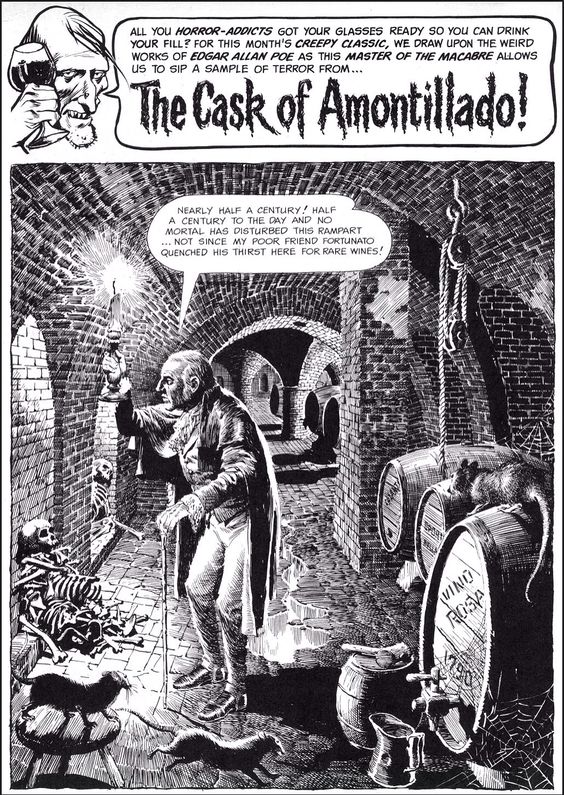

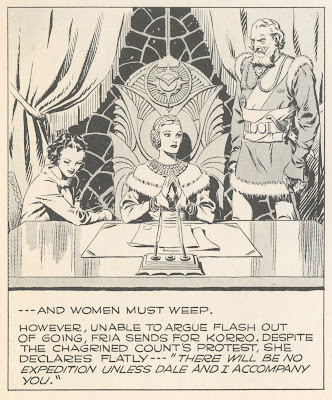

The stories in comics, pulp magazines, science fiction and fantasy were never subtle about the proper roles for men and women. Here is Flash Gordon by the great Alex Raymond:

We see a similar perspective in Prince Valiant (1972), drawn here by John Cullen Murphy:

In 1959, Hal Foster drew our hero taking a more hands on approach:

|

| Prince Valiant by Hal Foster |

The politics of these stories have been the subject of robust debate. I leave that debate to others.

What interests me is that the words are only one small part of narrative art, and the non-verbal portion-- the lines, colors and shapes-- can express a gender orientation of their own.

In the 1950s, illustrator Albert Dorne was commissioned to illustrate a story for Cosmopolitan magazine. The story involved a barn that burned down at night, a cow, and a young couple confronted by crooks. Dorne turned in this powerful illustration:

But Cosmopolitan rejected the picture. Dorne recalled the phone call he received from the art director:

"Albert, your drawing is swell but we are afraid our readers will not like it. The violent fiery red is a bit frightening, the interpretation too literal. We have found from our readership polls, etc. etc. Would you mind doing it over?"

Dorne was irritated. He recalled, "The audience in mind being primarily women, I knew I couldn't actually show fire, so I... created the illusion of fire by lighting the picture with a deep fiery glow from off stage." But that wasn't sufficient. The picture's strong, high contrast treatment, with pointed fingers, sharp angles, extreme positions and facial expressions was still viewed as too yang for a female audience.

Cosmopolitan presented Dorne with "a layout designed in a much lighter vein and quite gay in its concept." The art director explained, "This is the sort of thing our readers like."

Dorne (a powerful, cigar smoking man and former prizefighter) bitterly started over and this time turned in a much softer, pinker, friendlier picture:

To his amazement, Dorne received a flood of compliments for the revised illustration, not just from the readers of Cosmopolitan but from art directors of other women's magazines who thought that Dorne's light and charming style would be well suited for their audiences.

This was not a conspiracy between a male artist and a male art director. The patriarchy had nothing to do with these aesthetic choices. These were the colors, lines and shapes proven to induce more women to buy and read the magazine.