The 1960 Annual published by the Society of Illustrators was crackling with talent and energy.

The Annual collected illustrations by "fine" artists such as Ben Shahn, Henry Moore, Leonard Baskin and Andy Warhol, all of whom were employed as illustrators that year. Other distinguished illustrators that year included Norman Rockwell, Milton Glaser, Saul Steinberg, Coby Whitmore, Al Parker, Austin Briggs, Bob Peak, Albert Dorne, Bernie Fuchs, Noel Sickles, Robert Weaver, Joe Bowler, Robert Fawcett and Stanley Meltzoff. Legendary cartoonists Ronald Searle, Andre Francois and Tomi Ungerer also appeared in this collection.

Wrong.

Here is what the judges wrote in the 1960 annual:

"The general level of merit was low. More work should have been rejected."

"I was disappointed in the overall quality, too much that was not bad but ordinary."

"The work submitted fell, more or less, into three categories: a.) technically skillful execution of banal ideas; b.) banal execution of banal ideas; c.) some quite lively and fresh work in juveniles and paperbacks."

"The jury generally was disappointed in the overall quality of the work submitted... New trends, while interesting, do not necessarily mean good trends and their derivative 'inspirational' sources are usually rather thinly disguised."

Can you imagine reading such a withering assessment today? These judges were tough guys (yes, the judges were all guys back then) and they pulled no punches. Despite their harsh indictment, they remained pretty open minded about different forms of excellence. Here are examples of the variety of work they selected for that 1960 Annual:

|

| Bernie Fuchs |

|

| Milton Glaser |

|

| Austin Briggs |

|

| Harvey Schmidt |

|

| In 1960 young Andy Virgil was developing in the style of Coby Whitmore, Joe Bowler and Joe de Mers... |

|

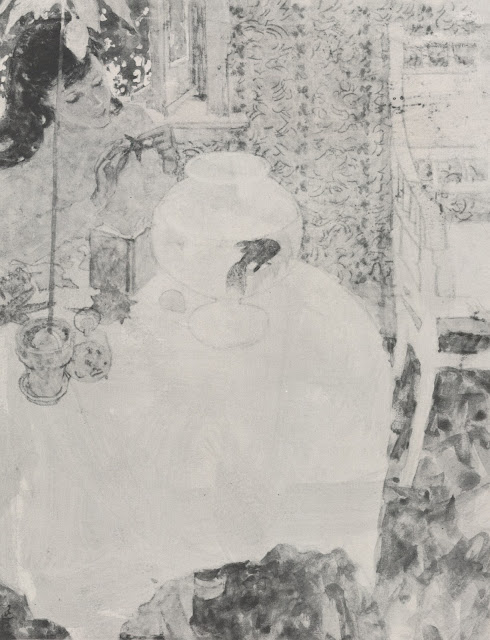

| ...but Whitmore and the others were already moving on to other creative touches |

|

| Felix Topolski |

|

| Robert Weaver |

|

| The Provensens |

|

| Jack Potter |

|

| Daniel Schwartz |

Robert Weaver's criticism was even more fundamental: "Lack of serious artists in the medium."

Hugh White complained: "too many follow-the-leader illustrators and too many still trying to do what photography can do better."

Walter Murch criticized: "the cliche."

Note that the judges didn't hesitate to sign their names to their opinions. They would've viewed it as an act of cowardice to do otherwise.

They didn't view their role as validating the feelings of artists or puffing up their work. Instead, they seemed to believe that the best way to inspire young talent and reflect honor upon their profession was to articulate the highest standards they knew, and apply those standards ruthlessly. That attitude may account, at least in part, for the quality of the artists of that era.

140 comments:

It's weird, I have trouble seeing these as illustrations. If you don't know what they're supposed to illustrate, doesn't that turn them into drawings?

If only because of that, I really like the "myths and legends" one.

"Nice girl . . ." is as fresh as the day it was born.

When all reviews can only be good reviews, the reviews become meaningless.

If it wasn't for Kennedy I would have thought those dull fat cats to be Soviet. Is there really enough space for him there? He almost seems montaged in.

The Fuchs is interesting. The left wall seems to work, but it also appears to dissolve into the floor. It doesn't match up with real space does it?

The power is quietly held by the couple on the floor. "Even lying on down here, I'm in control" Shoes and plates grab for territory while the other couple are mashed together on one chair, but it all seems very friendly. One would like to think they're all social equals and at ease with each other in the evening, perhaps with those on the chair as guests.

Marc, part of the floor between the carpet and the wall is not painted. There are also "tweaks" to the perspective: the window and the floorboard to the right are obvious.

David you wrote recently about illustration students today who don't accept criticism because they think white male racist teachers can't appreciate their work. I recall they wanted a safe space where they could criticize teachers but teachers couldn't respond. Isn't that part of the problem?

JSL

But the criticism as transcribed here is sort of... generic? I bet it could've been thought and written at any time in history a anywhere. Specially if the judges were established/former artists. I bet the scolded artist after reading them just shrugged.

As a teenager (many moons ago) I had the privilege of visiting The Society’s museum in NYC, it was fascinating and inspiring to see all the original great works. Happy to read The Society is still providing free admission to the public.

xopxe-- I agree, the "Myths and Legends" is a real beauty, So strongly designed, and utterly unlike anything else being done that year. One of my favorites.

I don't draw a material distinction between an illustration and a drawing. Is a Rembrandt drawing of two figures talking different from a Rembrandt illustration of two Biblical figures talking?

Wes-- Yes, that stirred up a lot of discussion among illustrators of the day who had previously devoted a lot of effort to painting detailed backgrounds. I don't know if you can tell from this small reproduction but among the very, very details in this illustration are wedding rings on the man's and woman's hands. After all, this was 1960.

Marc Kingsland-- Agreed, "only good reviews" may temporarily fill the role of ego reinforcement but that will be fleeting as compliments are devalued over time. These artists in 1960 weren't looking to be propped up. They spoke the truth as they saw it and were willing to stand or fall based on the quality of their work.

It's noteworthy that the illustrators in this volume were keenly aware that television and photography were starting to gobble up the advertising revenues that once funded illustration. It was a threat to their entire way of life. Yet they knew that inflating their own grades was no way to deal with the problem.

Marc Kingsland-- That Robert Weaver Kennedy illustration was of an earlier, pre-presidential phase of his career. It was the most traditional illustration in a series-- the other pictures were broken up and avant garde in Weaver's experimental style, but I liked this one best. There was a lot of experimentation going on that year.

JSL-- Complexities abound, and there are arguments to be made on both sides, but I'm sadly aware of illustration students/young illustrators who seem to believe the primary purpose of education is validation and praise, and who react to criticism or low grades by lodging grievances about the patriarchy, racism, capitalism and faculty who need to be more encouraging and warm hearted. Several of the artists in the 1960 Annual took a real beating pursuing their innovations but persevered and ended up the better for it.

Marc: "The Fuchs is interesting. The left wall seems to work, but it also appears to dissolve into the floor."

There is no left wall. Here's the complete double page layout:

https://illustrationage.com/2017/12/05/turn-back-the-pages-introduction/#jp-carousel-112812

"There is no left wall." Clearly it's supposed to be read as one though. The hanging picture, the side display table, of the sort always pushed up to the wall. Yet if it is against the wall then there's no space for the back of the single chair. However this is all part of the magician's craft.

The real question is, to me at least, is the white space to the left part of the art? Is that part (not displayed here.)which Fuchs knew would be used for text, part of the composition? I think it most likely is.

The gimmicks that Dorne rightly decries are pretending to be ‘expressionism’. But there is no thought or feeling behind them related to what is depicted. It’s just jazz jive techniques filtering the reference; slop the area, jiggle the line, scribble the texture, swipe and scrub the value, trace with a blunt pencil and don’t lift it up, etc.

So Fuchs puts his colorful lipsticks over the tracing of a badly distorted photo with no idea behind it except to make a warped quilt. Schwartz roughs in a parking lot full of cars – previously flash-frozen by photography - while ostensibly depicting a ferocious automobile race. Weaver fakes his drawing so poorly that it ends up being a munchkin-ization of Kennedy and his broken-legged fellows; the interior completely unimagined and false. Topolski fakes his tail off trying to "loosely" pretend he knows what he is drawing about. The Ingegno bets all on a listlessly inarticulate silhouette. Then frames it with the scribbled kid cloud. Schmidt also garbles the single key silhouette in his picture, and slops the rest in, also pretending such is ‘loose.’ Potter attempts a Red Rose Girl style image, but bluffs the drawing instead of concentrating on it.

It was truly a dire time for illustration. When so much narrative work was reduced to fashion art; slopped in graphic designs pretending to be poems.

Marc: "Yet if it is against the wall then there's no space for the back of the single chair."

I agree, it looks wrong. If the blue chair is correctly placed - the back of it almost touching the invisible wall - then the foreground table would be about 2.5ft away from the same wall.

Marc: "However this is all part of the magician's craft."

If something in a picture looks off and breaks the illusion then it's just the opposite of stage craft. A question like "what's going on with that table ?" is the last thing a painter wants to hear.

Marc Kingsland and Laurence John-- I hope your observations about the left plane of the Fuchs picture will help open the eyes of those who mistakenly think Fuchs simply "traced a photo." Those elements would not be out of alignment if Fuchs was tracing a photograph (unless of course the photo slipped in the balopticon and Fuchs failed to notice).

However, I disagree with you that the left side of the Fuchs picture "looks wrong." I do agree it looks inaccurate as a photograph, but that was not Fuchs' primary concern.

Cezanne is widely celebrated as the father of modern art for inventions such as "breaking the plane," disconnecting lines and distorting perspectival space to build a composition with structural tension and movement. If you look at the horizontal plane of the table top in Cezanne's Basket of Apples you can see it doesn't align because Cezanne sacrificed the laws of classical perspective for artistic effect.

It seems to me that, for the same reasons, the items on the left side of the Fuchs painting are arranged to maximize the effect of the dynamic swoop. The distortion of the lampshade could just be a wide angle camera lens, but the placement of the chair and the table in the foreground and even the tilt of the left wall in the corner where the wall meets the back wall all seem to contribute to the effect Fuchs wanted.

If the chair was pushed back to the left wall and the wall was perpendicular to the ground, it might look more photographically accurate but I think that accuracy would have a deadening effect on the picture. By moving the chair forward Fuchs silhouettes the shapes of that lamp (creating a bridge to the white space) and creates some excellent negative shapes behind the lamp.

Kev, I agree with everything you said about the illustrations.

The following year Potter won and award for excellence with a much better illustration and Briggs also made better contributions.

On the Fuchs...

The missing wall and the missing hardwood floor in front of it have no physical or narrative meaning. Their eradication has left a graphic space shaped to accommodate the text and to direct the eye dynamically into the picture.

In erasing the area to the left of the slate blue chair, the back of the bookcase where it would have met the hardwood floor has also been erased. Which confuses the location of the wall with respect to the back of the chair (due to insufficient suggestive information.)

Visually calculating what's been erased, it looks to me that there's about three feet of hardwood floor gone missing, certainly enough to accommodate a chair.

Given that the angle and type of the distortion of all the elements on the left side and foreground match, it is safe to assume that the chair is properly traced from the distorted photo reference. As is everything else.

Further proof, if needed: That the back of the bookcase that would have been showing awkwardly behind the slate blue chair was excised - also awkwardly (leaving the 'bad narrative question' about the pictorial space) it must be assumed that the blocking of the elements was not designed by hand, but is rather the result of accurate photographic reference creating awkward shapes. Which Fuchs then edited out.

It's obvious to me that the intention of the left side of the picture is to end the picture interestingly and merge it into the text that goes to its left. Instead of giving an arbitrary borderline, the illustration is cut along non-obvious lines from the drawing (for example cutting on the rug and not o the floor/wall edge). So the text wraps around the cake figures, and so on.

What is interesting is that the drawing perspective is broken on purpose, but there is also a perspective effect applied to the text. This second effect is also broken due to the limitations of the typesetting methods (and becoming very hard to read if done "correctly" anyway). It's not true perspective, the text is just left aligned to the inclined border. On the other hand, the title is actually skewed. So the text portion has internal inconsistencies due to practical reasons, that mirror the inconsitencies in the drawing portion.

David, I do see a Rembrandt of two biblical figures talking differently than one of two randos talking. In the latter, what the drawing can change and be affected by is what I know about the world. In the former, is that plus a piece of culture. Say, Alice is Victoriana purely because of Tenniel, Russian folklore is epic because of Bilibin, and hell is beautiful because of Doré.

Kev Ferrara-- I'm glad you've taken to heart my point that tough criticism is important, but I should've added that toughness alone is not sufficient.

You strain so hard to disregard the obvious qualities in these pictures that even your considerable eloquence is overtaxed. It's not clear to me why you'd say that Fuchs' distorted photo reference is "badly" distorted, nor why it "had no idea behind it," nor why you dismiss that splendid carpet as a "warped quilt." I'd say barely one in a hundred pictures by Pyle or Dunn can match Fuchs' delicate interlacing of figures here or their subtlety of expression-- many of Pyle's and Dunn's figures seem physically and psychologically wooden by comparison. Fuchs uses a different palette from a different generation, but I suspect Pyle and Dunn would be impressed by the way Fuchs highlights that crucial white sock, or implies the richness of the pattern of that wallpaper.

The Schmidt and the Inegno were born in an era when abstract expressionism was king. If you see no redeeming virtues in abstract expressionism it's unlikely that you'd forgive Schmidt or Inegno, but I cheer their efforts to combine some of the visual power of abstract expressionism with narrative content, and I included them here as examples of the great variety that was accepted in the 1960 Annual with an open mind. Austin Briggs could paint realistically but became a charter member of the Museum of Modern Art.

The Potter (and some other pictures) suffer from being reproduced in black and white, but I included Potter because I think he is one of the unsung heroes from that era; he worked in Bob Peak's Schiele style before Bob Peak did, but withdrew from illustration at a young age without waiting around to collect honors. I find the Schwartz painting to be well designed (as is all his work) and if you don't think his tilted ground does enough to convey speed, I'd be interested in examples of who you think does it better. Pyle and Dunn never had to paint anything much faster than a trundling ox cart. I recall you once disapproved of Al Parker's blurred lines for conveying a speeding race car. So I sincerely ask: steer me to those you think do it right.

I can never guess which issues or images are going to trigger conversation around here, which is much of the fun. As the white border on the left side of the Fuchs painting seems to be a point of some controversy, here is a little history which I learned from interviews years ago, and which some of you may find interesting:

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, famed art directors Otto Storch and Richard Gangel challenged their top illustrators to come up with fresh ways to blend images and text. The illustrated magazines were losing their audience (and their advertisers) to television, and management wanted to invest their substantial resources in fighting back with more creative use of the unique strengths of magazines. They began publishing in larger format, giving illustrators wide discretion to fill full color double page spreads-- far more space than illustrators ever had before.

The magazines wanted to hook the attention of readers with bold, imaginative images but also to convince readers to stick around long enough to read the accompanying stories. (Subscribers were already getting lazy about reading text, as they discovered that passively listening to TV and radio required less effort). Storch asked Fuchs, Whitmore and a few other greats to look for creative ways to marry the words to images, emphasizing use of the new capabilities of headline typography. The result in the early 60s was a series of illustrations like the Whitmore (Nice Girl From Boston) and the Fuchs illustrations in this post. Fuchs also received a lot of praise for a double page spread (https://farm4.static.flickr.com/3445/3864175547_f6b677e58a_o.jpg) which Storch showed to other illustrators as an example of "the new look." A third example is his double page spread for the Graham Greene story, "The Invisible Japanese Gentlemen" which is buried in the middle of this earlier post of mine: https://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2020/06/the-energy-of-1960s-part-3.html

The point is, while we deliberate about the shape of, and aesthetic reasons behind, the white space in these illustrations, there was also a purely economic reason, dictated by the bosses of the big magazines trying to hang onto their jobs. Ultimately, this strategy was a failure but it helps explain an unusual trend in the early 60s.

David, that story makes a lot of sense. Interestingly, I saw that text/image merged style's rebirth when cheap Desktop Publishing became a thing in the early-mid '90s. I did quite a bit of it on PageMaker 4.0 because it was really easy to do (just flow text and tweak the figure borders), and it looked expensive because before it was usually only seen on professionally designed materials. Before desktop computers, doing that artisanally meant using a photocopier, scissors to cut lines, and lots of glue (hello underground fanzines).

Then Word implemented that functionality, in a limited and ugly fashion, and it lost its aura.

You strain so hard to disregard the obvious qualities in these pictures that even your considerable eloquence is overtaxed.

I don't strain to be honest. It would be more of a strain to force myself to appreciate trivialities like technical execution, pretty colors, fake looseness or graphic design when a picture doesn't make sense aesthetically.

It's not clear to me why you'd say that Fuchs' distorted photo reference is "badly" distorted

It is severely distorted in a way that only a camera distorts.

Thus, when looking at the Fuchs picture - which is ostensibly a quick sketchy rendering of an interior - what enters into the mind unbidden is the point that it is obviously not an image of an interior at all. But a picture made of a photograph of an interior. The evidence (thus idea) of a photo-shoot is woven into the very fabric of the picture.

So the whole pose of it being some spontaneous rendering of a spontaneous moment instantly self-falsifies. It's a kind of shallow trick as short-lived as Tromp L'Oeil's pretense of presenting real objects.

Aside from the error of "caught being tricky" I really find it amazing that more people do not react negatively to the stupidity of photographic outlines as compositional scaffolding. Photographs are just utterly vacuous mentally.

Great art is full of aesthetic and imaginative decisions. Photo-dependent art is full of decisions about the photos.

why you dismiss that splendid carpet as a "warped quilt."

I agree the carpet is rendered splendidly. However, I meant the whole picture is a warped quilt.

What I have written above should not be taken as a blanket criticism of all Fuchs' work. This particular piece just seems to stick in my craw more than most.

The point is, while we deliberate about the shape of, and aesthetic reasons behind, the white space in these illustrations, there was also a purely economic reason, dictated by the bosses of the big magazines trying to hang onto their jobs.

Not «also», but «primarily».

I’d hazard that (different) photographic reference was used for the figures, who look as pasted in as the flying saucer in the previously posted Wyeth. The scene might easily/economcially have been entirely invented on the spot to fit the technical needs of the AD. Start by establishing a narrative connection to text, mock up a basic composition, utilize reference, add interesting shapes, motifs and textures (while having a finger on the pulse of contemporary culture), refine and submit and done, done, on to the next one.

David: "It seems to me that, for the same reasons, the items on the left side of the Fuchs painting are arranged to maximize the effect of the dynamic swoop."

I agree that the diagonal of the left side of the table works with the perspective and goes with the leading of viewer's eyes into the main focal point.

Kev: "Given that the angle and type of the distortion of all the elements on the left side and foreground match, it is safe to assume that the chair is properly traced from the distorted photo reference. As is everything else."

I don't have a problem with the invisible wall or the missing lower bookcase. Just that the foreground table that looks like it should be against the same invisible wall (due to the hard diagonal of its left side) clearly isn't.

Anon: "I’d hazard that (different) photographic reference was used for the figures, who look as pasted in as the flying saucer in the previously posted Wyeth. "

It's probable that Fuchs took multiple shots of the same set up and picked the best poses, but it's also possible that the entire scene is one shot. I disagree that the figures look 'pasted in'. The entire illustration is playing with varying degrees of naturalism vs graphic flattening... edges are too hard, values are deliberately over or under emphasised, colours are over or under saturated, rendering is deliberately rough and simplified in a 'poster' like way in places ... all of which contributes to the feeling that the marks are 'sitting on the surface' more than receding correctly in 3-D space as they would in a more conventional painting.

What we're looking at is a photographic image that has been rendered as painterly graphic mark making, with deliberately non-naturalistic effects. Hence the slightly off kilter feeling of real space vs flattened / cut and paste / collage.

David, incidentally do you know if this painting is gouache or acrylic ?

Kev: " I really find it amazing that more people do not react negatively to the stupidity of photographic outlines as compositional scaffolding"

I enjoy a lot of the images that Fuchs and his peers produced, and I can even understand why the camera became such a much used tool during this period, but I always notice when an image has an obvious photo-ref base, and it alters the way I perceive (and judge) the final image.

Aside from that, these days I'm much more interested in paintings and drawings which move away from an attempt at 'realism' altogether, so obvious photo-ref based modern works usually fail to engage me at all (with the exception of someone like Nicolas Uribe who is such a good painter that his work is worth looking at for the painterly qualities alone, despite the photo-ref use).

The entire illustration is playing with varying degrees of naturalism vs graphic flattening... edges are too hard, values are deliberately over or under emphasised, colours are over or under saturated, rendering is deliberately rough and simplified in a 'poster' like way in places ... all of which contributes to the feeling that the marks are 'sitting on the surface' more than receding correctly in 3-D space as they would in a more conventional painting.</b

Well put. By «pasted in», I don’t mean that it is shoddily done. In the Wyeth, an alienating effect is produced - here, I have the impression of an artist being acutely aware of his cultural surroundings. It is a work expertly & very much of its time.

I suspected art directors were responsible for sending illustration in the graphic direction. Thanks to David for explaining the adaption of graphic influences to accommodate text at the request of art directors.

Potter was a very influential teacher in LA and New York in the 60s and 70s and the schools were teaching Manet’s flat shapes over form in high school by the late 60s. The drawback was that students didn’t learn how to draw form. The era celebrated photography and its graphic nature as “interesting” and graphics had already taken over fine arts. Artists like Neil Welliver and Fairfield Porter who relied heavily on flat shapes were among the first to bring back realistic painting as photo realism was making its debut.

The younger artists like Potter were about 30 years old around 1960 and I learned to draw with Potter using shape as he taught. Not drawing form left me in a bad place by the age of thirty and I had to relearn how to draw form because tracing from photos, which everyone was doing by the mid seventies, held no interest for me.

The images Kev mentioned have obvious flaws including the distorted lampshade in the Fuchs. Some of the images from the 1960 and 61 annuals were attempting to emulate Willem De Kooning’s “gesture” paintings as well as graphic influences from Degas and other Impressionists. The excesses of expressionism were eventually left behind. I disagree that the era was a total disaster as Fuchs did develop the style most have come to identify him through such influences, but for students of the 60s and 70s, they had a steep hill to climb to try and find what the graphic influence was about, no less to discover the form that was lost.

My sincere apologies - again!

I really have no idea why this happens, but it only happens when writing on my iphone. It’s happened before, so I’ve been very careful with my html. But obviously, I’ll have to only use my PC for this site.

Also, as I’m publishing anonymously, I can’t edit or delete my post. Though, if Apatoff can, I suggest he try deleting my threadbreaking post.

SEAN,

Thank you for that interesting story about STUDYING WITH POTTER. Anything further you can add about THE TEACHING of 'FLAT SHAPES' would be appreciated. What was the RATIONALE? And how was this taught in reference to LIFE DRAWING?

Aside from that, these days I'm much more interested in paintings and drawings which move away from an attempt at 'realism' altogether, so obvious photo-ref based modern works usually fail to engage me at all (with the exception of someone like Nicolas Uribe who is such a good painter that his work is worth looking at for the painterly qualities alone, despite the photo-ref use).

LAURENCE,

Agree. URIBE and (for example) FLUHARTY are two examples of great modern artists working in real media who THOROUGHLY UNDERSTAND STRUCTURAL FORM. They have internalized it to such a degree that they can revivify what has been frozen (and reinflate what has been flattened) by photographic capture.

I am interested to hear WHO you are looking at.

Kev: "They have internalized it to such a degree that they can revivify what has been frozen (and reinflate what has been flattened) by photographic capture."

I like that idea of imaginatively 're-inflating' information that has been flattened. I agree that Fluharty is an exemplar of that very thing, and it also demarcates the difference between a 'traced' image and one that has been rebuilt from the ground up. I don't see Uribe as being an inflator though in quite the same way. To me, he's playing in the same semi-flattened / graphic realism space as Fuchs. I actually think he's maybe the best modern incarnation of the style of realism + deliberate flattening that goes roughly: Whistler, Degas, Lautrec, Klimt, (skipping too many early-mid century illustrators to name), Fuchs, David Levine, Barron Storey, Sienkiewicz...

He doesn't trace from photos, and he distorts more than Fuchs, but his concerns are the same as listed above: overly hard edges, saturation, value skewing, weird colouration. If you look at his recent Instagram posts you'll see he's currently geeking out on Vuillard, which says a lot about his interest in flattened space and non-naturalistic colours.

Regarding other artists I'm interested in; I like so many and for so many different reasons that it would be too long a discussion to get into all the reasons why and caveats. I prefer to only mention other artists that are relevant to the discussion, which is set by David and this audience, or that I think other readers might like (which is why I mentioned Uribe, as he seems an obvious fit for this blog).

Love these conversations, opens my mind and introduces me to new artists.

Kev,

Potter was a man with strong likes and dislikes, of purposeful gate and given to black and white concepts. He had a commanding theatrical voice and dramatic teaching style, pacing the room offering ongoing thoughts while the students drew. Each class was based on a premise, large vs: small, long vs: short, soft vs: hard, sometimes just a silhouette with a touch of light, etc. After several tries he would choose a student’s piece and walk it around the room saying emphatically, this is what I want! Jack was much loved but fewer ever really shared a word with him. There was something of a cult following regarding his charisma as almost every fashion illustrator in NYC had been directly influenced by him.

I never understood why one would choose one premise over another, or what exactly was going on and I didn’t know anyone else who did either. The classes were somewhat cryptic. It was just easy for me to do what was asked and after a time I got down as I realized it wasn’t me who was thinking and I quit drawing for about a year. A second teacher Sam Martine also taught drawing based on shape but in an approachable manner and he explained the punishment and reward methodology many teachers used and also the rationale that we recognize things first by their shape. He explained that the dark outline was the basic formula in commercial art, holding the shape together and defining one shape from another. He talked about how the photograph eliminated the drawing and other related subjects, such as breaking the formula and how to draw from photo reference at a distance as if it were life. But the approach being very simple was meant as a beginning point and left very much unanswered.

Potter was a fashion illustrator so that was likely his rationale. What Sam Martine was talking about went back to poster art and also stained glass. But it was confusing at the time as these two teachers who made up the commercial art drawing department at SVA taught nothing about form. I guess it also was assumed that one understood that drawing was part of telling a visual story, but for students who were lost in the weeds, such an assumption was a vital omission.

I remember reading a book called The Disintegration of Form in Art published in 1968.

It was a subject of concern at the time.

https://www.amazon.com/Disintegration-Form-Arts-Erich-Kahler/dp/B002C1C5DK

Kev, in your last paragraph (box form) are you talking about this kind of thing ?

(I can't find a Wyeth example).

https://www.geek-art.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/comic-book-illustrator-bernie-wrightson-dies-thumb640.jpg

PS:

One thing both Jack Potter and Sam Martine introduced in their figure drawing classes was line variation as weight, which differed from the simpler standard understanding of line variation corresponding to what is in light or shadow.

The heavy rolling line variations in Carl Erickson’s 1930s and 40s illustrations expressed the actual heavy weight of wool coats and jackets of his era. Potter taught to accentuate the pinch at the waist with heavy line too, which was another use, where Martine taught a pair of slacks would have heavier lines as they fell closer to the ground. In the same way a light cotton blouse, (like one in sunlight) would have thinner lines. This was very complicated stuff to be digesting before one understood line variation as light and shadow. Line variation adds interest, but it has to correspond to something understandable or it’s just complexity as its own end which isn’t desirable. So the idea of keeping a shape simple was complicated by line variations expressing multiple things.

It was refreshing to take a look at NC Wyeth again after reading Kev’s last post, where Wyeth organized many smaller shapes into a few larger tonal shapes. That’s another function of light and dark and the organization of shapes that one might learn presumably in another class. In truth, learning line variations and edges was never really addressed as their own subject. So while students in Potter’s class were drawing straights and curves with robotic emphasis mimicking the passion of their teacher’s voice, Potter’s own use of line as a searching and sometimes feathered edge expressing a sense of tenderness, time and affinity was difficult to weld with the passionate intensity of his class.

The result was something like a receiver in football trying to run before they catch a ball, or in text, not remembering that oral words can have several different spellings for different meanings. Unlike in such areas, in drawing it takes a bit of training to spot the inarticulate fumbling of shapes that are either too similar or too confused to clearly express something. That’s really what happened with the post. Kev noticed an indifference between shapes as various blunders, but then the exchange revealed many new pieces of information.

To his credit, when Bernie Fuchs abandoned the type of painting he was doing in this post, he moved into the purely graphic area timidly, adding slowly to his vocabulary of flatness gradually increasing his intensity of tones, colors, edges and thoughtfulness.

> where Wyeth organized many smaller shapes into a few larger tonal shapes

Are there any serious artists working with value who don't organize/structure their values (compressing values into "local values", simplifying shapes for readability / "good shapes", working towards a ~70:30/~30:70 shadow to light relationship, and editing out acute angles)?

It would seem to me that's the foremost distinguishing feature between an beginner and an intermediate painter.

Sean,

Thank you so much for sharing that.

If I may say, your Potter anecdotes fall in line – almost too conveniently-for-comfort - with this whole developed picture of visual art education degrading through the 20th century.

The long reductive slide from imaginative naturalism and Imagism to imaginative graphics and cartooning. Then to the linear, flat and pseudo-abstracted, then to traced or primitive, and finally to binary punk juxtapositions - mere oppositions - and then to nothing at all with the destruction of all belief in unity and meaning.

Afterwards, more recently, we get the mostly sad attempt to march back out of that aesthetic wasteland; where otherwise talented artists – alienated from the traditions or legacies in which they should have been mentored – made due with learning from mostly fake classicists in personality cults and photo-realist obsessives. With the shining exception of artists like Uribe, Leffel, Fluharty, and Dan Adel. The latter of whom once stated his purpose as “The Undoing of the Undoing.” Which I think goes for anybody producing quality these days in defiance of Le Deluge.

Your point about line weights is also interesting. I’m sure you know those kinds of conventions were taught to comic artists. Essentially teaching the craft as a suite of line-based glyphs to employ tactically as certain situations arise. Which is not that far away from Manga training.

The Line Projection effect you are talking might be the apotheosis of reductive convention-based training. Where, instead of inflating form by pushing out or receding planes, the line itself – merely a surfaced symbol of an edge - becomes the basic material reality. The reduction of plastic form to plastic line.

This kind of weirding of experience via symbolic involution became even more evident when comic artists more recently began putting edge lighting on thick lines that were only functioning as lines. This is essentially typographic thinking; akin to 3-D block letters.

ADDENDA:

Forgot to thank you for the book recommendation, Sean. Just ordered it from ebay. Thanks.

~ Kev

Richard,

What you're saying is true and pretty basic but Wyeth does it so well. It's not the only way to organize a picture and not everyone thinks in terms of formulas such as 30:70 or 70:30 shadow to light relationships or editing out acute angles. There are just a ton of ways to make pictures and it takes a long time to understand a subject like line weight for example. It sounds easy enough when someone explains it but to internalize the different uses for line weight until one sees and draws by its terms can take years to develop. I was addressing Kev’s question as to how Potter approached teaching the figure in life drawing as a shape and after seeing the Wyeth it was an extension of what Jack Potter and Sam Martine were teaching in their graphic approach to figure drawing, which was simplification, but they were teaching graphic form in the figure and not volume which is what Kev was talking about.

So on the surface of it the turn to graphics in illustration was emptier because it is, but it wasn't so simple that by magic people could just sit down and understand all there was to it. The errors pointed out confirm that while art directors may have pushed it, not everyone knew how to work it as effectively as say Fuchs did later in his career. It demanded that the few elements used in the graphic image were different and distinct enough to say something and there was no place to hide if they weren’t. That wasn’t happening in some of the images critiqued, Ingegno, Schmidt, Topolski and Schwartz. In the Briggs the two feet joining the two men aren’t really on the floor and something happened to the hands in the Potter.

As a businessman warns a beginner, you’re going to make mistakes, so try to make little ones. I think Fuchs understood there were ways to mess up the spontaneous look and what he was doing in 1961 was very thin, light colors, little contrast. It was a good bit subdued from the wild scratching and clawing that made up early attempts at excitement.

Kev, I hope it's a good read for you.

xopxe wrote: "Before desktop computers, doing that artisanally meant using a photocopier, scissors to cut lines, and lots of glue. Then Word implemented that functionality, in a limited and ugly fashion, and it lost its aura."

If you read late 19th century books and magazines about illustration, you find a sense of increasing alarm that wood engravers were being replaced by photo engraving. Dedicated craftsmen who had converted the art of Gustave Dore, Howard Pyle and Winslow Homer into engravings for reproduction had been viewed as part of the team for a century. They often signed the final result along with the original artist. What would become of these cherished, highly skilled talents and their families? It seemed the art world was coming to an end.

Kev Ferrara wrote: "I don't strain to be honest."

You are very fortunate. Many people find that honesty requires self-examination, reflection, and reconsideration of principles.

Laurence John-- I think Fuchs rarely used acrylic, as it wasn't yet a very helpful medium. He mostly trained on casein and gouache, which is how he painted this illustration. He attempted watercolor early in his career but found he was a horrible failure with transparent mediums. Later of course he converted to oils.

Kev, thanks for the clarification.

Assuming it's the same artist, what do you think of Daniel Adel's recent work - the 'Hyperabstraction' series ?

"I think Fuchs rarely used acrylic, as it wasn't yet a very helpful medium. He mostly trained on casein and gouache, which is how he painted this illustration." (David)

A long time ago I came across someone who wrote, and I quote from memory: "Degas would have loved acrylics" and it immediately occurred to me that this fast drying medium could be used like a liquid pastel, applied in combinations of scumbles and broken painting layer on top of layer to both draw form and build hue, luminosity and texture. I've used the method for twenty years now and I'm surprised to hear that Fuchs never took to it. I believe the same can be said of Mark English whose surfaces have a similar facture to the later Fuchs.

David, yes. For example as anyone who loves XIX-century science and technology I *love* the signature (Louis) Poyet. It was all over the place, but somehow he's barely known and doesn't even have a wiki entry in english, only french and russian. (tough scientific illustration as a whole gave a hard fight: Scientific American journal switched to photo illustration only in the '90s)

And yes, these transitional times are a curious thing. When a new technology or medium appears, one of the means to establish itself is to show it can do something that is "classy but expensive" cheaply and efficiently. For example, the first electronic synthesizers were advertised as church pipe organ replacements. And it can be argued that synthesizers were finally accepted as musical instruments after Wendy Carlos' "Switched-on Bach" album. It was only sometime after that their true expressive power was found: manipulation of the timbre at a level completely out of bounds for previous musical thinking. So new technologies pass through a phase of "we hate it because it is used to cheapen beauty" to another of "we hate it because it's used to do this thing we don't understand/care for". This happened to synthesizers, photography, CGI, moveable types and Offset printing.

Sean Farrell wrote: "One thing both Jack Potter and Sam Martine introduced in their figure drawing classes was line variation as weight"

Thanks for your very helpful and informative discussion of this. (I like your description of Erickson's "rolling line.") I've always had a preference for drawing, and especially enjoyed that era when drawing re-asserted itself as a medium that could own a double page spread. Noel Sickles, Austin Briggs, Erickson, Bouche and others showed the richness of a sensitive, carbon based line to convey not just weight but volume, movement and a host of other properties. This was a very different world than the ink linework of Gibson, Lowell, Flagg and all those Life Magazine pen-and-ink guys. I attribute the flowering of carbon based illustration in part to the increased ability of printing technology to capture more delicate lines. I spoke with the son of Austin Briggs who relate that after years of full color painting in oil and gouache, his father considered it a personal triumph when he first persuaded the art director of Cosmopolitan to accept a simple pencil drawing for a full page illustration. That seemed to open the door for a lot of other illustrators and led, among other things, to Briggs' award winning series of TV Guide ads.

Another great draftsman, Robert Fawcett, didn't draw with the same nuance as some of the aforementioned, but he too showed how linework could dominate. And Al Parker too.

I haven't seen enough of Potter's work to understand everything he bought to the table, but like the other artists he seemed to wed a highly selective line with a strong sense of design, and the result sang to me in a way that cluttered paintings often did not. I think Peak borrowed Potter's style for some of his own fashion drawings.

I spoke with a student of Potter's just last month who said that while Potter could've had a long and successful career as an illustrator, he abandoned that path relatively early in his career because he preferred teaching.

chris bennett-- a good point. I think Fuchs first learned to control a brush when painting car illustrations in Detroit, and acrylic, because of its fast drying and limited blending qualities, was not the medium of choice. I know he often used acrylic to paint a foundation or background colors for preliminary studies, but I think he usually went over them with gouache or crayon of some other medium for the fine tuning part.

Fuchs' later styles were more accepting of scumbling and broken surfaces, but he was soon into oil glazes because he liked that "illuminated from behind" affect and never really turned back.

interesting that you mention Degas; Fuchs said on more than one occasion that Degas was his favorite artist.

xopxe "it can do something that is 'classy but expensive' cheaply and efficiently"

Does the new technology produce more than the surface appearance of class for viewers who don't appreciate what goes on below the surface?

You are very fortunate. Many people find that honesty requires self-examination, reflection, and reconsideration of principles.

David,

Do you really 'strain' to self-examine, reflect, and reconsider your principles?

"Many people" - in the interests of sanity and the Way of Logos - make deep consideration an integral part of their adult lives. Such that intellectual-ethical self-maintenance operations become reflexive rather than a bother. Like brushing and flossing.

Unmentioned, the attempt to be honest also requires a tough stance on one's knowledge quality. Skepticism of "authoritative" sources. Even a skepticism of one's own faculties, biases, nostalgia, sympathies, research abilities, and due diligence.

More cutting still, one might need to adopt even a skepticism of the public persona one routinely projects; for fear that one might say things habitually for political reasons in order to be seen in a good light by hyperreactive tribal affiliates or to avoid the scorn of the more fragile flowers bearing earwitness.

There are so many pitfalls; so many ways to derange the honesty of a communion.

Kev, thanks for the clarification.

Assuming it's the same artist, what do you think of Daniel Adel's recent work - the 'Hyperabstraction' series ?

Adel is a very crafty artist, in all senses of that word.

The 'Hyperabstraction' paint-roller stuff is him showing up Jackson Pollock. By simultaneously creating an aesthetic reality that feels representational and doing 'action painting.' Meanwhile having a concision of design that Pollock could never imagine.

I don't much like it. For me, it falls under the heading of 'tricky.' But I appreciate it both technically and philosophically. Luckily it doesn't seem like he's abandoned his other subjects in the meantime. At least not yet.

Kev and David,

My first statement that having not learned much about form left me in a bad place for a number of years means I agree with Kev entirely that something got lost along the way and I discovered why I think so many artists having tried to emulate the expressive line of Carl Erickson, Bouche and a few others failed so miserably. I agree that design flows from anatomy and form in space and Bridgman is a good reference to learn about these.

The many who tried and failed at capturing the elegance of these artists, did try to turn line into a type of god without understanding form anatomy and space. Line does recede or come forward with what each is depicting and where it is in space. With this understanding large chunky lines could come forward and recede as desired because the artists understood enough about form to put them in space. They understood that a thick black line acting as an edge shadow, a core shadow, a shadow in a seem or a shadow revealing form under a dress, came and went according to what and where that something was in space.

The three dimensional space is there and all is where it’s supposed to be, but without a full build out of form, freeing the eye to move through the shapes guided by edges and accents. Accents identified themselves in space accordingly and turned shapes inward and outward connecting to the next shape. They were working from models, but also understood anatomy. It would have been impossible to have done these otherwise.

The undulating lines were designed to move as edges and with the form as well. The best of these artists weren’t without form at all and divided their drawings as foreground, middle ground and a hint of background, just as the figures had an eye level, a middle below it and a ground to stand on. The lines themselves were drawn far more carefully and deliberately than they appear just as Sargent painted brushstrokes which were more deliberately painted than they appeared.

Carl Erickson:

https://i.pinimg.com/474x/72/c0/e8/72c0e81fe2a99f77d5c40e3a949a883b--s-fashion-fashion-prints.jpg

https://www.oakauctions.com/ItemImages/000004/4800b_lg.jpeg

https://hprints.com/s_img/s_md/45/45739-ceil-chapman-1949-eric-carl-erickson-1b46656e5bfb-hprints-com.jpg

Potter:

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/e6/60/eb/e660ebc99b072124c3915dc3aba8a2df.jpg

Daviud: Does the new technology produce more than the surface appearance of class for viewers who don't appreciate what goes on below the surface?

At the beginning, the point is to reproduce the surface, that's the point. First, it is unclear what the new technology is good for, yet. Then, you go for what seems to be appreciated and a status symbol. So though it can produce any timbre existing or imaginable, you reproduce pipe organs. Though it can print any text, in any numbers, you print bibles. The first commercial application for CGI was "flying logos".

Furthermore, the vast majority of viewers only recognize effects as signifiers of class without knowing what's "bellow the surface", only that it seems to appear on more expensive work. How does a typesetting system work? What's inside a Stradivary? How do you produce that blue pigment? The majority of even art enjoyers *does not care*.

Sean,

On the 'fashion illustrator' topic...

How do you see those artists you linked and the qualities you find in them in relation to John LaGatta work?

LaGatta 1

LaGatta 2

LaGatta 3

LaGatta 4

Kev,

I have to say that your comments and the addition of the Wyeth pirates with the Bridgman blocked heads, and the Wrightson spoke a million words to an important theme of yours. There are so many ways to build space using differing shapes and forms, the blocked head, the swords, the breaching of the wooden fortifications, the tones and color, the hulk of the men all add to their terror while the point of view allows the viewer a place to take it in. Nothing in the build out and other compositional considerations is its own end and all supports the narrative. A fantastic piece.

As per the fashion drawings of La Gatta verses Erickson and the Potter:

The primary difference is the speed of the lines. When I mentioned relearning how to draw I was referring to drawing out of my head from memory based on anatomy. Such lines have a natural tendency to fluidly as one gains facility with the human figure and this is a quality of the LaGatta images. They lend themselves to speed and of course the form of the body itself, which in his drawings have a tendency to fight the clothing for attention. Some of the clothes were designed to be racy and in that he excelled. La Gatta can at times skirt the edge of daring and such takes a certain warmth out of the image and replaces it with ogling as in the third one titled Milk-Honey.

He is positioning the heads to remove their authority placing emphasis on the clothing and the figure as the other artists do the same. They all removed information from the heads so they lose authority, becoming subordinate to the clothing in as much as a head can.

The speed of the line being more slowly found (in life drawing) in the Erickson and Potter double in function as the type of edges one finds in paintings. The sensitive line is still constructing the figure and clothing but at a slower pace, so the figure is also made subordinate to the clothing and is less overtly sexual. The result is an increased sense of affinity.

In the Picasso a few posts back, his line was so indifferent to form that there was almost no affinity with the figures or their strange shapes. So the Picasso read like text as you put it, without a sense of time, space or affinity.

In the Potter the parts are all supporting the package. Even the marks in the background at right forces itself back on the figure and her gaze out of the picture. It is a well designed image and has overcome much of what you find revolting in photographs.

"In the Picasso a few posts back, his line was so indifferent to form that there was almost no affinity with the figures or their strange shapes. So the Picasso read like text as you put it, without a sense of time, space or affinity." (Sean)

I have to disagree with you on this Sean. Picasso's effects are rarely 'distortions' in the common understanding of the term either for expressive or decorative purposes. He is really applying a sort of fluid or flowing version of cubism that involve continuous changes of scale, proximity and viewpoint. Thinking of his etching you mentioned one is aware, while following the line, of her head being far away, and then, moving down her neck we're getting closer and move under her arm-pit, then our position has flipped to behind her, down to a profile view of a buttock and round again to the front, down a receding leg to a foot seen from the far end of the room etc etc.

In other words Picasso's "sense of time, space or affinity" is constantly changing.

David,

The way you described the era as one of carbon based expressive lines is how it is remembered. An art director I met in 1978 said, I always wanted to be one of those charcoal drawings. My sister said without prompting, I always wanted to be the woman in (Greenhill’s) Lord and Taylor drawings. I bought some old Vogues from 1951 somewhere I can even remember and wasn’t even born when Carl Erickson and Bouche were filling their pages but they bridged the pre war era, war years and post war years accompanying the book and magazine illustrators in the 50s like Fawcett, Briggs and Sickles who for me were also filling pages while I was riding my bicycle. After your comments about the era I went and opened the old Vogues just to see if I was just romanticizing the drawings and I nearly fell over from the smell upon opening one but was quickly reminded why I suffer them. They were great drawings and many superior to the few available online that came largely from the book Fashion Drawings in Vogue published in 1983, author William Packer published by Coward-McCann.

I remember hearing that Potter destroyed a lot of his own work and thought of Walter Everett’s story and then also about how John Fahey published his own solo guitar work beginning in the late fifties and then other solo performances no publisher would touch such as Bola Sete’s remarkable solo guitar work for an album released in 1980 called Ocean and later Fahey’s own interpretations of Sete’s Ocean. Thereafter, Fahey himself lost his creative fire, dying a pauper and yet a bunch of younger solo guitarists have kept this American Primitive/ self taught idea going.

What’s in people that drives them despite all their detractors and so many greats before them I wonder, but when something is good, despite changing times it persists. What can one say about beauty Degas said. I’m sure he was just having a moment of inner amusement at all the talkers. Of course there’s a lot to say, but yes, when something’s good it doesn’t go away.

Reading this site for a long while it strikes me how you and Kev have something in you your other readers share. It’s not a nutty nothing, but it’s a bit nutty just the same. A love of stuff that’s good, even great for being so persistent and for continuing to speak to us.

Chris,

Kyle Stavers, once featured on this blog, spoke in a video about how Picasso blew apart our normal sense of space. He just blew it apart!, she said enthusiastically.

Time is a measure within space and affinity is an intimacy within both.

If space is blown apart and time is blown apart, then doesn’t affinity

get blown apart with it?

What I was referring to was that the lines making up the graphic movements you described in Picasso’s nude model are consistently uniform throughout and indifferent to their surroundings, even flippant compared to the varied lines in the pieces by Erickson and Potter which are sensitive and relational to where they are and the purposes they serve. It's possible Picasso wanted the lines to be superficial in his psychological drama. I wouldn't know. Thanks.

Time is a measure within space

How does this work? This sounds like the "4D world" concept, where the additional dimension is time, but I suspect you mean something else.

Chris,

With respect to your explanation of small and large as foreground and distance I admit that while the turning parts of Picasso's figures read as seeing different points of view as different moments in time, without the overlaps I never read the smaller and larger parts represented in a continuous shape in terms of distance. Thanks for the explanation.

xopxe, If Kyle Stavers said, Picasso blew apart our sense of reality would it have worked? Then time would have been a measure within reality, which is what it is to those who don't believe there is time. It can be hard keeping everyone happy in a world blown apart. No?

It might be fruitful to consider modernist artists like Picasso more as products of their time rather than as singular phenomena. Picasso didn’t blow up time and space, but his approach and works resonated with a zeitgeist of blown up ideals, time and space among them. Cubism is an invented representation of the world just as linear perspective is. And it’s not entirely unlikely that many of the medieval clergy frowned upon that particular distortion of accepted representation of time and space.

The invention of perspective was an attempt to get closer to a sense of reality, not a means of usurping accrued understanding and belief.

What usurped accrued understanding and belief was industrialization and a few reality- warping wars, not the way in which these massive cultural shocks were expressed by people who applied pigmented oil onto canvas.

Chris, don't feed the A.I. Troll account. Otherwise it will continue to make half-sense and you will continue trying to correct it into perpetuity. Don't give it, nor the creep behind it, energy.

(CONTINUED)

I discovered why I think so many artists having tried to emulate the expressive line of Carl Erickson, Bouche and a few others failed so miserably.

Sean

Look closely at LaGatta’s work. I link it here pointedly because it is legitimately loose. All its energetic abstractions – and it is full of graphic life and linear dazzle - are justified with mimetic integrity. His are actual abstractions, and defended as such.

The works of the fellows you posted – like some of what David posted originally - are full of what Harvey Dunn politely identified as “hopeful strokes.” But which we might call Mowattisms (sorry, deep callback).

Dunn said it well when he remarked along the lines of, “You can render it as loosely as you want, so long as you know exactly what it is; its structure.” LaGatta does this in spades. While your examples are so lossy in structure they seem far more speculative than imaginative. Yes the lines are full of variation and specificity. But such only serves to articulate mumbles.

Which is to say, the speed or slowness of the line read – or the speediness or slowness of how a stroke was laid down – does not much matter. What matters is the sensitivity of the artist to relevant information. Sensitivity without meaning – without relevance - is just agitation. And that’s just another version of the random jazzing and jiving of otherwise vacuous lines and fields I’ve been decrying in the hipster illustration ethos that peaked during Kennedy. The legacy of teaching ‘expressive lines’ before actual drawing chops – before actual thinking chops are developed, moreoever – is the proliferation of all manner of form feints - as exhibited in this discussion.

For example, this is a sketch diagram

that exists in fear of concretization. For if it were more fully realized, the fakery would become dogma, and it would sink like a rock. The advertising ellipsis would fill in with leaden fraud and women would turn away. Thus in a sense it is a kite; staying aloft merely by thin framing, light fabric, and wind.

Kev,

The drawings you posted by Lagatta were excellent drawings. I agreed with your original criticism of the pieces kicking off the discussion and loved the one's you posted of Wyeth and Wrightson. I assume you agree with me that the line I was talking about in the Picasso suffers from the artist's lack of affinity with specificity to his subject. His woman could be an interpretation of anyone. I think Sir William Coldspring once said when he first looked at Picasso that its violence frightened him. Not that his first encounter is unique but it is a young artist's first experience not uncommon to lay people.

The point I brought up was that in the drawings of Erickson and Potter, the figure was subordinate to the clothing, which was the subject. Both knew their figures too.

I disagree that the re-posted Erickson was afraid of concretization. Light is washing away a side of the construction in the direction of the woman’s gaze and a directional vector accent at the side of her breast adds emphasis. The construction of the dress on our left side is being slightly opened like an accordion while the figure leans back and on the opposite side where it would fold in is ignored with the empty space serving the back tilting figure. These are deliberate choices which might not be your choices, but the work of Erickson and Potter is not the problem we’ve been discussing. Rather it was teaching shape without any context. Everyone had to take an anatomy class as a foundational course but the classes I described never discussed anatomy and I agreed that this was a serious problem for me and the other students. Finer points weren’t discussed in classes and much of what they did in their professional work was probably as guarded as the way Fuchs or some others guarded their secrets.

Erickson drew for Vogue, a couture magazine for women. The Potter was done for a clothing company catering to women. In Wyeth’s pirates he subordinated some figures to the guy with the blade in his mouth as the primary central look. So there’s a primary moment and secondary, etc. The image isn’t devoured in one gluttonous scoop. It’s dished out in a controlled manner even though it’s a wild scene. In other words, the viewer’s eye is directed, guided, ordered, controlled. Even the build out is subordinated to the central figure as the foreground is in shadow and other heads are partially obscured. I was only pointing out that with multiple heads some are obscured to serve the subject. Likewise in the La Gatta images and that doesn’t rule out secondary motives for doing so. The same thing is happening in the Erickson and Potter where the dress is the star, the primary look and within it movements are being controlled with line variation. You may not think very much of these tools but in their work they certainly thought about them and knew how to use them.

If the re-posted Erickson were a merchandising drawing in a newspaper the client would have demanded more build out as they generally did with tones, buttons, seams and other details. The Vogue drawings aren’t about that, nor was Erickson about hopeful strokes. I doubt very much that comic convention build outs would yield effects as elegant. What I'm saying is that the line variation wasn’t insignificant, without understanding of the figure or desired image, or the outcome of guesswork and ignorance as you seem to be implying.

Sean Farrell-- I have to wonder how much of the renaissance in charcoal and pencil was attributable to the rise of photography. By the 1950s, so much of the magic of realistic images that had once been the exclusive domain of artists had been replicated by photography. The lifetime of labor that went into painting like Bouguereau could be simulated with the click of a shutter, causing many to downgrade Bouguereau's contribution to a variation on Tromp L'Oeil.

Expressive drawing, on the other hand, was a medium better suited for the mid-20th century: it had a directness and simplicity, a spontaneity (or at least the appearance thereof), a rawness and a personal intimacy absent from those labored, overworked salon paintings which were the starting point for much of golden age illustration. Drawing spoke with abbreviation, distilling huge amounts of data into a slender line (and sparing tugboats full of baby linseeds). It assisted in the depiction of modern speed (see, e.g., Bob Peak's racehorse drawing at https://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2012/08/magic-that-believes-itself.html )in a way that salon painting never could.

I raise photography because I'm once again struck by the way photography is an issue in so many of these comments about 1960s illustration. Fine art guiltlessly embraced photography over a century ago; Cezanne, Van Gogh, Degas, Gauguin, Toulouse Lautrec and Eakins were all untroubled by using photo reference. The futurists adapted the blurred look of speed that they learned from film, as did Fuchs. Photography helped develop new vocabularies for art, as artists of good will explored depth of field, multiple successive images, Muybridge-style information and other gifts. Today, demigods of art such as Jeff Koons and Richard Prince no longer make even a minimal pretense of contributing human artistry to their manipulation of photographs.

So why are we few, we happy few, still so troubled by the ghost of photography in some of these pictures? Commenters are troubled by the distortion of the lamp shade in the Fuchs painting, which is the effect of a fish eye lens, deliberately adopted. Some have asserted that "Photographs are just utterly vacuous mentally," or objected that the race cars painted by Daniel Schwartz were "flash frozen" by photography. Others just seem convinced that photo reference is cheating. I can't claim that I'm comfortable with all of the various parameters for the use of photography, but I can't help but feel those fighting a rearguard battle with photography today may miss the anvil of AI dropping on our heads.

Sean Farrell also wrote: "I went and opened the old Vogues just to see if I was just romanticizing the drawings and I nearly fell over from the smell upon opening one"

I can't tell if you consider this a good thing or bad, but for me the olfactory side of old illustrations and comic strips has become a Proustian experience. The evanescence of the paper lends a melancholy touch to the brilliance it hosts. I recently completed a chapter for an international compendium on the history of the magazine in the 20th century; while it has chapters on photography, fiction, art, etc. I could not persuade them to do a chapter on smell.

"when something is good, despite changing times it persists."

Or as Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "Excellence is the new forever." I think much of the art shown on this blog embodies that principle.

". . . the olfactory side of old illustrations and comic strips has become a Proustian experience. The evanescence of the paper lends a melancholy touch to the brilliance it hosts."

Yeah! Shame they wouldn't include such a chapter. The experience of reading comic books (usually Sad Sack or Daredevil or Spidey) in or even the daily newspaper cartoons (Dondi, Judge Parker, BC) in the late 1960's while eating Cheerios still lingers. . .

David,

You’ve offered excellent information and insights why drawing had such a nice run in the 1950s and reflecting on what you said, I think the earlier story of Briggs getting Cosmopolitan to take a chance on his simple drawing in 1951 could have been the spark, just as John Fahey’s nerve to sell publish an album of his acoustic guitar solos set off a new area of recorded music previously dismissed as a waste of time. Art directors played a role, but people with nerve and courage to believe in themselves were the ones who filled the pages.

Upon visiting the website recommended earlier, James Beard’s Unsung Heroes of Illustration, the advantages of drawing form just bounced off the pages. Drawing from imagination or using limited reference progresses so quickly one wonders why it never returned. I think the reason is that many creative people lacked the courage of those who came before them but rather felt the need to follow in their exact footsteps. Bernie Fuchs was a leader, abandoning a style that dazzled the field in his 20s and began a new direction while he was on top the world. When he made that transition, a caravan of people followed him. He kept growing as did Bob Peak and Al Parker before them.

The same can be said of Carl Erickson who was with Vogue for more than 35 years. At Vogue a quick notation with a sense of ease and lightness was the desired look, but Carl Erickson was known to hold his models immobile for agonizing lengths of time. It was a deception and the world was free to dethrone him and Bouche anytime they wanted. Nobody was stopping anyone from doing it, but it just never happened. It’s history now, but the nerve to keep growing remains a rare but necessary quality.

In painting, the rediscovery of form has been at work for a while and narrative is beginning to show up recently in some NY galleries, so I’ve been told. There’s still book illustration and nobody’s stopping illustrators who work with form from illustrating their own books.

The students who were left without a formation and context for drawing form were at a huge loss but who can be blamed for the thousands of aspiring illustrators tracing photos for Workbook ads? So Daniel Schwartz missed an opportunity to make each of his race cars a little different, or stagger them in a more engaging arrangement. All it reflects is that he missed an opportunity, but he kept going. Mistakes can’t be blamed on photographs and neither can remaining stuck in their grasp.

As for the old Vogues, I hadn’t opened them in a long while and wasn’t ready for their distinct odor. Not sure if it’s a positive odor or just a reminder how well the drawings in them have aged.

"Others just seem convinced that photo reference is cheating."

Let’s take care to distinguish 'using photo reference' from 'tracing photo reference' going forward. They are very different issues.

If you accidentally conflate consulting with tracing, you might also accidentally argue against and (of course) defeat the weak argument against using any photo-reference generally (which nobody here makes) and readers might mistake that for you also defeating arguments against tracing.

Furthermore it’s worth distinguishing when whole compositions – figures, elements, props, background, foreground, etc - are traced of a single photo or two, and those where a only a select figure or element or two is traced into an otherwise imagined and hand-drawn composition replete with personal aesthetic decisions.

Lastly, there are two kinds of cheating at play in traced works.

The first is the faking of expertise in perception and drawing ability - a kind of fraud perpetrated on the public.

And secondly there is the cheating of the art of its artistic possibilities by embedding within it and organizing it according to anaesthetic information created by an insensate machine. Which then cheats the audience of richer poetic feeling (in exchange for frozen photographic 'accuracy.')

"Fine art guiltlessly embraced photography over a century ago; Cezanne, Van Gogh, Degas, Gauguin, Toulouse Lautrec and Eakins were all untroubled by using photo reference."

If by ‘Fine Art’ you mean these 6 artists, I think you might be several magnitudes off from a representative sample of the era.

If by 'guiltless' you mean they never mentioned it in public, then yes it was guiltless.

If by ‘embraced’ you mean they sometimes used it, and when they did so it was in order to create work that still looked to be in their own style, rather than photographic in any identifiable sense, then yes they embraced it. (This does not go for Eakins. And why anybody would go for Eakins is beyond me.)

For future reference, you should note that the majority of Degas' photographs date from only the Autumn of 1895. A period when he rarely worked on his art because of his momentary obsession with his camera, which annoyed all his friends of the time. So he probably wasn't a habitual user.

Kev Ferrara-- It seems that when it comes to the marriage of art and photography, everyone is a Goldilocks. Everyone seems to know exactly what's too much, or too little, to suit his or her personal tastes. You are not alone in designating a personal sweet spot somewhere between "using" photos and "tracing" photos that feels right for you. The thing I find interesting is that all this subjectivity-- which should make us humble-- is accompanied by so much fierce indignation and personal shame.

One of the things I like best about this forum is that people here can be pretty tough (like the Illustration Annual judges) about calling out the intellectual gerrymandering that infests the rest of the art world.

Look at all the hypocrisy and subterfuge that accompanies the use of photography. Rockwell was forced to start using photography by his art editors, who wanted him to achieve results he couldn't get by painting models in the studio. He was so humiliated he lied when Oberhardt confronted him at the Society of Illustrators about using photography, and was embarrassed when Leyendecker spied the photographs in Rockwell's studio. Twenty years later, Leyendecker and Oberhardt were both has beens and Rockwell was the most famous illustrator in the world. Robert Fawcett was classically trained to draw at the Slade school and castigated his peers who depended on photographs, yet he had his own personal photographer who discreetly came by to help out. Rodin publicly blasted photography, and yet used photo reference for his illustrations and painted over photos of his nascent sculptures to shape the next steps he wanted to take. Frazetta was another dissembler. These were all brilliant artists, yet they felt the need to disavow photography to keep the magic alive.

Other artists were harder to intimidate. Bernie Fuchs learned to paint highly realistic car ads without photos, but when the benefits of photography were impressed upon him, he openly used photos and was proud of the results. Brangwyn used photos very publicly. Parrish openly used photos. Meltzoff, a classically trained oil painter whose 400 page award winning historical study of painting from Boccaccio to Poliziano (for which he personally translated original source material from Latin and Greek) openly used photographs. Toulouse Lautrec joyfully used photographs, not just for his posters and commercial assignments, but to experiment with visual images with his nude models in his studio.

You too seem emotionally invested in a particular result, which is based on your personal notion of how much photography is acceptable. I gave you a list of seven of the most famous and important artists of the 19th century, and you responded that my list is "several magnitudes off from a representative sample of the era." Would it help if I added Bonnard to the list, who took photos of his wife for his famous bathing series? You push back that Degas only used photography later in his career (which would make sense as photography only became less cumbersome and more accessible late in the 19th century, just as cartoonists such as Stan Drake and Neal Adams began to make more use of photography when the Polaroid camera made it more convenient). But over a decade ago I posted on this blog a couple of Degas paintings that were clearly done directly from photographs (https://illustrationart.blogspot.com/2010/07/from-photograph-to-drawing.html). I would point out that in that same post, I quoted Austin Briggs' discussion about how photography can be helpful and how it can be toxic. Briggs offered, I think, a very thoughtful, sober assessment from a talented, case-hardened veteran.

(CONTINUED)

(CONTINUED FROM ABOVE)