This morning I had an illuminating chat with the legendary illustrator / cartoonist Ralph Steadman.

Fifty years ago Steadman became famous for his scandalous political drawings and his illustrations for Hunter Thompson's books, such as Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas.

|

| Henry Kissinger (detail) |

|

| Ronald Reagan (detail) |

Steadman's drawings from decades ago remain as relevant as today's headlines:

|

| Viral Menace |

|

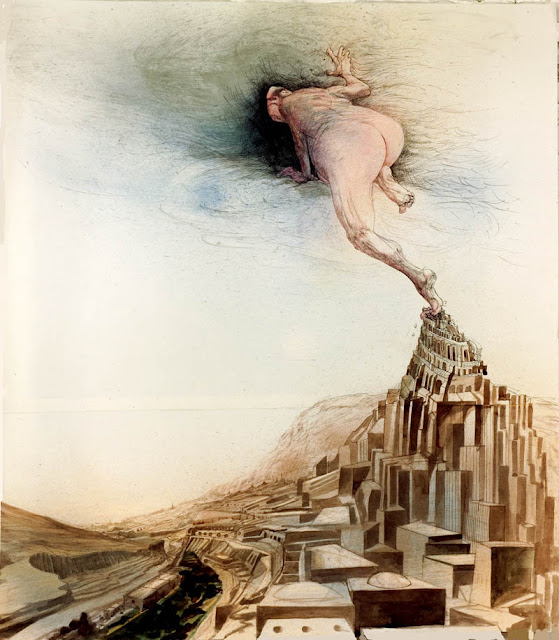

| GOD Gets the Hell Out |

Steadman's fiery indignation has not softened a bit over the intervening years. ("Trump is the worst creature who lives on this earth," he tells me.)

I spoke with Steadman about his distinctive combination of looseness and control. His drawings often incorporate accidents of nature-- splatters of ink delivered Jackson Pollock-style-- along with the technical drawing skills of a former draftsman for an engineering factory of the De Havilland Aircraft Company.

|

| A wall decoration at Steadman's recent retrospective exhibition |

He described his receptiveness to the accidental:

In a way it starts out like an abstract work of art.... Sometimes I put a piece of paper down... and I'll drop the water [that I use to clean my brushes] on in it from about 3 foot up. The smellier the water, the more interesting the patterns you get when it dries. You get textures and things that are marvelous. Decay is an interesting part of the process.Steadman also flings ink and sprays color which he blows through a tube. He says he enjoys the surprises that result from such abstract beginnings:

It surprises me as much as anybody else. That's what makes drawing interesting. I look at the accidents from the splatters and ask myself, "How did that happen?"That's what he dislikes about using computers for art:

The only thing I like about using a computer is that it can fill in a color. Otherwise computers are too beholden to rules and regulations. There aren't so many surprises. With a drawing [by hand] you can still say, "oh my god, that's interesting."After those spatters "express a creature or a person or a group.... " he develops the drawing with "the straight lines and circles" that he learned at the De Havilland Aircraft Company.

Given his receptiveness to chance and experimentation, it shouldn't be surprising that Steadman's all time favorite artist is Marcel Duchamp because of Duchamp's discovery process. He says, "Duchamp's work is so unexpected.... Everything's an experiment, and that's how it should be."

After a conversation that spanned fine art, illustration and cartooning I asked Steadman what he considered himself. "A Welshman" he replied.