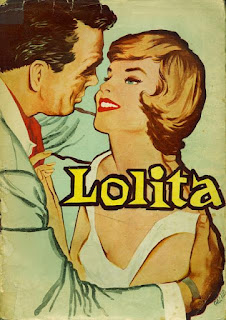

It's hard to think of a more challenging test for realistic illustration than Vladimir Nabokov's book, Lolita. Nabokov emphasized to his publisher that any illustrator who attempted a representational image of the character would be missing the point. He wrote: "There is one subject which I am emphatically opposed to: any kind of representation of a little girl."

The difficulty of illustrating Lolita has been widely recognized. The (excellent) book, Lolita; The Story of a Cover Girl contains essays and dozens of images on "Vladimir Nabokov's novel in art and design." Lit Hub compiled a (useless) survey, The 60 Best and Worst International Covers of Lolita and here are 210 covers over the years. In 2016 The Folio Society produced what they called the First-Ever Illustrated Version of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita."

Many artists and art editors have tried coming up with realistic illustrations for Nabokov's psychologically complex novel but the results have been pretty worthless:

|

Illustration for the recent Folio edition

|

You may not think much of the talents of these particular illustrators, but replace them in your imagination with your favorite representational illustrator. Is there a facial expression or a pose or a color scheme that you think would be more successful?

Now contrast the representational images above with the conceptual illustrations below, often using photography or graphics.

In my view, these conceptual illustrations are far more impressive; they get closer to the meaning of the book; they engage the viewer and inspire deeper thought. The sheet of notebook paper shockingly reminding us of what a 12 year old girl is. The broken lollipop or the crumpled clean white page conveying besmirched innocence. The repetitive writing of Lolita's name giving us insight into Humbert Humbert's obsessive brain.

The following photographic illustration (one of my favorites in this series) could be the view of the deranged Humbert lying in bed staring at the ceiling, and it could also be the panties of a 12 year old girl. A very powerful use of imagery by Jamie Keenan.

Could this image have been as effective if it was painted by a talented artist? I doubt it. Crimped by the intent of the artist, a painting would look too much like either panties or a ceiling. The objectivity of the camera gives this image its double entendre, and it gives us the shock when we realize what our mind is seeing.

If anyone can suggest more effective representational paintings or drawings of this book, I would welcome them. Absent that, I think these images are strong evidence for the argument that the end justifies the means in illustration, and that excellence can extend beyond hand drawn or painted images, to encompass some kinds of photography, graphics and digital imagery.

102 comments:

There’s a double standard in literature and art. Authors can wallow in human depravity in ways no artist would dare, and the literati will lap it up. The rat in American Psycho, the murders of children in Lord of the Flies and Toni Morrison’s Beloved, various scenes in Cormac McCarthy’s work. All fair game in written form, career suicide for a qualified painter.

Lolita spends a nauseating amount of time indulging in the poesy of a pedophile rapist. So much so that any cover not focused on directly sexualizing Dolores, while also playing up her youth, would be way off brand. But, as with the other cases, illustrating that with the full artistic toolbox of a qualified illustrator would be morally criminal. It’s no wonder no one bothered to try it.

To me, it seems that the relative success of the abstract covers over the representational ones is more about artistic self-censorship among the illustrators rather than anything inherently valuable in the work of the graphic designers.

I agree that Jamie Keenan’s cover is the best, but only because he discovered the only socially acceptable way to illustrate a youth's genitals. Which is, unfortunately, probably the best subject matter for the cover of this feted bit of degenerate fluff.

Third from the top is an 1878 painting by Fedorico Zandomeneghi, purloined for the book adding an unwholesomeness narrative not intended by the artist

Bill

I think you've hit the nail on the head, other than artists/writers can deliberately choose how and where they intend the audience to take part in what they're portraying. A terrible event can occur in a story or scene in a documentary or tragic manner, but we've all seen films where the director/writer took a horrific assault and tried to put it to sick use it as a kind of erotica.

Have never read this, so don't know where the participatory intent of the author lay or leaned, but its wider cultural 'brand' has certainly veered into fodder for the warped. I don't think its publishers and so on have always been innocent of playing up to that dark gallery.

Bill

(Some comments are disappearing, by the way)

In response to "Some comments are disappearing, by the way." Thanks very much for alerting me. I never, ever delete a message here unless it's something like an advertisement for escort services in Malaysia. Any time you see a message here saying "comment deleted," it's always by the author, who is usually correcting a typo or changing a phrase.

I checked just now and found that Blogger had sent 3 comments to the spam folder for reasons I cannot begin to fathom. They must've "improved" their algorithm again yesterday, but I have now released all 3. Thanks for keeping me on my toes.

Sorry about the duplication, the 1st one of mine replying to Richard above can be be deleted. (Bill)

David,

I certainly agree that the book covers you prefer are the better ones for the job.

However, I disagree with your following statement:

I think these images are strong evidence for the argument that the end justifies the means in illustration, and that excellence can extend beyond hand drawn or painted images, to encompass some kinds of photography, graphics and digital imagery.

For a start you seem to be conflating literary expression with plastic expression. But my main push-back is that the theme of Nabokov's book concerns deranged, pathological desire, and its subject is a first person account of an older man's desire for a girl on the cusp of womanhood (a very disturbing and upsetting read btw, for this very reason).

So, although the book's title is the girl's name, Lolita, she is not its essential subject or theme. And it is believing that she is, while being aware of the novel's actual theme and subject, that causes the problem with almost any depiction of the girl at all.

Which is the real reason those illustrations on the first set of examples don't work.

I think the comments focusing on the morality of a character in the book are on the wrong path. In my view, the quality of an illustration is quite separate from the virtue of the person or thing being depicted. (Plenty of people admire Bernie Wrightson's complex drawings of monsters and killers.) I also think it's possible to write books and draw pictures on sexual themes in tasteful or symbolic ways, so I don't think the painted representational covers here are operating at any more of a disadvantage than the conceptual / photographic art.

My argument is that the "conceptual" or "idea" illustrations seem more thought provoking and intelligent, inspiring reactions that are more true to the psychological complexity of the literature. In some ways the name written in childlike penmanship on school paper is more horrifying than the representational paintings could be. Can we extrapolate from this to draw any conclusions about the relative merits of conceptual and representational illustration?

An explicit representational painting would likely be disgusting (rather than horrifying) to everyone (including Nabokov himself) but that merely requires a representational artist to balance the elements the way all artists must (see William Gaines' testimony before Congress regarding where to draw the line on depicting the severed head on the cover of Crime Suspense Stories No. 22.)

Plenty of people admire Bernie Wrightson's complex drawings of monsters and killers

That works because the narratives Wrightson illustrated allowed for a monstrous depiction of the figure. Lolita doesn’t allow for that same relationship with Humbert. The novel requires a sympathetic point of view. This is why the cover, showing Humbert’s monstrous red hands painting Dolores's feet, feels so out of place compared to the others. That cover would require a different novel.

I also think it's possible to [...] draw pictures on sexual themes in tasteful [...] ways

How exactly would you suggest an artist should draw a picture sexualizing a child in a "tasteful way"?

I agree with your conclusion David. I think an attempt to illustrate the main characters on the cover of a novel is a huge risk, given how jarringly the visualisation of the character(s) might conflict with the reader’s own. I’d rather not have the book try and show me what the main character(s) look like at all. It feels like a cheap, pulp-novel thing to do.

Personally, I prefer novel covers with some nice typography and semi-abstract graphic shapes which hint at the novel’s contents as subtly as possible. Don’t know if you have the book ‘Mid Century Modern Graphic Design’ by Theo Inglis, but there’s a double page spread of covers by Alvin Lustig from 1943-50, which are excellent examples of unobtrusive, minimal, graphic cover design.

Interesting comments, it seems (to me) that the conceptual designs removes the viewer from the natural disgust one feels towards Nabokov’s protagonist. None of the representational covers work because it sugar coats what the reader will find within. But this is true for many crime novels, look at the covers for, “In Cold Blood.” “In this late stage pretty sure that anyone buying, “Lolita”, knows what they’re picking up.

David: "Plenty of people admire Bernie Wrightson's complex drawings of monsters and killers"

All the great artists create an aesthetic dream world of their own invention. Wrightson's works are obviously fictions, exaggerated and comical; brush-strokes, composing, handwriting, and other clues to human creation evident all over the place and from the ground up. It is art that looks and feels like art. It isn’t photorealistic/hyperreal. It isn’t literal.

Also Wrightson’s work and sensibility don’t promote “interestedness” in the Kantian sense of stimulating the base appetites. (Fear and humor are not appetites.)

Richard: "the narratives Wrightson illustrated allowed for a monstrous depiction of the figure. Lolita doesn’t allow for that same relationship with Humbert. The novel requires a sympathetic point of view."

Wrightson’s Swamp Thing is both monstrous and sympathetic. But it’s only monstrous outwardly. So there is irony, but no actual moral ambiguity. Lolita is morally dubious in its sympathies because HH is monstrous internally, thus in intent and action.

Meanwhile, Lolita also falls into the category of works that titillate while pretending to simply narrate. Like every supposed exposé on tv, it plays a double game of critical observation and prurience. Which collapses the use/reference distinction.

It is touted as a comic novel. Comedy holds nothing sacred. And for good reason; to burst the pompous bubbles of holier-than-thou types by going after their sacred cows under the guise of joking. After all, in politics any given unassailable piety usually masks some kind of grift or crime hidden beneath the cult-like defense behaviors. (Politics is always nestling into religious clothing by forming cults around a scam.)

But there are sacred things which are not cult-related. Which are not political in the religious sense, or related to scams. To me, at least, childhood qualifies.

Like every supposed exposé on tv, it plays a double game of critical observation and prurience.

I’d go further—

Most "comedies" today, including Lolita, operate in a pseudo-critical mode. Regardless of the artist's intent, audiences take them at face value, laughing in agreement rather than in derision. They might as well be clapping. Humor has become a truce word, allowing artists to endorse anything so long as they claim to hate it when the newsmen sit them down for an interview.

Theo Von’s racism parody attracts genuine racists. Larry David appeals to amoral curmudgeons. Female comedians joking about promiscuity draw fans who embrace that lifestyle. Porky's resonates with misogynists. Jokes about hating kids normalize the sentiment.

As for Lolita, the second half of the book seems to exist only to excuse the first. It’s no accident it was originally published by a French pornographer.

Richard, I can't agree with you that all jokes are endorsements of a kind. That's tantamount to the Maoist position that all art is propaganda, so you better propagandize for the Utopia or you might end up dead, you capitalist pig. These literalists cannot understand poetry/figurative language.

Comedy has been edgy since the dawn of time. The 'edge' being the nebulous zone between wrong and right, awful and proper, distorted and true, unsayable and sayable, etc. Which valences are all determined by social methods, bottom up as well as top down, emergent as well as astroturfed.

Blazing Saddles is full of sendups of racist jokes and racists that can be taken by simple maoist brains - (self-righteous politicized people who tend to have both febrile neuroses and reading comprehension problems) - to be actual racist jokes. No cultural product should be tainted by its dumbest interpreters.

Black comedy rooms are full of race-based humor, not just about whites, but also about blacks. It's all in fun. To be offended, one must be taught to be offended. Which is just what is being done en masse by the moral midwits of marxism.

The main error is thinking that jokes with a critical edge are hateful. That's a snowflake take that will and does destroy not only all comedy, but all art and fun as well. No thanks.

When you watch a gaggle of comedians ribbing each other, race gets thrown into the mix all the time. And those people are better, tighter, more loyal friends than any of the activist white ladies with performative black friendships crying about racism at every turn who wouldn't walk alone through a ghetto on a bet.

Regarding the designs, my opinions... the walls-suggesting-legs (last example) is very clever and subtle. The broken lollipop as the 'o' in Lolita though, is the most dynamic and expressive in relation to the content. Also clever, scandalous/gross even in its evocation of menses by the use of the splattered red lollipop. The rest of the designs are nondescript by comparison and I agree the illustrations are all poor for the reasons already argued and others.

Since I don't equate all designed visual communication with "illustration", I can't agree with your anything-goes-in-illustration point of view. Anything goes in book cover design, that's for sure. Anything can be used to graphically suggest the content of a story that's under a particular cover. In house, these kinds of covers are generally called designs, not illustrations. Or simply covers.

I guess the question goes to the definition of the word "illustration." Howard Pyle taught that it meant both "a making clear" and "a making illustrious." It was also presumed to be hand made, rendering a dramatic moment from the narrative.

Design, on the other hand, has always been more abstracted. More graphic yet less clear, less narrative, less hand-made, less illustrious. More coded really, thus more in need of interpretation.

Kev Ferrara-- I think Howard Pyle is a good reference point (as usual). Pyle illustrated fiction stories, historical scenes and fairy tales, but he also embraced the future with an open mind, steering his students from wood engraving to photoengraving to reliable full color. How do you think he would react to a world where all the fiction magazines had died out and illustrators were called upon to illustrate magazines like Psychology Today and Scientific American using "idea" art?

In the present case, we are dealing with a psychological novel about a cultured but spineless academic who becomes obsessed with a young girl and gradually deceives himself into committing monstrous acts-- not just whatever he does with Lolita, but marrying her horrible mother to get close to Lolita, murdering the suitor (another adult) who takes Lolita away, debasing his life and groveling before Lolita, who comes to realize that she has complete control over the adult. (Dorothy Parker described Lolita as "a dreadful little creature, selfish, hard, vulgar, and foul-tempered."). Tell me how a representational illustrator such as Pyle could do justice to such a complex topic?

The concept illustrators are able to depict obsession by writing Lolita's name over and over again (similar to "All work and no play makes jack a dull boy" in Kubrick's "The Shining."). They can crumple the virgin white paper on the spot where her name is handwritten in pencil, to show how she has been besmirched. These and the other concept illustrations impress me as valiant efforts by creative minds to come up with images that evoke substantial motifs from the book. They are trying to deal with the subject matter in a way that a hand painted portrait of a young girl could not.

You say that in Pyle's day, illustration was "presumed to be hand made, rendering a dramatic moment from the narrative" but if Pyle today found those tools inadequate for an effective job, don't you think he would bless these modern tools?

"if Pyle today found those tools inadequate for an effective job, don't you think he would bless these modern tools?"

Pyle saw funny animal cartoons - then one of the hot new things - as an abomination against the beauty of nature. He spoke against allegorical art, saying there had only been a small handful of tolerable works of that nature. So I can't say how he'd react to these newfangled conceptual photo covers. I don't think he believed that all novels required illustrations.

I think I've already agreed that these "valiant" and "creative" conceptual designs are more appropriate as book covers than the figurative illustrations that have been used. And any that could be used. Federico Infante's awful surreal-figurative interior illustrations - the only interior illustrations attempted for the novel in its history - demonstrate what didn't need to be; that the less said visually the better, even if what is said is gibberish.

What is there to draw anyway? There is nothing to be made illustrious in the story. Which explains why the original editions of the book had only type on the cover. Because NOT making clear what is going on is the better strategy.

Of course lollipops, lipstick and panties sell old scandals better than mere typography. So there you have it.

To review a previous point. The elements the designs are built of are ready-made symbols. They are combined in text-like ways to suggest meaning, not in aesthetic ways.

"I can't agree with you that all jokes are endorsements of a kind. That's tantamount to the Maoist position that all art is propaganda, so you better propagandize for the Utopia or you might end up dead, you capitalist pig. [...] Comedy has been edgy since the dawn of time."

Let me clarify the change I'm referring to.

I believe there was a time when humor was mainly derisive or critical. The clown was a fool, and everyone agreed. We laughed only at him, not with him. Humor was a very unchristian way to highlight anothers' follies or vices. We never laugh with Aristophanes's or Juvenal's characters. Voltaire ruthlessly mocks Candide's optimism from a distance. Nast's caricatures are uniformly mean-spirited. Mad Magazine laughed at people. It was a very different time.

From writings dating back to Ancient Greece, most discussions on laughter similarly focused on scorn and mockery.

Aristotle's conceptualization of comedy, we are told by contemporaries, is:

“(as has been observed) an imitation of men worse than the average"

Socrates/Plato explains that laughter is the act of indulging in phthonos, or malice.

Hobbes explains:

“Laughter is nothing else but sudden glory arising from some sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others”

They formulated humor this way because people still consumed comedy that way. They weren't wrong, rather, their anthropology was specific to their time/culture.

We still see this strange older kind of humor leak into the media of the old. For example, Saturday Night Live still loves to laugh derisively. It's disgusting, but apparently there is still some minority who like that sort of thing.

But of course this sharply contrasts with modern humor. When a comedian self-deprecates about their foolishness, we laugh only if we see that same foolishness in ourselves. Who would be so sick to laugh at another in direct scorn? Sociopaths, basically.

Modern humor is about mutual understanding. Yet, I'm suggesting, it still play-acts as this older derisive form, even though that form is essentially dead.

By pretending to be derisive, it allows mutual understanding to escape the watchful eyes of the censor. But is racism funny "scornfully"? No, we don't laugh at the racist the way a 19th century man laughed at the clown. We laugh only when we believe that there's secretly some nugget of truth in it, and we self-identify there -- white guys really can't dance.

"but he also embraced the future with an open mind, steering his students from wood engraving to photoengraving to reliable full color"

More that photoengraving reproduces the work, whereas wood engraving (when the illustration wasn't tailored specifically to the technique as an aesthetic choice) either visually translates or makes something from it that paraphrases the original, I think ?

The possibilities of new methods of colour reproduction must have very exciting, but the issue is still one of reproduction something painted or drawn. Is it not better to see these things as comparable to musical performance and recording technology (as it advanced) ?

Bill

Kev ferrara wrote: "The elements the designs are built of are ready-made symbols. They are combined in text-like ways to suggest meaning, not in aesthetic ways."

It should not be surprising that so much art is inching into curation of "ready-made symbols" these days. There are billions more images today than in Howard Pyle's day, and our ability to access and make use of them has increased a thousand fold. What hasn't already been done a hundred times? And who doesn't recognize traces of previous images being used (advertently or inadvertently) in new images? Fine artists like Warhol, Richard Prince and Koons have ended all pretense as they openly steal ("re-purpose") other work and suffer no consequences. Even the educated audience for this blog is constantly saying, "this illustrator was influenced by X or stole that idea from Y." In the comments to this post, Anonymous/Bill was quickly able to identify a cover to Lolita as lifted from an "1878 painting by Fedorico Zandomeneghi."

That's why I found it so interesting to hear from Metz about the October cover for The Atlantic. He was not hiding anything; he creatively melded ready made symbols from Pinocchio, Dumbo, Ray Bradbury's evil circus, a Victorian hearse, and other elements that he assumed a literate, knowledgeable audience would recognize, and he assumed their recognition would broaden / enhance their experience of the image (although young and uncultured viewers could equally appreciate the image without recognizing the references.)

I don't understand why you would think this process-- which may be a larger and larger part of our future, as it seems to have both economics and technology on its side-- is not "aesthetic."

"What hasn't already been done a hundred times?"

Since I'm not big on either low expectations nor artistic eschatology, I'll take the positive view; presumably an infinite number of ideas. Unless you think Art is over? Just like it has been said twenty times before.

"that he assumed a literate, knowledgeable audience would recognize, and he assumed their recognition would broaden / enhance their experience of the image (although young and uncultured viewers could equally appreciate the image without recognizing the references.)"

Yes, this is literary thinking; a codified lexicon. Postmodern thinking even, because being derivative is encouraged. The language relies on associations and symbols already well established to the point of rote, if not cliché. These symbols are literally given to design students in books that are equivalent to dictionaries.

Putting together these ready-mades to express concepts is the new glyph text of our post-literate/post-literature age. The meme as art, design, and literature all rolled into one lite bite.

Richard: “Modern humor is about mutual understanding. Yet, I'm suggesting, it still play-acts as this older derisive form, even though that form is essentially dead.”

There is always a point of view to attack any position, any personality, any belief. And comedy always has a point of view, which necessitates that it is relatively opposed to something of a different view. Thus comedy is always opposing if not outright attacking something in some way. No?

Ask the opposite: What is the funniest sincerely nice thing that has ever been said? What is the funniest charitable depiction of normalcy?

Anonymous/Bill-- I agree that wood engraving could only "paraphrase" the original, but its goal was to get as close to being the original as possible under the limitations of the time. There were no medals being handed out to wood engravers who tried to add their own style and embellishments to the original.

Pyle said to his students, "I know there is no reliable color reproduction now, but you need to train to use color because one day-- during your lifetimes-- printers will be able to reproduce color well." In my view, the new freedom to use color in illustrations was more than the equivalent of improvement in recording technology. Perhaps it's more like the invention of the piano to replace the harpsichord. Suddenly the increase in powers-- the increased range in volume, the ability to sustain a tone for longer periods, the greater sensitivity to the notes played, ushered in the romantic period in music, following the classical period.

Kev Ferrara wrote: "Federico Infante's awful surreal-figurative interior illustrations - the only interior illustrations attempted for the novel in its history"

Agreed, they are truly hideous, although most figurative illustrations today seem to be. Why, after all this time, would the publshers of Lolita waste their time on an illustrator like Infante?

"What is there to draw anyway? There is nothing to be made illustrious in the story."

A dozen things. The forlorn and twisted Humbert Humbert standing isolated from the world. Lolita's loud and shrewish mother. Humbert with the gun planning the murder of the man who took Lolita away. Lolita's coltish, spindly legs that would've caught Humbert's attention, sticking out from under her schoolgirl skirt. Don't say there was nothing to illustrate; think of the brilliant film about child molestation, "M" with Peter Lorre. The tragic scene with the little girl's balloon drifting away was inspired. My point is that none of those traditional types of figurative illustration could get as close to the heart of the message of Lolita as the conceptual images I've shown.

Ask the opposite: What is the funniest sincerely nice thing that has ever been said?

As far as I'm concerned, every actually funny thing that has ever been said about someone else falls into the category of either kind or, at worst, neutral, so I'm not following your argument. If a joke is unkind, it's only funny when it's self-directed. Otherwise, you just sound like a pathetic asshole like Rickles or Carlin.

Yes, but I'm not sure how the comparing of improved fidelity in methods of reproduction to a conceptual graphic (idea art) - or c.g. or the type of digital art that knits and melds pre-ready pieces together in a collage/frankenstein manner - comes in.

Both bypass ideas of an illustrator as it was understood, 'idea-art' would have cognates in some kinds of symbolism they could relate it to, but I think a 19th c-born artist (and probably the entirety of their contemporaries) would demand that it was transfigured into an aesthetic design and they wouldn't have seen the covers above as such (obv. some people today might)

Bill

Richard, you'll need to enlighten us regarding what you think is funny. Because one wouldn't want to be considered a fan of "pathetic assholes" in running afoul of your elevated sense of humor and decorum. Do share some examples.

And 'the range of the piano' was already there in what the artist could make, and the technological advance Pyle was seeing and predicting was just in the ability to reproduce it, no ?

And the other 'technological advances' that I think you're alluding to in "the end justifies the means" in illustration (you've mentioned the Atlantic cover, and in the context of two of the recent posts) aren't really related to this.

As for that assertion - I don't think that the "ends" - the results we've been looking at - succeed in justifying anything. I don't think they're successful.

Because we observe things in a certain way, our eyes move around the contours of those autumn leaves that are hanging everywhere at the moment, their inclination, their tilt and colour are explored with the mind-eye as we look at them, with all the suggestions and associations operating concurrently to this, just to give an example from the window now.

When somebody draws or paints this, by hand, it's not only that the process is analogous to this kind of observation, but that it's a sub-category of the same phenomena of participation. And is very close to it in the way it proceeds - the curve your eye moves along (out there in the world or in the inner world that's intimately related to it) is on a continuum with the one your pencil tip traces. When colour-tone you place on paper meets the same pitch as the one you see, there is a tangible merging like notes meeting in unison, two bells across a valley, the combinations are like chords, and as most illustrations are composed of figurative elements + narrative + archtypes + cultural resonances, and the same processes are at work in these, the whole thing is very symphonic. Even when the illustration is of inward things, memories or imaginations, the tempo is like that of walking through a landscape in physical movement and the thought and feeling that happens in tandem and how this is similar to viewing one.

When a viewer later sees a picture, the whole things recurs and is recognisable to them in the work (in a way work produced by 'tech' substitutions isn't) as it's a common, human process.

Here we're just talking about seeing the original work; or as far as 'technical' goes, in terms of how this is successfully reconfigured by the fidelity of the reproduction.

But the other 'technical' that's been mixed in here is the kind that tries to 'short-cut' the process. There are tools that operate in simulation of the traditional ones. But why ? Especially when the results, I think, are inarguably inferior (I'm referring to psudo-brushes and so on, making lights on screens vs pigment on paper, which has a sense relation to real experience that the first doesn't).

The further kinds of 'tech' production short-cut things still further, not only in thae artificiality of the elements they use but in that the manner they produce is alien to and un-analogous to how the ways sight, imagination and contemplation work, how they combine in how a person paints or draws, and how this it recurs in a viewer. They relive it.

The mistake comes from thinking that picture-making by the spirit-organism human being is analogous to the artificial substitution that informs the kind of modelling envisioned by VR. One is a fractal of reaity - the physical and the quality-world, the other is a substitution for it.

And you feel it in the respective results.

Bill

>>"Lolita's coltish, spindly legs that would've caught Humbert's attention, sticking out from under her schoolgirl skirt."

You think erotic pedophilic depictions are a good idea?

The "heart of the message" indeed.

~ FV

>>>"Lolita's coltish, spindly legs that would've caught Humbert's attention, sticking out from under her schoolgirl skirt."

?? You think er0t1c ped0ph1lic depictions are a good idea?

The "heart of the message" indeed.

~ FV

"A dozen things. The forlorn and twisted Humbert Humbert standing isolated from the world. Lolita's loud and shrewish mother. Humbert with the gun planning the murder of the man who took Lolita away."

I thought the whole point you were making is that psychological books shouldn't be illustrated figuratively?

Something seems off to me about usurping the visualizations of characters in certain kinds of literature. I would think readers would want to do that themselves based on the descriptions provided.

Howard Pyle taught his students to illustrate interstitial moments, the moments between what's been described, implied by what has been described. That way they weren't reliant on the text, and weren't redundant with the text. So the illustration would be an additional contribution and would stand on its own.

Kev ferrara wrote: "I thought the whole point you were making is that psychological books shouldn't be illustrated figuratively?" That's close, but what I was actually trying to say is that conventional figurative illustration is at a severe disadvantage when it comes to doing justice to psychological books. It can be done. One of the best, IMO, is Phil Hale's series of covers for Joseph Conrad's profound psychological novels (you can see his covers for Lord Jim and Nostromo here: https://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2013/01/delaware-exhibition-phil-hale.html ).

You asked, "What is there to draw anyway?" The examples I gave you were the kinds of scenes that would've been selected by illustrators in the 1920s - 1950s, and some of them (such as visually emphasizing the isolation and alienation of Humbert) would be OK. I just don't think they would convey the themes of the book as well as the concept art approaches shown here.

Anonymous / FV wrote: "You think er0t1c ped0ph1lic depictions are a good idea?"

I don't think the words of the book were intended to encourage pedophila and i don't think drawings of "spindly legs that would've caught Humbert's attention, sticking out from under her schoolgirl skirt" will turn anyone into a pedophile. Paintings of jewels don't turn people into jewel thieves.

It should not surprise you that more than one cover of previous editions of Lolita did show "coltish, spindly legs." (see, e.g.,https://www.dezimmer.net/Covering%20Lolita/slides/2005%20US%20Random%20House%20Audio,%20New%20York.html ) and no, I don't have a problem with that. I would imagine they freak some people out with the enormity of the crime. I would imagine some people would say, "I can begin to see the aesthetic of people like Humbert," just as they might say, "I can identify with the sense of power of the rapist or murderer on the the cover of that detective novel," but that doesn't turn them into a rapist or a murderer. If I was looking for reasons to censor illustrations, schoolgirl legs would be 257th on my list.

>>>>"I don't think the words of the book were intended to encourage pedophila and i don't think drawings of "spindly legs that would've caught Humbert's attention, sticking out from under her schoolgirl skirt" will turn anyone into a pedophile. Paintings of jewels don't turn people into jewel thieves."

What is the purpose of an image of the girl's legs? It is ogling or else it has no relation to the story.

To ogle the girl's legs is to put the viewer in the position of the ped0ph!le. Who else in the book is looking there so intently? The Point of View is clear simply from your description and the nature of the book.

Point of View shots cause identification between audience/artist and the character. We see the legs through the ped0's eyes or else there's no point to the illustration.

To see through the ped0's eyes IS to find those child's legs attractive. That's why he's looking. And if the drawing doesn't attempt to do that, then it really ISN'T illustrating the ped0's subjective Point of View. So why is it there?

If it is somehow objectively done, with no desire expressed, then what is the purpose of the illustration in the first place?? Why include that? We know what that looks like.

So either the illustration you suggest is itself a surrogate immoral act, a kind of pornography. Or it is some objective random peek at some girl's legs which has nothing to do with anybody's point of view in the story. A bad idea either way.

~ FV

David "One of the best, IMO, is Phil Hale's series of covers for Joseph Conrad's profound psychological novels"

Those Hale paintings are no more Nostromo illustrations than Zandomeneghi's painting was a Lolita illustration. They can work for a thousand other novels, and will actually illustrate none of them.

Which led me to realize that all the graphic design solutions for Lolita are basically typographic solutions but the last one. And graphic design/typographic solutions are very malleable in meaning.

All the typographic solutions can say many other things and work fine: The lined paper can say "My First Crush" at top. The crumpled paper can say "The Snows of Kilimanjaro". The lollipop one can say Lollipop Murders with the actual lolly playing the 'o' as it is now. The dark shoe can be any murder mystery. The two socks can be part of the word 'Laundry' instead of Lolita. Anybody's name can be obsessively written a hundred times. And the last one of the leg walls can be called "I Dream of Jeanie."

The point, again; these are design solutions. Not illustrations.

Kev Ferrara-- I understand your puzzlement. The name "Nostromo" isn't painted on his forehead.

I think your distinction between "design solutions and illustrations" is a false dichotomy. You were closer the first time when you cited Howard Pyle 's teaching that illustration is both "a making clear" and "a making illustrious." I think those conceptual illustrations do both-- certainly better than the representational illustrations. I'm not sure of the utility of your exercise in the "malleability" of the images. All art that rises above the level of a schematic diagram has some inherent ambiguity. But if you want to page through Howard Pyle's "Book of the American Spirit," you could perform a similar exercise: are these colonialists standing around for a religious ceremony? A war council?

are they opening a new road? Planning the first Thanksgiving?

David: "I understand your puzzlement. The name "Nostromo" isn't painted on his forehead."

Heckles can stun and stand opponents down. The best defense is a good offense. Unless you're talking to the intelligent. Then only a simple clear correct argument will suffice.

"You were closer the first time when you cited Howard Pyle 's teaching that illustration is both "a making clear" and "a making illustrious." I think those conceptual illustrations do both-- "

They do neither. That's the point. Photos and typefaces are generic modular symbols. Too generic to relate to anything in some integral way or to be considered illustrious. However, I agree that the cover memes you selected are better than the representational illustrations for selling the book. For reasons already stated.

"But if you want to page through Howard Pyle's "Book of the American Spirit," you could perform a similar exercise: are these colonialists standing around for a religious ceremony? A war council?

are they opening a new road? Planning the first Thanksgiving?"

You will find that Pyle's illustrations correspond to the scenes in the book that they illustrate. Should you need more help aligning the one with the other, there is usually a bit of text information beneath the images that can add further direction.

>>>>"And graphic design/typographic solutions are very malleable in meaning. All the typographic solutions can say many other things and work fine: The lined paper can say "My First Crush" at top. The crumpled paper can say "The Snows of Kilimanjaro"."

Are you saying that because changing what is written in the typography so easily changes the meaning of the visual elements or photographs or alters what they refer to that its all really design and not an illustration of the story within? If it really illustrated the text, that wouldn't happen?

And this would apply to the Phil Hale Nostromo covers because if you only changed the title to something like "The Lost Weekend" or "A Personal Storm" nobody would bat an eye? It fits just as well.

But aren't we dealing with five different things here? There's the photo of the wall (maybe that's digital?), there's the typography, then the text the typography says, then there's the isolated photographed elements (the lollipop, the socks, the shoe, lined paper), and then there's the weird Hale paintings? What's the connection that makes them all design and not illustration?

~ FV

FV: “Are you saying that because changing what is written in the typography so easily changes the meaning of the visual elements or photographs or alters what they refer to that its all really design and not an illustration of the story within? If it really illustrated the text, that wouldn't happen?”

Yes.

I'd say the difference between a work that actually illustrates a story versus one that is only associated with it by editorial fiat is just how specific the unified narrative/aesthetic/poetic effect is to an actual moment within the text as against any other moment in any other text.

That which is composed in a modular way - necessarily of generic elements - can never be either as integrated nor as specific in its visual references. Which is why text content is necessarily used to frame and direct the imagery as related specifically to the story.

The type is telling us, not showing us, that the imagery relates to the story. Whereas an Image shows us.

I should point out; “generic” doesn’t refer to blandness, but to a level of aspecific abstraction. In Taxonomy it would be equivalent to Genus or Species. Any modular unit that can be used in a typographic design is essentially functioning at the level of Genus or Species. (Whereas illustration shows us, for example, a specific fictional dog that corresponds to a specific fictional dog in the narrative.)

Phil Hale’s paintings, while they are obviously specific works of art, are not specific works of illustration. As scenes they too work at the taxonomic level of Genus or Species.

>>>>>>>>"That which is composed in a modular way - necessarily of generic elements - can never be either as integrated nor as specific in its visual references."

What do you mean by integrated?

~ FV

I had always assumed that the Phil Hale cover for Conrad’s Nostromo was a pre-existing painting he had made as part of a personal series, not made specifically for the novel, given that the clothing is modern and the novel was written in 1904.

Laurence John-- Actually, Hale read all seven books by Conrad before he started work on the series of covers. His cover for Typhoon was the most literal of all the covers. You can make out the mad captain McWhirr shoveling coal, stoking the steamer as his ship sails into the heart of the typhoon. But Hale also felt that Typhoon was the most "unfinished" of the covers and would've benefited from another sitting.

Hale reports that all of the covers were of actual scenes from the books, but the more he worked on them (and the happier he was with them) the less literal they became.

FV: "What do you mean by integrated?"

The more relations holding elements together, and the more suffusive, wedding, and encompassing those relations, the more unified or interwoven the elements. Thus the more difficult to swap them out or change them, or lose them or add others.

Naturalism alone, in terms of portraying a particular event moment in a believable setting, has an overwhelming number of required relations. Imagism (with a pictorial idea as the governing concept) on top of naturalism adds many additional relational/integrative layers besides. Any element, by the time it has been integrated into a poetic and naturalistic image – which is simultaneously a narrative, a shaping, an orchestrating, a thematic, and a kind of marinating process - is no longer modular, even if it once was.

Whereas typo-graphics, as in these mass market literary meme-covers, are built of conventional ready-made symbols chunked together in basic text-like ways. (Text being the most modular, stylized, and conventionalized form of communication. The opposite of naturalistic.) All of it can be hot swapped on a moment’s notice. Every typeface in all thirteen of these covers works. How can that be? From the gothic, to the classical serif, to the 50s Latin wedge-serif, to the formalized script, to the handwriting. And there are a thousand more styles that would also work. And you can switch from one to another in a layout program with the click of a button.

Look at the socks used for the ‘L’ and the ‘o’. Do we even understand them to be Lolita’s - whoever that might be? I think the socks are clearly understood as being generic design elements by the audience. Prepped by prop handlers, lit and shot in a pro studio. Nobody thinks they’re actually Lolita’s socks. Because they aren’t fictional socks of a fictional girl in a fictional situation. They’re just store-bought girl’s socks, shaped for the photoshoot for a pre-ordained typographic design. Would it matter if they were changed somewhat in shape? In color? In style? (Nope. Not really.) Could the exact same socks be part of a type treatment for a different book entirely? (yep.)

The larger philosophical point is that the modularity of symbolic communication is inherently disintegrative.

"Hale reports that all of the covers were of actual scenes from the books, but the more he worked on them (and the happier he was with them) the less literal they became."

Hale's trying not to confess that everything in the paintings that wasn't part of his reference photos of himself melted away as he worked. Presumably, if he hadn't held the shovel in the Typhoon photo, Typhoon too would have ended up seeming like a random personal impressionist painting based on a photo, instead of half an illustration.

Spotlit poses aren't pictorial or narrative ideas. Find any photo of a fireman/stoker/boilerman on a steamer of the era and you'll see that Hale never found out about what he was painting. Or what was meaningful, intense, and visually striking about the job and its setting. Coal all over the place, sooty and sweaty metal machinery closing in, the fire in the boiler itself...

Additionally, here's how Conrad described McWhirr in the second paragraph of the story: "His hair was fair and extremely fine, clasping from temple to temple the bald dome of his skull in a clamp as of fluffy silk. The hair of his face, on the contrary, carroty and flaming, resembled a growth of copper wire clipped short to the line of the lip; while, no matter how close he shaved, fiery metallic gleams passed, when he moved his head, over the surface of his cheeks. He was rather below the medium height, a bit round-shouldered, and so sturdy of limb that his clothes always looked a shade too tight for his arms and legs."

Presumably, then, the cover is not of McWhirr at all. As well as not actually taking place on a steamer ship of the era.

Not coincidentally, Hale has said (in various wordings) that as an artist he reserves the right to be meaningless.

Haha. I think you've gone a bit too far there, Bill. Jeez.

Poor Kev... the modern world must seem a mystifying place to someone with such cast iron standards.

Where there's a trace of ambiguity about the subject of a Howard Pyle illustration, we can rely on "a bit of text information beneath the images that can add further direction" but heaven help us if any text should stray within the four corners of the picture because that disqualifies an illustration into "mere typography" or " text-like ways to suggest meaning, not in aesthetic ways."

Joseph Conrad was an author who was very much a part of that puzzling modern culture. His story, "The Secret Sharer" was on the surface about a stowaway on a ship, but who turned out to be a non-corporeal psychological other self. Pretty tough to illustrate that (assuming you read all the way to the end).

Which brings us to Typhoon-- a story about a stolid, unimaginative sea captain who refused to alter the course of his steamer one degree even though he put the lives of everyone on board at risk. He was alone against the storm, which had a wind so powerful "it isolates one from one's kind." I can easily see an illustrator depicting this theme as a lone individual putting his shoulder to the effort; it's more a psychological battle than a meteorological one. You seem concerned that we can't see the captain's red hair in a storm at night, and we can't tell if the steamer is genuinely "of the era." I'm guessing that both Conrad and Nabokov would tell you that you're barking up the wrong tree, but to each his own.

"Poor Kev... the modern world must seem a mystifying place to someone with such cast iron standards.

Cute turn. While it is true that I can't lay claim to your thermoplastic standards, having a deep sense of semiotics does demystify various interesting communications quite effectively.

"Where there's a trace of ambiguity about the subject of a Howard Pyle illustration, we can rely on "a bit of text information beneath the images that can add further direction" but heaven help us if any text should stray within the four corners of the picture because that disqualifies an illustration into "mere typography" or " text-like ways to suggest meaning, not in aesthetic ways."

You're confusing things. Pyle's pictures illustrate the text and tell a story unto themselves. They are not ambiguous in the sense that Hale's paintings are. (Though I admit I was amused by your attempt to be willfully mystified by them to "prove" a nonexistent similarity on that score.)

I only mentioned the text below Pyle's pictures because (as I wrote) they can lead you to the pages where you may read the text that is illustrated, should you desire more information.

Although Pyle advocated for illustrating interstitial moments in the text, so the illustrations would not be redundant with it. So in reading the text, you will find Pyle's pictures between the lines, not in them. Yet all the details, characters, moments, and settings are present in them as in the text. They run parallel to the text. Nothing in them runs perpendicular to the text, causing some disjoint.

I'm not going to re-explain the typographic points, but it does seem others were able to understand me.

"I can easily see an illustrator depicting this theme as a lone individual putting his shoulder to the effort; it's more a psychological battle than a meteorological one."

Yes, that is "easy to see." However, illustrating a mood or a state of mind doesn't illustrate a text. Until enough other narrative information in the picture runs in parallel to the text to set the correlation. Otherwise the picture is only an "illustration" by editorial fiat.

"You seem concerned that we can't see the captain's red hair in a storm at night, and we can't tell if the steamer is genuinely "of the era."

It is hardly eccentric to expect some basic parallels to the text, rather than perpendiculars. The whole conception is wrong. Wrong type of man, lacking not just the hair color but the characteristic facial hair Conrad describes, even the body type. It's not Conrad's Captain. It's a photo of the artist posing.

And as far as the furnace/boiler coal shoveling goes, it's not just not illustrating Conrad's steamer. It isn't illustrating a steamer at all. Look one up yourself. As is, sort of looks like a train if one of the passenger car compartments contained coal.

Asserting that contradicting or ignoring the text is perfectly fine in a book illustration doesn't make it so.

"I'm guessing that (...) Conrad (...) would tell you that you're barking up the wrong tree, but to each his own."

I guess our guesses cancel out. Because I'm guessing it would matter a great deal to Conrad that the illustrator had actually illustrated his book, rather than a moody photo of himself.

David,

As you’ll know, It’s quite common for publishers to use a famous pre-existing work of art on a novel cover. As well as the one mentioned by Bill (3rd comment above), there’s a Penguin edition of Lolita with a painting by Balthus from 1937 called ’Therese with Cat’. Both were painted before the novel existed. You do agree (I hope) that they can’t be illustrating scenes from the book, and therefore they’re not really ‘illustrations’ at all ? (in the correct use of the term ‘illustration’). They link with the books only in a ’thematic’ way.

I assumed the Phil Hale Nostromo cover was a pre-existing painting for similar reasons; although it features anachronistically modern clothing and looks like a typical painting from his personal work, it works in a similar ’thematic’ way. As a ‘mood piece’ rather than a scene from the book. Therefore I assumed (wrongly, it turns out) that it wasn’t an ‘illustration’ in the usual sense (sorry Phil, my bad).

The Balthus one, I'm guessing, shares the sickness of the Nabokov's male protagonist. I don't know much about Zandomeneghi, but I'm going to trust that it was painted with the same intention as the context where it is usually curated as part of - scenes of domestic and family life in the nineteenth century, and if that's the case it's not a pleasant thought to think that that's what's done with one of your paintings (possibly of the artist's daughter ?) after your death.

Yes, paintings and illustrations are reused as covers all the time, Penguin, Norton & Everyman editions of 'classics' and so on. Though Penguin seems to be phasing into using 'mood' photography instead, which I think are poorer than the paintings they formerly used - even as covers (there's no doubt that the paintings are better images than the black and white photos), and this despite the photos being (as far as I'm aware) commissioned specific to each book.

Others might disagree. But I think it shows that there's nothing necessarily wrong with using paintings or visual elements for a book cover they weren't designed for. But can it be called illustration if it's 'mood' or associative in how it works ?

Bill

"I think you've gone a bit too far there"

The Grimm one did remind me of it. It's thoroughly enchanting, you'll agree.

Bill

(meaning, at the end, I think you're right about the illustration 'proper' question. / Bill )

Laurence John-- Yes, I totally agree. There are plenty of pre-existing images whose "concept" is similar to the concept of a later book, especially those concepts about human nature that run throughout every art form for centuries. I have no problem with saying that a picture from 500 years ago "illustrates" a concept in a modern book (and I would say the same about a Phil Hale painting that was not specifically commissioned for the Penguin Classics series but which nevertheless makes "clear and illustrious" (in Pyle's words) the unnerving, eerie, psychologically complex world of Conrad.

"Find any photo of a fireman/stoker/boilerman on a steamer of the era and you'll see that Hale never found out about what he was painting. Or what was meaningful, intense, and visually striking about the job and its setting [....]

Hale has said (in various wordings) that as an artist he reserves the right to be meaningless."

And is there a difference when this is a deliberate choice or results from lack of knowledge ?

"Much of the work that is being turned out to-day [....] is done by young men who are absolutely uneducated, and an illustrator requires education as much as an author; much of it is done by people who are too careless, or too stupid, to read or to understand the MSS. which they illustrate. Thus, in looking through late numbers of a magazine, I learn that all the policemen in New York weat patent leather shoes; while from another I find that when people are very poor in France, they rock their babies in log cabin cradles, cook their meals on American stoves and sit upon Chippendale chairs."

(Modern Illustration, Pennell - 1895)

- pejoratives not aimed at Hale, by the way, just wondering about the question.

For instance, we know images of the Virgin Mary using indigenous iconography, scenes from ancient Israel in medieval european settings, as extent a result of something like the ignorance Pennell's refering to, but also because something of the heart of the matter of the scenes or people illustrated have been integrated into a later spirit.

How much of this should be allowed an illustrator, who transforms elements of the book into his or her own expression, abandoning fidelity to a text ?

How much is Penguin (or whoever) deciding that the contemporary image will score commercially with the moody preferences of a market than will a truthful illustration of a scene from the late 19th or early 20th c ?

Bill

(There is a market for 'classics' among poseurs, many of whom will never even learn that the cover mightn't be congruent with the content of what's on their shelves. / Bill)

Anonymous/Bill-- you and a number of other commenters, such as Richard and chris bennett, can't seem to get past the morality of Nabokov's protagonist. I think the relationship between art and morality is not so simple.

We have examined these questions on this blog in the past. For example, can a bad person make good art? (As I recall, Kev Ferrara cited the example of a good sculptor with Nazi sympathies but I'm afraid I can't recall the name). Wagner is often cited as a loathsome person who composed beautiful music. A second key question: Can good art have an evil subject matter? (This seems to be your concern). And a third question: who gets to decide what counts as an evil subject matter? We've talked here about the Islamic fundamentalists who declare fatwahs to murder artists who draw the prophet, or the Taliban who dynamited the two monumental statues of Buddha carved into the face of a cliff in Afghanistan. They, like you, could not get past the immorality of the art.

A fourth question: How unequivocally must an artist denounce the behavior you believe is immoral? Can Nabokov illuminate the nature of Humbert Humbert without denouncing him in each sentence? In the classic movie "M," Peter Lorre has been exposed as a child molester and is about to killed by the angry mob. He screams that he can't help what he does, that "this evil thing inside of me" torments him and forces him to do what he does. (worth watching: https://youtu.be/jUDUbxsNjV0?si=Nj-dRdk11wya6cEu ). Is the ending of M bad art because it makes Lorre seem more human?

It seems to me that you have a lot of heavy lifting to do before you can dismiss the art of Lolita because of "the sickness of Nabokov's male protagonist."

David: "I have no problem with saying that a picture from 500 years ago "illustrates" a concept in a modern book”

David, you might have misread my last comment. I’m saying that a pre-existing painting ISN’T ‘illustrating' the novel. It’s only sharing thematic content or mood with the novel.

You seem to be using the word ‘illustrate’ in a looser way, akin to ’shares themes with’.

Since you mention the questions of art and morality (that wasn't what I was talking about in the recent comment), it depends - are the immoral or depraved events or characters being used in such a way as for the reader/viewer to identify with them and inwardly enact or take part in these things ? Or are they being used in a different way; such as how, for instance, war may be portrayed without it being a ritual enactment for the spectator to take part in jingoism or bloodlust ?

When it comes to things under the broad manner of ways in which sexual fictions are enacted/presented, the difference in these choices becomes very pronounced - because, due to the forces involved, there is little to differentiate the 'imaginary' participation of the spectator in the fiction from the real-life enactment of these things. Porn is a fiction people who use it take part in. Love-scenes in films are used as porn-lite. So, the author/artist/fim-director is going to be making a deliberate choice about where he wants to situate his audience.

That's where to look for the answer to your (correctly identified, I think) "key question: Can good art have an evil subject matter?"

Richard said, in the case of Lolita, the second half seemed to exist to excuse the first. I have a hazy memory of the Jermy Irons film, and can't remember if it was chronologically split so clearly into these halves, but it did seem to be have this same hypocritical split, pandering to perverts one minute and aloof and interrogatory the next.

As for the book, I haven't read it ( and won't be), but that's irrelevant -

In the comment I was talking about the appropriateness of the images to the text, Balthus' (that Lawrence referenced) I presume was paedophilic (Bathus', ugh, 'speciality'...), the Italian artist's painting - of what I think was his daughter - was put to the purpose of illustrating that sort of gaze.

But anyway, the point being that the conversation as it meanders above has turned on these questions - crap illustrations commissioned for a text and serving it (and decent paintings purloined and co-opted to do so even when they are explicitly contrary to the purpose for which they've been put), the question of whether or not crap graphic elements (or good conceptual arrangements, if beleved to be) that aren't necessarily illustrations do the job better.

Leading on to the deliberate choice of a commissioned artist to renege on the text, vs an illustration that's truthful to the scene and age. And the overlap of all this with generic paintings with varying degrees of appropriateness to the story, or its psychological/symbolic content, or its era.

Etc.

Bill

Holy Hanuman - who are you comparing me to 😃 ?? I missed that on a first read

- Draw pictures of Moe-the-mad-mullah by all means, and the immorality was in the dynamiting of the Buddhas, not in the their creation.

Do you think ethics and morality are real ?

Moe had something in common with Humbert, as it happens....is drawing a picture of him immoral because they say it is, or is marrying a nine year-old or lusting after a twelve-year-old somewhat worse, or do you believe the question to be irrelevant, because of relativisim ?

Bill

(As I recall, Kev Ferrara cited the example of a good sculptor with Nazi sympathies but I'm afraid I can't recall the name).

Arno Breker. Good sculptor, particularly of heads. Hard to find his best work online nowadays, not sure why. The search engines are becoming terrible.

I wouldn't say Breker was great like Michelangelo, Rodin, Bernini, or Szukalski at his sober meso-american-futurist best (Boleslaw, Struggle, Prophet, Flight of the Emigrants, Michelson bust).

I just got 'Superman's petulant twin'

Bill

Bill: "Is there a difference when (erroneous, missing, or faked setting details are) a deliberate choice (versus when they) result from a lack of knowledge ?"

We can only read the intentions of the artist as embodied as physical/expressive efforts in the artwork itself. Claimed intentions that never made it out of an artist's mind onto canvas don’t exist/can’t be verified.

The associative proximity of a work of art to a text determines that it is an attempted illustration of the text. Another physical/expressive claim.

Then: Does the work run sufficiently in parallel to the text, acknowledging it and adding to it? Or is it contradicting the work, ignoring it, diverging or running away perpendicular to it?

It is impossible for an artwork not made to illustrate a story to actually illustrate it in some sufficient, clear, illustrious way. It may do so in some generic way via editorial fiat; which is actually an attempt by the editor to illustrate the story (with another man’s work).

Real works of art are not generic things. Each is sui generis – of its own kind – a story and its illustrations alike. Or else they’re just mindless commercial products; unconscious and insensate.

Hale’s better paintings for Conrad are not generic things. But because they are abstracted, they can be used generically. They don’t locate to any particular story except by fiat/proximity.

Photos never illustrate stories because the person in the photo is not the artist's conception of the writer’s character. The light rays bouncing off real people aren't fictions.

"Hale’s better paintings for Conrad are not generic things. But because they are abstracted, they can be used generically. They don’t locate to any particular story except by fiat/proximity."

I think it *is* possible (certainly permissable) to create an illustration that runs in certain respects what you call perpendicularly. Much as Shakespeare can be presented, but here it is woven with the text, not just adjacent to it, , and very often the decision is made in order to create a superficial frisson from something that is to an extent *not* appropriate to it, ie - for clumsy reasons, usually to excite notice.

I can imagine that this can - and surely must have at one time or another - illuminate things in the text, but it's usually a bad decision, or at best becomes something other than a serving illustration, such as a purpose that is bubbling under the painter's skin that he's used the commission to let loose.

There are lots of little clauses or exceptions you could possible add to both kinds that might seem to muddy this (there is no line that comprehensively seperates the 'serving' aspect from an artist's original input when illustrating, I think), but I think what you say (if I get you correctly) is broadly true

Bill

Laurence John wrote: "David, you might have misread my last comment. I’m saying that a pre-existing painting ISN’T ‘illustrating' the novel. It’s only sharing thematic content or mood with the novel."

No, I think I read your comment correctly. It's just that I agreed with your first part (that pre-existing works are often used for the covers of books) but not with your point that such pictures could not qualify as illustrations of the book.

Let's assume there are easily a thousand paintings of a man and a woman in a romantic clinch, and a thousand books containing a scene with a man and a woman in a romantic clinch. If the "theme" or the "concept" of both is romance, I don't understand why a painting depicting that theme cannot serve as an illustration for the book. Obviously, a painting of modern urban romance would be a misleading cover for a medieval romance, but assuming there were no glaring discrepancies in costume or time period, a great picture of a passionate romance that pre-dated the book could be perfectly suitable, I think. A book about hell could be illustrated by Hieronymus Bosch and a book about war could be illustrated by a Goya etching. Show me the rule that says otherwise. I'll go with Pyle: if the picture conveys romance or hell or war in a clear, illustrious way, that's good enough for me.

I don't go looking for the date of manufacture on the boilerplate on the steam ship. That, in my view, is totally unnecessary.

David: "I don't understand why a painting depicting that theme cannot serve as an illustration for the book."

"Serve" as an illustration doesn't mean to actually illustrate. Serve is a function, not an identity. Again, if some artwork is working at the level of Genus or Species - general, abstract - it may be "thematically" relevant to any story with the same general idea. So how can it actually be illustrating the one? It is more a decoration than an illustration.

A lot of romantic illustrations are interchangeable because they're poor illustrations, generic pretty girl/pretty boy stuff. And, god knows, the story might not be worth illustrating well, with nothing to recommend it as authentic/sui generis art. Why not select any painting at all to break up the gray text walls of some idle time-passing yarn. Why not use a photo of your favorite movie stars

David: "I don't go looking for the date of manufacture on the boilerplate on the steam ship. That, in my view, is totally unnecessary."

You seem to have it in your head that my criticism was that the picture didn't show the proper boiler room for a coal-fired steamer of the exact date of publication or the general time period when Conrad was living on one. But the actual criticism is that he didn't paint a boiler room of a steamer at all.

And he went with his photo of himself with a shovel instead of Conrad's actual description of the character.

I agree that perfect authenticity is not necessary. But frankly contradicting the text erases the author's work, or at best confuses it. That is hardly a service provided. This is hardly illustration.

Kev, you seem to be saying that in addition to "making clear" something about the story and making the picture "illustrious" (which I guess means well done?) that an illustration must also be specific to (rather than merely usable for) and "parallel" to the text rather than contradicting it. Is all that from Pyle? Is there any more from Pyle on this idea?

~ FV

David: "A book about hell could be illustrated by Hieronymus Bosch and a book about war could be illustrated by a Goya etching. Show me the rule that says otherwise.”

FV: “...that an illustration must also be specific to (rather than merely usable for) and "parallel" to the text rather than contradicting it. Is all that from Pyle? "

_ _ _

An image that is ‘usable for’ a given theme (such as ‘war’) functions like any stock image. It has a generally applicable meaning, in that it encapsulates the idea / concept of war, and could be used on any number of books of the same theme.

An image which attempts to stage a specific scene from a specific text becomes more and more specific to that text only, and less usable generally.

To go back to the starting point of David’s post: the only illustration from the examples which actually resembles a scene from the novel is number 6 (which illustrates the first time HH sees the girl in the garden). Therefore, if that was used on another cover people might say “hang on, this looks like the opening scene from Lolita”)

~ FV,

Yes, all Pyle; some put in my own terms.

As far as more simple aphorisms, he said it was the illustrator’s job to "illumen". Which meant to brighten, adorn, enlighten and inspire. This is of a piece with “illustrious” which meant bright, conspicuous, distinguished, and noble. Which goes beyond “well done” into something more like “grand”, “shining”, “impressive” and “important.”

There was no distinction in Pyle’s time and mind between truth, illumination and enlightenment, or between clear, beautiful, and insightful. The meanings all blend together, like wet and water.

Connected to these ideas, Pyle also thought of illustration as an ennobling and educational art. And he became so enamored of the idea of the moral purpose of his work and that of his students that he very nearly incinerated his classic haunted Flying Dutchman scene because the subject was so dismal.

I can safely say that he would have been against any illustrations of Lolita and probably its publication as well.

You said it better than I did, Laurence!. Thanks.

Anonymous / Bill-- Jumpin' Jehosophat, I like the expression "Holy Hanuman."

There's a fundamental problem when we start declaring someone's art inexcusable on moral grounds. The Taliban wants to say that the buddhas are immoral but on the other hand they believe that god has 72 little nymphette virgins waiting for them in heaven. You seem to believe the opposite, that the monumental buddhas were just fine but Lolita was immoral. Two opposite moral conclusions, both sides equally convinced they are right. How do we break the tie? Do we put it to a vote? Thats awfully dangerous, there are lots of muslims in the world. Do we say the winner is the side most willing to die (or kill) for their beliefs? I would discourage that method.

Short of a religious war, the least we can say is that the morality of art is an area to tread carefully, be tolerant, and try to understand what (if anything) is of artistic value in the other side's position. That means reading the beautiful prose of Lolita and trying to enrich our understanding the way Humbert is flawed, just as we try to understand how Captain Ahab is flawed. Certainly, if you ever got the sense that Nabokov is an advocate for Humbert's actions, that would be a reason to read skeptically. I don't get that sense.

Laurence John (and Kev Ferrara)-- I come out a little differently. It doesn't bother me that a picture "functions like any stock image. It has a generally applicable meaning." As I said earlier, in my view "the end justifies the means." If a stock image is more brilliant and profound and incisive, if it cuts to the heart of the theme of a book, if it illuminates the concept for the readers more than a hand painted picture specially commissioned for the book, then I'd say go with the stock image.

It's the illustrator's challenge to produce something better than Getty images could supply, and the illustrator is unlikely to do that merely by getting closer to "a specific scene from a specific text [which] becomes more and more specific to that text only, and less usable generally." If a character in the story wears a yellow shirt and has a funny nose, I don't think the illustrator who captures those specifics is necessarily any more "clear and illustrious" (to stay with Pyle's criteria) than a well curated image from an Etruscan pottery shard or a Saul Steinberg cartoon. It's great to capture specifics when we can, but I suspect the further we drill down on the "specifics" that make the image "less usable generally," the more we may stray from the author's larger concept.

To push back on your point about the Lolita picture that "illustrates the first time HH sees the girl in the garden," I could point to three or four pictures among my tearsheets of men who stumble across young women in a garden. There seemed to be a thing in 1950s women's magazines about handsome young men encountering pretty girls in the country bathing nekkid in a pond. Lots of blushing all around. The men always behave gallantly (although they sometimes smile at the girl's discomfort). Illustrations were commonplace of girls appearing between the bushes, innocently clothed but the guy is gobsmacked by her beauty. I'd say the Lolita picture you chose fits nicely into that genre.

"There's a fundamental problem when we start declaring someone's art inexcusable on moral grounds"

Which I wouldn't do, and didn't in this case.

If the issue has been underlined a few times by me and others, it's because of the grey area as to the degree to which it is narrating - treating of - and the degree to which it's enacting (at least to some extent on some level. There's a type of spell-casting in all art, we enter into even Ahab's madness to a degree, but it remains something of a glamour, no matter the closeness of the things to which the art brings us, there remains a distance, a seperateness; but sex is a special case, and steps out of the art and into the world very often, in a way which I don't think happens anywhere else, or rarely). I haven't read it so only vaguely know some of the cultural offshoots and not the book itself, but more than a few people who have read it, here and elsewhere, have queried this ambiguity.

I don't think this bears any relation to religious proscription. We have to believe the tenets to accept these. But ethics and morality are built on rational, undeniable foundations - spiritual as well, I agree with Kev that even for an atheist or agnostic there is a sacredness to childhood; but even without this recognition of something spiritual we all know that children are inequipped physically or mentally to become exposed to or participate in things that belong to the realm of adult maturity. This is visibly so, and deducible if it were not. That this was not always seen, respected or believed is down to the harshness of human life in the past in our own and in other cultures (even recurring today, Iraq is apparently reducing the age of censent to that of Aisha when she was violated by Mohammad), from which there has been an evolution, and that there is such a thing as the ennoblment and development of the human, which has been won over time. But people and culture can also regress.

"Jumpin' Jehosophat"

I think we've just insulted three or four religions between us.

Bill

Certainly, if you ever got the sense that Nabokov is an advocate for Humbert's actions, that would be a reason to read skeptically. I don't get that sense.

Do you think those RedTube videos of the busty teacher telling the forward student "You're a bad, bad boy" are PSAs about sexual harassment, too?

""There's a fundamental problem when we start declaring someone's art inexcusable on moral grounds ......

Two opposite moral conclusions, both sides equally convinced they are right. How do we break the tie? Do we put it to a vote?"

There are sometimes - not always, but quite often - clear right-and-wrongs, beyond culture, relativity of belief systems and so on.