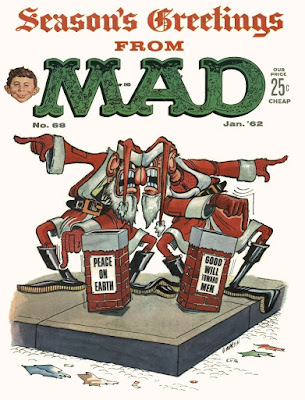

My dear friend, Nick Meglin, died this morning. For nearly 50 years Nick was the loving heart of MAD magazine and a tireless advocate for its astonishing stable of talent. The following are some of Nick's classic cover ideas for MAD.

But Nick led a much broader life, full of professional accomplishment in varied areas (he was member of the Dramatist Guild, ASCAP, the Writers Guild of America, and the National Cartoonist Society).

The best way to summarize Nick may be with this story:

Last week Nick took me to the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia. With all the knowledge and sophistication of an experienced museum curator, he escorted me from piece to piece, explaining what made Rodin great, citing details from Rodin's life and pointing out subtle features of his bronze casting technique. Then, as we were leaving he spotted Rodin's

The Burghers of Calais across the Courtyard. With all the knowledge and sophistication of an 8 week old puppy, he went over to pose pretending to return a rude hand gesture from one of the Burghers.

|

| "Meh" |

As his sweetheart (and the most patient woman in the world) Linda Maloof snapped his photo, Nick explained that wherever he encountered

The Burghers of Calais around the world, he had to get a picture of himself responding to that Burgher. The joke never got tired for him.

|

| Nick at Frank Frazetta's house, pretending to touch up a painting that needed some help |

I say that Nick was my friend, but Nick was everybody's friend. If you ever read a copy of MAD Magazine or one of Nick's many books or if you ever took one of his art classes at the School of Visual Arts or if you ever went to one of his musical plays, or even if you just believed in decency and humility and kindness, or appreciated a good insult, you were a friend of Nick's. He was a joyful and remarkable man, warm, funny and expansive. Everyone gravitated to him.

|

| Nick (far right), Sergio Aragones and Sam Viviano cracking each other up on a panel last week at the National Cartoonists Society convention. |

Nick was generous teaching me about illustrators. He seemed to know personally every illustrator of the past 60 years and he worked with many excellent artists at MAD; his memory was extraordinary and his taste was impeccable.

In recent years he began passing along to me his dusty files of tearsheets and clippings, like a relay racer passing a baton to the next generation. He knew he wouldn't have time to write all of the books and articles that remained within him, and he expected me to do my share to honor and preserve the talent we both admired.

I told him several times I wanted to sit down and tape record him for two weeks, but he always had something more pressing-- and funnier-- to do. It would have been a great service to the history of illustration and comic art. Now I'll never have that chance. Farewell, my friend.