then in vogue. Not only that, but Monet took up loose brush strokes (which were also out of vogue) and utilized them to create vivid color. Representation, per se, was never an interest of any of the 'impressionists' (which is why the critic Leroy derided it with the term, and which is why it was hated as sloppy work that didn't bother to represent the objects in the painting accurately).

Also, all of the 'impressionists,' Monet included, were greatly interested in the new scientific theories of optics - and not interested in how to represent the effects of light as a photograph could, but how color and gesture were interpreted by the eye, esp. how a painter could place two vivid brushstrokes of different solid colors next to each other, and how our eye would interpret it as a third color.

Reducing Monet and the haystacks to a demonstartion of "how light and atmosphere transform an object" greatly misses the point, and also denies that many artists did the same thing years before Monet, such as J. M. W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich, not to mention the great Dutch still life artists.

thoguh the study of light in the rockwell painting is beautifully done, the faces themselves veer towards caricature, and provide a jarring contrast to the more sensitive qualities of the picture.

i agree with the comments. impressionism is about color, broken color specifically, and not so much about very detailed representation. the subject and and how closely it is represented is second to color...looking at your examples even point to that fact; the monet's are quite vivid and stunning, the rockwell's are more muted and draftsmanship is the star.

one thing that has always bothered me about rockwell is his tendancy to make life 'cute'. there is no doubt that the man was an amazing draftsman. there is no doubt that he painted quite well. for me its the subject matter and how its depicted. he sentimentalizes life. he made a lot of paintings about what we like to think life is like, but it is not, like looking back with rose colored glasses on old times that maybe in reality not so rosey.

anyway, i enjoy the blog, and really enjoy your thoughts. even though i disagree with this particular post, i find it an interesting comparison, and apparently thought provoking one.

keep up the great blog! :)

Julia Lundman Midlock

well maybe Rockwell's "sappy storyline" ultimately undid his play on light, while Monet simply choose to show what he was trying to say.

Rockwell certainly was a skilled painter and draftsman. That said, the message in his work feels false and manipulative. It's what you say with whatever talent you have that matters to me. But hey, there's big money in corny, sappy work... just look at Thomas Kinkade. Kinkade paints light well too, in fact he's the self anointed "painter of light". If I want light, which I do, I'd rather look at a Monet. The mood, message and motive seem genuine and I feel he's seeing somthing that maybe I've overlooked.

Perhaps there is another reason for Rockwell's depictions. I was thinking that if an artist portrays a scene rather than just a portrait, whether a person or a flower or whatever, he is making a statement in a subtler way than a political cartoonist.Possibly he is trying to affect the public's actions or conscience. That kind of artist is after all saying something to the people and perhaps he is trying to exert a positive influence upon the population. Think of all the heroes that have come up through our books and films depicted by authors, film makers and artists. Maybe, just maybe, we again need artists who need to show what life should be like, rather than how bad it really is. If the message seems sappy or corny, maybe that is an effort to be a little less subtle as it seems a greater part of our population seems to prefer to have other people do their thinking for them.

Post a Comment